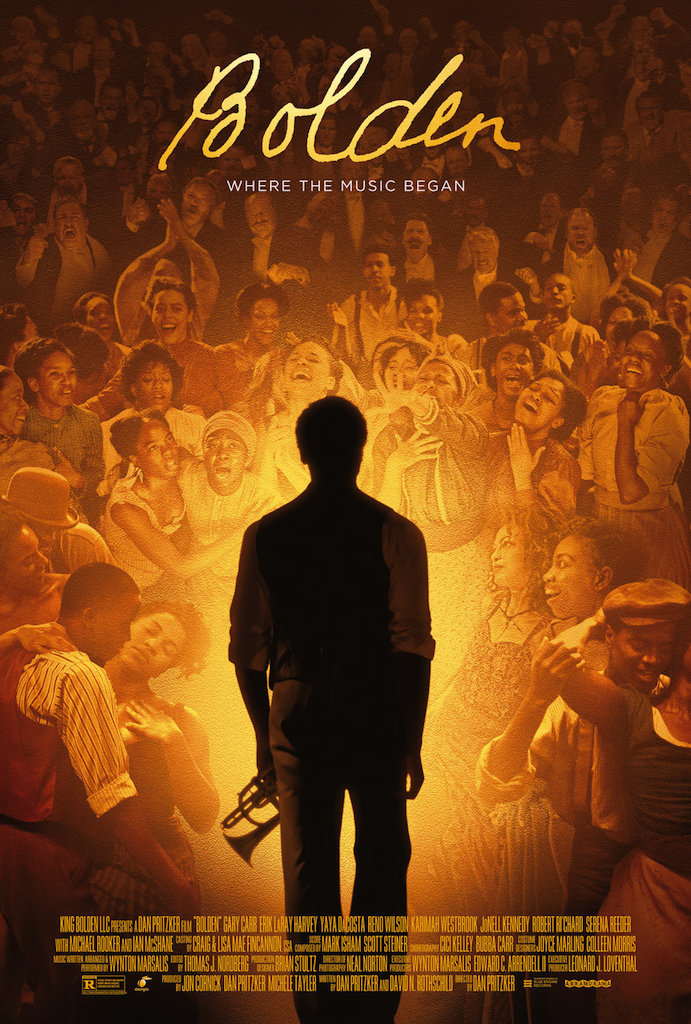

I learned everything I know about Buddy Bolden from Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya, the one indispensable book about jazz from soup to nuts, co-edited by Nat Hentoff and Nat Shapiro and published in 1955. A new film, Bolden, written, produced and directed by Dan Pritzker and released in the US in May 2019, added precisely nothing to what I gleaned from HMTTY, for the fact remains that precious little is known about Bolden. This makes the film more an impression of a black cornet player born in New Orleans in the 19th century. That was where Bolden was active from around 1895, achieving both fame and respect before being committed to the Louisiana State Asylum where he died in November, 1931.

Although yet to be released in the UK, there are 14 reviews on IMDB, presumably from US movie buffs, and they range widely across a gamut running from “brilliant” to “crap”. Having now watched it myself I can “see” both points of view. That it is confusing is indisputable – in fact I watched it twice in the space of 24 hours and still didn’t know who Ian McShane was supposed to be playing, for all I knew it could have been Lovejoy’s grandfather but the end credits revealed he was in fact playing a judge.

I won’t pretend that it’s an easy watch because it’s shot in short takes rather than long, fluid takes, virtually exclusively from the point of view of a schizophrenic mind recalling a life in random short bursts with no concession to chronology. But it is fascinating, especially for anyone with an interest in the Crescent city as it gave birth to jazz

For a film built around a musician who was part of a thriving musical community in a city universally acknowledged as the birthplace of jazz, director Dan Pritzek keeps us waiting a good three to four minutes for the initial downbeat. There are no opening credits and the first thing we see is three simple, declarative sentences in white script on a black background: Very little is known about Buddy Bolden. He was born in New Orleans in 1877. He invented jazz.

The first two are factual, the third is opinion masquerading as fact. The film proper begins with a series of abstract images culminating in a woman in the uniform of a nurse tuning a radio to a station featuring a broadcast by Louis Armstrong and his orchestra. We get only a few frames before cutting to a man listening to the broadcast and then vice versa. In an effort to save time and simplify I’ll put you in the picture. Bolden was admitted to the Louisiana State Asylum where he died in November 1931, some four months after the broadcast by Armstrong so everything that follows emanates from Bolden’s sick mind remembering incidents from his life in random order. It’s not unlike a visualisation of the streams-of-consciousness in William Faulkner’s The Sound And The Fury.

There is very little dialogue anywhere, which means we are obliged to guess at what is happening. Sometimes it’s relatively obvious – the scenes in the factory where women are working as a young boy curls up under a bench clearly show an infant Bolden watching his mother in her place of work – and sometimes virtually impossible to decipher – the scenes of boxers fighting both in and out of the ring could be anything. Bolden was known as a womaniser who was virtually irresistible to women and the several scenes showing Bolden coupling with various women may well be there to ensure the dirty raincoat brigade help the producers get the neg cost back.

But first and foremost Bolden was a gifted musician who quickly became known as “King” Buddy Bolden. Wynton Marsalis, who is credited with writing, arranging and playing the score, has done an excellent job of writing new material that replicates accurately the both the sound and the style of the beginning of what was known originally as “jass” and very soon became jazz. If we turn to the book Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya we read the only direct testimony available, what historians call primary source. Mutt Carey says: “When you come right down to it the man who started the big noise in jazz was Buddy Bolden. Yes, he was a powerful trumpet player and a good one too. I guess he deserves credit for starting it all”. Bunk Johnson says: “King Buddy Bolden was the first man that began playing jazz in the city of New Orleans … now that was all you could hear in New Orleans, that King Buddy Bolden’s band and I was with him. That was between 1895 and 1896”. Kid Ory says: “I used to hear Bolden play every chance I got”. Louis Armstrong says: “He was just a one-man genius that was ahead of ’em all … too good for his time”.

After (presumably) reading this kind of testimony Pritzik began to fashion Bolden (11 years in the making). I won’t pretend that it’s an easy watch because it’s shot in short takes rather than long, fluid takes, virtually exclusively from the point of view of a schizophrenic mind recalling a life in random short bursts with no concession to chronology. But it is fascinating, especially for anyone with an interest in the Crescent city as it gave birth to jazz. Bolden is played about as well as he could be by the English actor Gary Carr who appeared in Downton Abbey but is arguably better known as Fidel in Death In Paradise, and Reno Wilson contributes one of the best zeroxes of Louis Armstrong you’re ever likely to see, capturing not only the voice but also every mannerism from the eye-rolling onwards. Throw in the score in which Wynton Marsalis recreates the sound of New Orleans circa 1900 to a fare-thee-well and we’re talking very singular movie.