‘Manfred Eicher and ECM have given invaluable opportunities for fresh musical ideas and experiences of lasting quality to reach listeners world-wide. What they have done over the past decades is truly remarkable’ – Bobo Stenson

The history of recorded jazz runs back just over a century. It’s quite a shock to realise that ECM (Edition of Contemporary Music) has been around for practically half that time. Founded in 1969 by Manfred Eicher – a classically trained but improvising double-bassist, and a sometime production assistant for Deutsche Grammophon who had developed an enthusiasm for modern and avant-garde jazz – the label’s durability has something of a saga-like aura to it. Today, the quality of the world-ranging ECM catalogue speaks volumes for the Munich-based company. This year ECM celebrated some of its back list with the release of 50 items in the mid-price Touchstones series. I reviewed the first half of these in a 21 April post which I’m happy to note is currently not all that far short of three thousand hits.

In an ever-more corporate and globalised world, ECM has remained a small-staffed and intensely committed enterprise, retaining its essential independence of means and manner. It has long been a byword for integrity, an inspiring integrity of open-minded creative musical conception and overall clarity (or transparency) of recorded sound. From the start – the November 1969 recording and January 1970 release of pianist Mal Waldron’s Free At Last with Isla Eckinger (b) and Clarence Becton (d), which is reissued this month with new material in a two-LP format – all such musical matters have been enhanced (in both LP and CD format) by what many consider the most thoughtful and aesthetically stimulating visual packaging ever given any recorded music.

This side of ECM is profiled in two sumptuous volumes: Sleeves of Desire (1996) and Windfall Light: The Visual Language Of ECM (2010), both from the distinguished publishing house of Lars Müller; and it is examined further in the 2012 Haus der Kunst/Prestel Verlag publication ECM: A Cultural Archeology – which includes an ECM discography from 1969 to 2012. There have also been excellent ECM releases on DVD, some featuring concert performances, e.g., from Keith Jarrett’s Standards Trio, and others placing such performances in broader cultural context, such as in studies of the work of John Abercrombie, Charles Lloyd and Marc Sinan and the collaborative ventures of Dino Saluzzi and Anja Lechner – the last including some fascinating passages of Saluzzi and George Gruntz performing together.

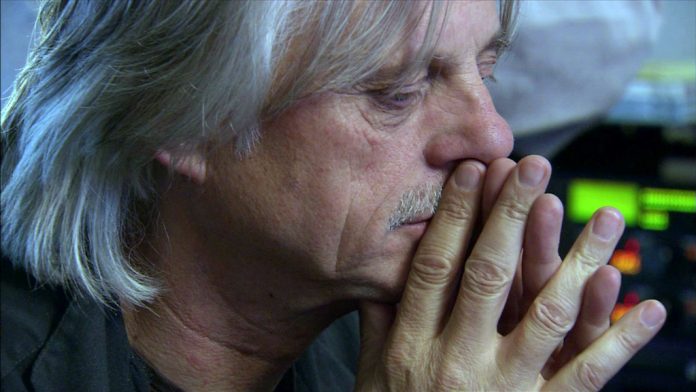

Manfred Eicher: ‘…an extraordinary feeling for silence, for rhythm, for the tone colour of instruments’

And having released earlier the complete soundtracks of Jean-Luc Godard’s Nouvelle Vague and Histoire(s) Du Cinéma, ECM launched ECM Cinema in 2006 with Four Short Films by Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville. These included Liberté Et Patrie (2002), which among other things, is a penetrating study of the growth of the artistic or poetic imagination and one of Godard’s finest latter-day achievements. 2011 saw the release of Peter Guyer’s and Norbert Wiedmer’s Sounds And Silence: Travels With Manfred Eicher. Here, Eleni Karaindrou – the Greek composer and pianist whose work for the label has involved collaborations with Jan Garbarek on Music For Films (1986/90) and Concert In Athens (2010, for ECM New Series) – spoke of her complete trust in Eicher: “Manfred cannot be fitted into any category. He is a producer, composer, musician, rolled into one, but a poet too. With an extraordinary feeling for silence, for rhythm, for the tone colour of instruments. And wherever he may be, he is totally committed. This is the quintessence of a passion”.

