This new biography of pianist Keith Jarrett – the first since Ian Carr’s pioneering effort almost 30 years ago – reached us just as news broke in The New York Times on 21 October this year through an interview with Nate Chinen that the pianist had suffered two strokes in February 2018 and again that May and is unlikely to play in public again. Jarrett’s health has never been that robust: a consistently bad back that made the Köln Concert recording in 1975 such a painful experience, and then a lengthy bout of chronic fatigue syndrome in the late 1990s that drove him from the stage. Such an untimely and unfortunate end to a career of such amazing success, and such single-minded endeavour, gives this biography an unexpected weight and importance.

Its author, Wolfgang Sandner, is the music editor of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung newspaper and a university professor. His biography was originally published in German in 2015, but this edition has been considerably expanded to include not just recent works but also new and substantial information about the Jarrett family itself. Much of this information has been added thanks to the involvement of Chris Jarrett – the youngest of Keith’s four brothers – who as a long-time resident in Germany is proficient enough in German to translate this work into English but is also a pianist, organist and composer with a wide breadth of musical knowledge. Although hard to tell, I suspect that Chris Jarrett’s involvement has been fundamental to the success of this book, although his use of the word “concertized”, as in “these musicians had, until this recording, never concertized together”, is a neologism too far.

In his 2014 acceptance speech at New York’s Lincoln Center (Jarrett segment begins 44:40), at which he was accepted into the circle of NEA Jazz Masters, Jarrett noted that music cannot be described in words: music is nothing but music. Sandner also states that Jarrett’s artistic principles are “meticulous, irritable, nervous and touchy”, all of which sets Sandner a considerable problem, for Jarrett is notoriously silent about what he does, and indeed why he does it. Sandner gets round these roadblocks by a close attention to detail and a clear analysis of recordings.

Following a roughly chronological approach, Sandner starts with Jarrett’s upbringing in unlovely Allentown, Pennsylvania and his early work with Art Blakey, success with Charles Lloyd – an all-acoustic quartet despite appearances to the contrary – and electric stardom with Miles. Importantly he picks up the importance of Jarrett’s first trio with Charlie Haden and Paul Motian, often overlooked by its illustrious Standards successor of Gary Peacock and Jack DeJohnette. But crucially, he also stresses the many different facets Jarrett displayed in his early, largely pre-ECM days. Journalist Robert Palmer raised Jarrett into public consciousness in a triple review in Rolling Stone in 1972 by noting that he had leapt from being “an ex-Miles Davis pianist” to one of the most important piano stylists in jazz at that time. Palmer thought that the American Quartet’s Expectations (CBS) was the album with the widest musical range, while the solo Facing You (ECM) was “without doubt the most the creative and satisfying solo album of the past few years”. He was also complimentary about the quartet’s Birth (Atlantic).

But note the different labels, and also styles. For early Jarrett was spread around three or four labels, and his output was indeed erratic. His first three releases for ECM were the aforementioned Facing You, the piano–drum duet Ruta And Daitya with DeJohnette, and In The Light, a large-scale project with strings, a string quartet, a brass quintet and a jazz combo. This output prompts the question as to which style was Jarrett’s: loud as with Miles, soft when solo, freely improvising at length, adventurous with strings, country in his compositions? Yet while this disparity may hinder understanding of his style, Sandner does point out that these different releases do not make Jarrett a hybrid musician, even less one divided into American and European personalities. They merely reflect Jarrett’s eagerness to put his many and varied ideas into effect. And while he was indeed prolific in his early days – 23 albums under his own name for ECM and Impulse! between 1972 and 1979, plus six more with other bands – Jarrett has in fact been incredibly focused, making only made three (classical) recordings away from ECM since 1978, and never appearing on anyone else’s record since 1980.

Sandner excels in understanding the difference Manfred Eicher makes to recordings, comparing the Impulse! and ECM recordings of the American Quartet to great effect. He is highly informative about the European Quartet with Jan Garbarek and more so about the development of the Standards Trio, noting DeJohnette’s comment that “I get a piano lesson every time we play”. In suggesting that the standards are “a piece of jazz DNA … part of a collective American sub-conscious”, he makes sense of what it is Jarrett sees in such songs. Predictably he devotes a chapter to the Köln Concert, explaining how Jarrett overcame the problems of the concert hall’s piano, and differentiates Jarrett the classical performer from Jarrett the classical composer, noting the failure of Ritual when Dennis Russel Taylor sat on the piano stool and the success of Arbour Zena with Garbarek and Haden.

