It’s common to associate early jazz with what might be considered low life and immorality, or something more than vaguely disreputable, despite efforts to sanitise it as a means of raising its status and spreading its message.

The music in those days was replete with “dirty” songs and attempts to clean them up. The word “funk” originally meant the smell of unwashed human genitalia, post-coital: “Man, you could cut the funk in there!” A filthy, non-bowdlerised song did not beat about the bush, as it were, with euphemism and innuendo: it was delivered full monty honky-tonk.

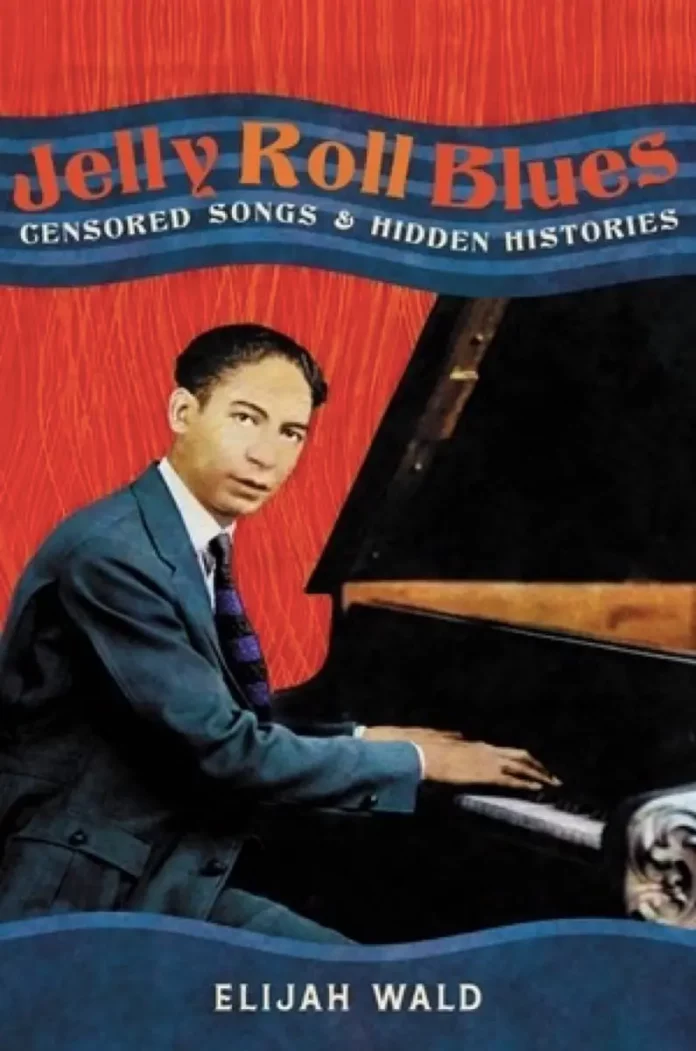

That’s the subject matter explored in Elijah Wald’s excellent book – and some. If pre-phonographic, it largely remains buried for want of investigation, though there have been any number of investigators, notably in the US Alan Lomax and his father, John. Recording for commercial purposes demanded self-censorship and circumspection from musicians and informants – and, indeed, from and for some investigators themselves, mostly but not exclusively white, reputable and middle-class.

Morton is both at the heart of the book and also running through it. His 1938 Library of Congress recordings for Lomax junior included a 30-minute 12-bar blues called The Murder Ballad that took up seven sides of four 78rpm shellacs. Morton, if not the sui generis inventor of jazz, was in the mix if not central to its formal beginnings and development, playing over a century ago in dives in New Orleans and in Gulf Coast states. Fewer than 20 years later, he was in Chicago and New York, creating some of the finest small-group jazz ever recorded. But the diamond embedded in his front teeth flashed with the mark of a successful pimp.

New Orleans jazz was born in the Red Light districts of that city. The one known to posterity but not to anyone who worked there – prostitutes and musicians – was Storyville, which served white punters. Another district uptown catered for a racially mixed clientele and was where the blues and what the author calls “rougher jazz styles” flourished. (To this day, the realities of millennial New Orleans at that time are obscured for visitors by myth and positive PR. It was never all Mardi Gras. The city was literally dirty, one of the last big urban areas in the US to get a sewerage system; clean running water was guaranteed only as late as 1909.)

Wald’s book suggests that uncensored blues lyrics were pretty much universal among those for whom they were the norm and a spade was not called a spade but a fucking spade. Lewdness was the lingua franca, repulsive only to those beyond its yell. Even Morton couldn’t bring himself to repeat some of the lyrics to Lomax; and, as Wald points out, the words were not only obscene (a loaded, pejorative term) but often racist and misogynistic. Early on, he issues a caveat lector.

But early on, too, the reader is keen to concentrate not so much on the censored songs of the title but the histories and characters hidden behind them. Oft repeated, crude language just becomes boring. That said, there are lessons to be learned, even about lexicons of the uncouth. For example, “pimp” for black Harlem urbanites meant not a procurer but a sort of male gigolo seeking a woman to keep him – and her – supplied. Even euphemism could verge on the unprintable: in 1934 the Bangor Daily News appealed for discarded lyrics, to which a lumberman, possibly with tongue in cheek, responded thus:

Like the robin and the thrush,

Keep your head beneath the brush,

And your hand upon your little ball of yarn.

The vanished histories and the colourful men and women behind them flow from Wald in eloquent spate. W.C. Handy’s band performed in the Red Light area of Clarksdale, Mississippi before white audiences while respectable black families walked past the “latticed houses of prostitution” on their way to church; square-dance callers would shout vulgar directions (“vulgar” doesn’t really cut it); and Frankie “Half Pint” Jackson sang How Long Blues in a feminine falsetto while faking an elaborate orgasm.

Women were the dominant blues audience from the start, despite their representation in many lyrics as less than men’s equal in matters of sexual congress. A final examination of The Murder Ballad finds Wald making the point that Morton’s story is told mostly in the words of the female protagonist and foresaw a time “when a woman won’t need a man”; this was in contrast to the sentiment of “Stavin’ Chain” – a moniker adopted by several musicians as a paradigm of the black man who can wrongfoot his white counterpart in everything, including sex – that portrayed the opposite gender as expendable. The individual, male or female, was deemed to be be self-sufficient in sex.

Wald’s book, with its commendable 49 pages of annotation, bibliography, and index, is crammed with insight and exegesis of famous blues charts and their moveable lyrics, no less than with portraits of the famous, infamous and obscure characters associated with them. Exposition of the crude and, to some, unspeakable, coupled with the lifestyles it reflected, offers the reader jazz as refreshing musico-social history from the perspective of the bawdy, the earthy and the racially complex.

Jelly Roll Blues: Censored Songs & Hidden Histories, by Elijah Wald. Hachette UK, 336pp, pb, £28, ISBN (hardcover) 9780306831409; (e-book 9780306831423)