Manfred Eicher was born in 1943 in the medieval town of Lindau on the shores of Lake Constance and graduated from Berlin’s Musikhochshule in 1967. In an extensive and informative interview with Stéphane Olivier, published in France’s Jazz Magazine in May 2017, Eicher spoke of his evident European background, of his affinity for European literature, pictorial art and cinema, and of how he had long been nourished by Bach and the string quartets of Beethoven and Schubert, for example. But he spoke also of his life-long curiosity about other cultures and cultural spheres and of how he had always been fascinated by America.

Contemporary American jazz in particular inspired the young Eicher, from Lee Konitz and Gil Evans to Miles Davis’s Kind Of Blue and Albert Ayler’s Spiritual Unity. The trios of Bill Evans (with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian), Paul Bley and Jimmy Giuffre were of special interest, together with The Art Ensemble of Chicago. As a teenager, Eicher hitch-hiked to Munich to hear the classic Coltrane Quartet and later would play on occasion with musicians of quality such as Marion Brown. His free-ranging yet lyrical pizzicato improvisations, very much in the post-LaFaro vein, can be heard on pianist Bob Degen’s May 1968 Calig trio recording Celebrations, with African-American drummer Fred Braceful.

However, it was production rather than playing which Eicher quickly came to feel was his true vocation. Laying aside his double bass, he supervised for Calig the extraordinary, in good part Dada-fired Wolfgang Dauner – Eberhard Weber – Jürgen Karl – Fred Braceful. Bearing the legend “Produced by Manfred Eicher + Jazz By Post”, this is a session which, like all the early ECM dates which followed, should be required listening for anyone mistaken enough to think that Eicher began his career as an independent producer recording classical string quartets.

ECM was founded at the end of a decade of tumultuous avant-garde activity, much of it centred on free jazz. And free jazz, or free improvisation, has long featured at ECM – as Derek Bailey’s early presence on the label attests, together with the later recordings of, for example, The Art Ensemble of Chicago, Evan Parker, Joe Maneri, The Berlin Contemporary Jazz Orchestra and Alexander von Schlippenbach’s Globe Unity Orchestra (the last released on ECM’s sister JAPO label). Some of the most remarkable sessions on ECM, such as Roscoe Mitchell’s two-CD Bells For The South Side (2015) – which was produced by Steve Lake, a key veteran of the ECM team who besides his work in production has written many an illuminating sleeve-essay for the label – testify to the lasting influence of free music: free music conceived, not so much as a genre of particular parameters, but rather as an invitation to approach and develop the potentialities of musical expression in the broadest, deepest and most cliché-free manner.