Where he really hits home is in his lengthy discussions of Jarrett the freely improvising soloist, most of whose solo recordings have minimal or no sleeve notes to help listeners understand the music. Sandner argues that these recordings are the very essence of who Jarrett is, an essential loner whose solo recordings have made him unique in modern-day jazz. The Bremen/Lausanne live set of 1973 broke with a long-standing jazz tradition by dispensing with pre-existing head arrangements as springboards for improvisation. Indeed, except for concert encores and two discrete sets – notably The Melody At Night, With You – Jarrett never resorted to any written material again when playing solo. Jarrett himself has said that: “If I could call everything I did Hymn, it would be most appropriate, because that’s what they are when they are correct.” Sandner defines what Jarrett plays as “improvisations using tools but no material, free solistic piano-playing without an outline, and developed out of momentary inspiration”. Created as they all are in the vigour of the moment, the solo works, says Sandner, are an extraordinary cumulative and cultural achievement. Interestingly he praises the usually overlooked Staircase set recorded in Paris in 1976 as one of the finest, commenting unfavourably on the bizarre double LP Invocations/The Moth And The Flame, and lauding the massive Sun Bear set of 1979 for the sheer inexhaustible fantasy that it is.

He is particularly astute when referring to the coughs and camera flashes that can disrupt a solo performance: is Jarrett’s refusal to continue until there is silence merely an attempt to cover up his lack of ideas, to give himself another chance? Sandner is not so cynical, preferring to accept that his occasional tirades “remain marginal phenomena which have no effect on the music itself”. But he does suggest that Jarrett sees the piano as his opponent, an instrument to be subjugated. When the barriers are broken down, then the music really flows.

Throughout, Sandner surprises by his observations, correctly noting that after his halt due to chronic fatigue syndrome in the late 1990s, Jarrett – contrary to what one might expect from a still ill man – never again resorted to the safety and comfort of the studio, excepting a duo session with Haden that produced two albums and a set of Bach sonatas for violin and piano. Every solo and trio album since 1999 has been recorded live. Indeed, Jarrett’s only concession to frailty was that the lengthy solo excursions of old that once occupied an entire album were now replaced by a series of shorter, more succinct displays.

This is a musical biography to enjoy and think about, to read and then be returned to the records informed with new insight. As befits its reticent subject, it is not a personal biography of the pianist, although the necessary details are here, but what it does so well is to explain why Keith Jarrett is so important, and why his two strokes – the news of which came just after this book went to the press, although the post-2018 silence is noted with concern – have probably ended the career of a musical genius. If that proves to be the case, this is the biography that will help us make sense of his remarkable legacy.

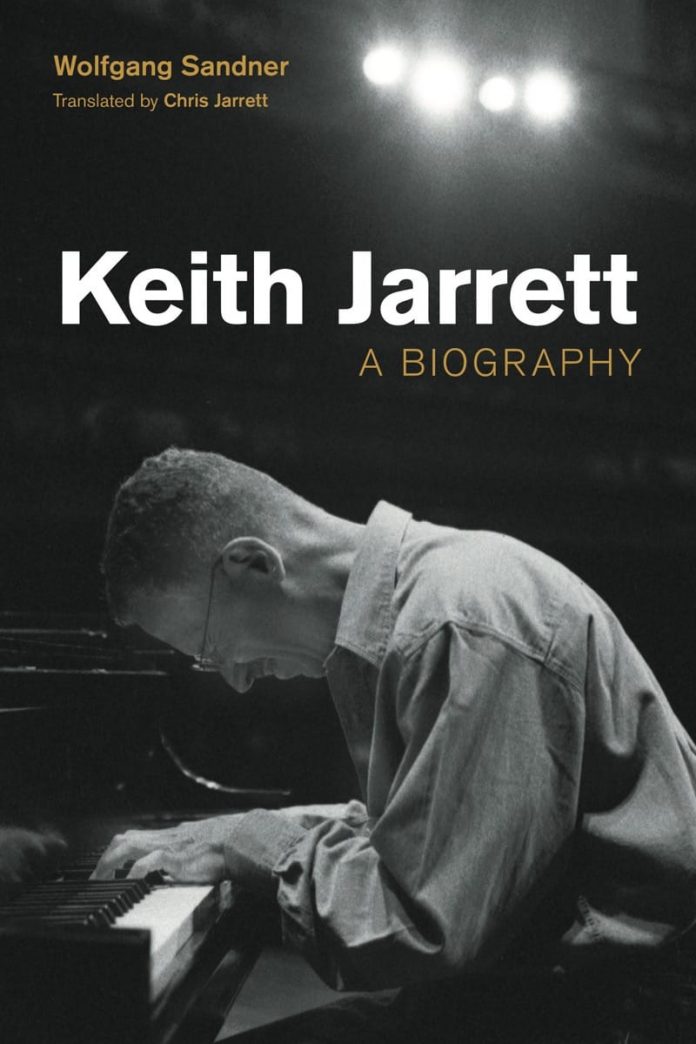

Keith Jarrett: A Biography by Wolfgang Sandner, trans. Chris Jarrett. Equinox, hb and eBook, 228pp, 26 b/w photos, discography, bibliography. £25. ISBN 9781800500112