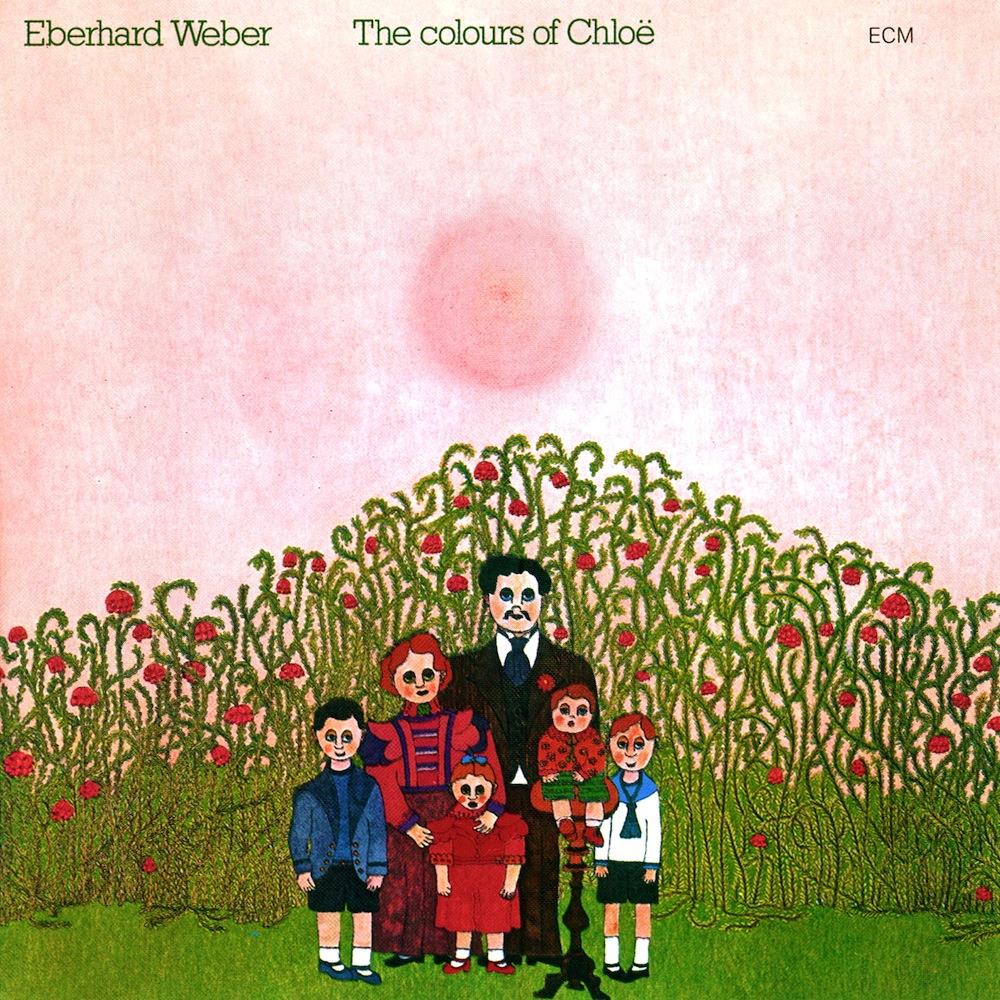

The overall freedom of conception and expression which distinguishes the ECM label has always eschewed the dogmatism of those whose enthusiasm for free music can render them deaf to the lyrical melodies and nuanced harmonies, the compositional character and freshly cast grooves, which distinguish such seminal early ECM releases as Eberhard Weber’s The Colours Of Chloë (1973) and Keith Jarrett’s Köln Concert and Belonging (both 1974) – the former the famous solo live concert recording released originally on two LPs and the latter featuring the pianist’s Nordic quartet with Jan Garbarek, Palle Danielsson and Jon Christensen.

Acknowledging that ECM is not always to everyone’s taste – chiding critics have spoken of “Easy Children’s Music” or “Excessively Cerebral Moods” – Marshall maintains that “Whatever anyone thinks of the music, no-one can deny what a force ECM has been”

The British drummer John Marshall, long known for his work in Soft Machine – which this year celebrates its own 50th anniversary, in common with the AEC – has recorded for ECM in a range of innovative contexts featuring such distinctive improvisers as John Surman, Charlie Mariano, Eberhard Weber, Arild Andersen and Vassilis Tsabropoulos. Acknowledging that ECM is not always to everyone’s taste – chiding critics have spoken of “Easy Children’s Music” or “Excessively Cerebral Moods” – Marshall maintains that “Whatever anyone thinks of the music, no-one can deny what a force ECM has been – and continues to be. And not just in jazz and free or purely improvised music, but also in various fields of folk-inflected composition and improvisation – plus, since the New Series side of the label started in the early 1980s, the classical field, including both early music and contemporary minimalism, as well as poetry, film and theatre. It may have been Sun Ra who said ‘space is the place’ but it’s at ECM that space has really come into its own. And this is largely thanks to Manfred’s particular way, his determination always to get to the essence of things”.

In the sleeve-note to his recent Mack Avenue release Take Another Look: A Career Retrospective, Gary Burton reveals that he came of age as an artist during his time at ECM. In a January 1979 interview for Downbeat Burton challenged the recently emergent critical canard – which referenced recordings such as Pat Metheny’s Watercolors (1977) – that ECM had become a laid-back, one-mood affair. The surpassing vibraphonist – who supplied a sleeve encomium for Metheny’s Bright Size Life (1975) with Jaco Pastorius and Bob Moses, and whose own gems for the label include Crystal Silence (1972) with Chick Corea, Seven Songs For Quartet And Chamber Orchestra: The Music Of Mike Gibbs (1973) and Slide Show (1984) with Ralph Towner – underlined the jazz-fuelled breadth of Eicher’s activities, including recent work with the AEC. Brian Morton’s 24 March post this year spoke of the “embarrassment of riches” that is the 18-CD box set The Art Ensemble Of Chicago And Associated Ensembles (1978-2015) which documents the work on Nice Guys (1978) alluded to by Burton, together with subsequent related recordings by ECM.

In the aforementioned 2017 Jazz Magazine interview with Stéphane Olivier, Eicher responded to any possible charge today of there being a reductive uniformity of sonic conception or identity at ECM by pointing to the range of locations and studio engineers underpinning the overall diversity of the label’s work: “Forget the clichés, listen to the music!” And what music there is to hear, to reward requisite attention.

One thinks, for example, of the diversely exploratory solo recordings of Keith Jarrett and Paul Bley, Chick Corea and Ralph Towner; Dino Saluzzi and Eberhard Weber, David Darling and Barre Phillips, Björn Meyer and Larry Grenadier; of the characterful duo sessions from Gary Burton and either Corea or Towner, as well as from Towner and either John Abercrombie or Paolo Fresu, and also from Jan Garbarek and Art Lande, Egberto Gismonti and Nana Vasconcelos, Fresu and Daniel di Bonaventura, Gianluigi Trovesi and Gianni Coscia; of John Surman’s superb series of solo recordings, from Upon Reflection (1979) to Saltash Bells (2009); of the myriad ways in which ECM has helped sustain and stimulate the development of piano trio jazz, whether European, Scandinavian or American, or worldwide, while also documenting a potent expansion of the potentialities of the electric jazz guitar. Think of a relatively unsung masterpiece like Mick Goodrick’s In Pas(s)ing (1978) with a.o John Surman – and of the diverse sound-worlds of Terje Rypdal, Pat Metheny, John Abercrombie, Bill Frisell, David Torn, Eivind Aarset, Raoul Björkenheim, Christian Fennesz and Jakob Bro.

And then there is ECM’s radically fresh approach to matters of genre and repertoire, composition and improvisation, instrumentation and voicings: witness Keith Jarrett’s In The Light (1973) with a.o. The American Brass Quintet, Arbour Zena (1975) with Jan Garbarek, Charlie Haden and a string section drawn from the Radio Symphony Orchestra, Stuttgart, and the solo Hymns Spheres (1976) on baroque organ; Wadada Leo Smith’s Divine Love (1978) with a.o. Dwight Andrews, Bobby Naughton and Lester Bowie; Eberhard Weber’s Fluid Rustle (1979) with Bonnie Herman, Norma Winstone, Gary Burton and Bill Frisell; Azimuth’s John Taylor, Norma Winstone and Kenny Wheeler and their Azimuth/Touchstone/Départ (1977/78/79, with Ralph Towner present in part), Azimuth ’85 and “How it was then … never again” (1994); Pierre Favre’s Window Steps (1995) with a.o. David Darling and Steve Swallow; Dino Saluzzi and The Rosamunde Quartet’s Kultrum (1998); John Potter and The Dowland Project’s In Darkness Let Me Dwell (1999) with John Surman and Stephen Stubbs, and Care-charming Sleep (2003) with Surman and Stubbs, Maya Homburger and Barry Guy; Jan Garbarek’s In Praise Of Dreams (2003) with Kim Kashkashian and Manu Katché; Paolo Fresu’s Mistico Mediterraneo (2010) with Daniel di Bonaventura and A Filetta Corsican Voices, Athens Concert (2010) by Charles Lloyd and Maria Farantouri with a.o. Jason Moran and Sokratis Sinopoulos, and the three “meta-music” recordings by Eberhard Weber, such as Hommage (2015) with a.o. Jan Garbarek, Paul McCandless, Gary Burton and Pat Metheny, which followed the stroke of 2007 that ended Weber’s playing career.

To be continued

N.B. Except where noted, all dates of albums signify the date of recording, not issue.

This article is an amended and expanded version of a piece which was commissioned by Magnus Nygren of Sweden’s JAZZ ORKESTER JOURNALEN and published there in edition nr. 5, November-December 2019. It appears in Jazz Journal by kind permission of JAZZ ORKESTER JOURNALEN