Lady Day (1915-1959) has had many biographers including Donald Clark, Wishing On The Moon (1994), Stuart Nicholson, Billie Holiday (1995), David Margolick, Strange Fruit: The Biography Of A Song 2001, Leslie Gourse, The Billie Holiday Companion: Seven Decades Of Commentary (1997), Julie Blackburn, With Billie (2005), Farah Jasmine Griffin If You Can’t Be Free, Be A Mystery: In Search Of Billie Holiday (2001), and John Szwed Billie Holiday: The Musician And The Myth (2015). Mention should also be made of Ken Vail’s Lady Day’s Diary: The Life Of Billie Holiday 1937-1959 (1996). With a wealth of photographs, press reportage and details of her club and record engagements over 40 years, together with Vail’s own succinct prose, it covers her last decade in an exemplary manner.

Now Paul Alexander, biographer of J.D. Salinger and Sylvia Plath, has compiled a highly detailed examination of Billie’s final year. But his book, although well-intentioned, is too long and discursive (353 pages), while the copious (293) footnotes are not numbered in the text and have to be laboriously worked out by identifying fragmentary quotations in “Notes” (38 pages) at the end of the book. Strangely, there is no bibliography – although there are four closely spaced pages of “Acknowledgements”. Neither is there an Introduction – where was the editor?

The 15 brief chapters ostensibly cover the months May 1959 to “July 1959 and Afterwards”, but Alexander fails to stick to this chronological order by ranging back and forward in time over her life. He describes (in detail) Billie’s public performances (in the United States and Europe) during the last months of her life. These were either amazingly moving or barely audible. Alexander indulges in far too many speculative assertions about her feelings. One example can suffice for many: “Her years of performing with Basie and [Artie] Shaw, then at Café Society, were far from her thoughts on [the] evening in July 1958 as she sat in the back seat of a private car on her way to Newark.”

She was going to Newark to appear on WNEW’s radio show Art Ford’s Jazz Party. Her accompanists included Mal Waldron, Osie Johnson, Tyree Glenn and Georgie Auld, and her songs included some from Lady In Satin. Alexander reports that Ford was delighted with Billie’s performance and said “If everything is all right with Billie Holiday, everything is all right with jazz.”

The concluding chapters cover Billie’s relationships with Lester Young and pianist Mal Waldron, her final incarceration on trumped-up drug charges by the “authorities” – including the FBI and J. Edgar Hoover – and a harrowing account of her rapidly deteriorating health and last days. Earlier there are reminders of her affairs with (among others) Orson Welles, Roy Eldridge, Joe Guy and (sensationally) Tallulah Bankhead. Her disastrous marriage to the conniving and violent Louis McKay receives deserved attention but there is little here that will surprise Holiday devotees.

There are also numerous mentions of her most infamous song, Strange Fruit, which was an indictment of the lynchings of African-Americans in the Deep South in the 1930s and 40s. Alexander correctly calls it “a masterpiece of longing and sorrow [which] was an early catalyst that contributed to the growing civic consciousness” that was to ignite the civil rights movement in the mid-1950s. More questionably, he applauds her penultimate recording – Lady In Satin – as reflecting the “suffering, the heartbreak” in “the damaged tortured voice captured on the album, heightened by [Ray] Ellis’s rich orchestral music”. Many critics would question this judgment.

Alexander is on firmer ground when he asserts that “during the 1950s, a decade defined by conservatism in the multiple forms of sexism, racism, and homophobia, Billie Holiday was devalued as a woman and minimalized as a singer and musician”.

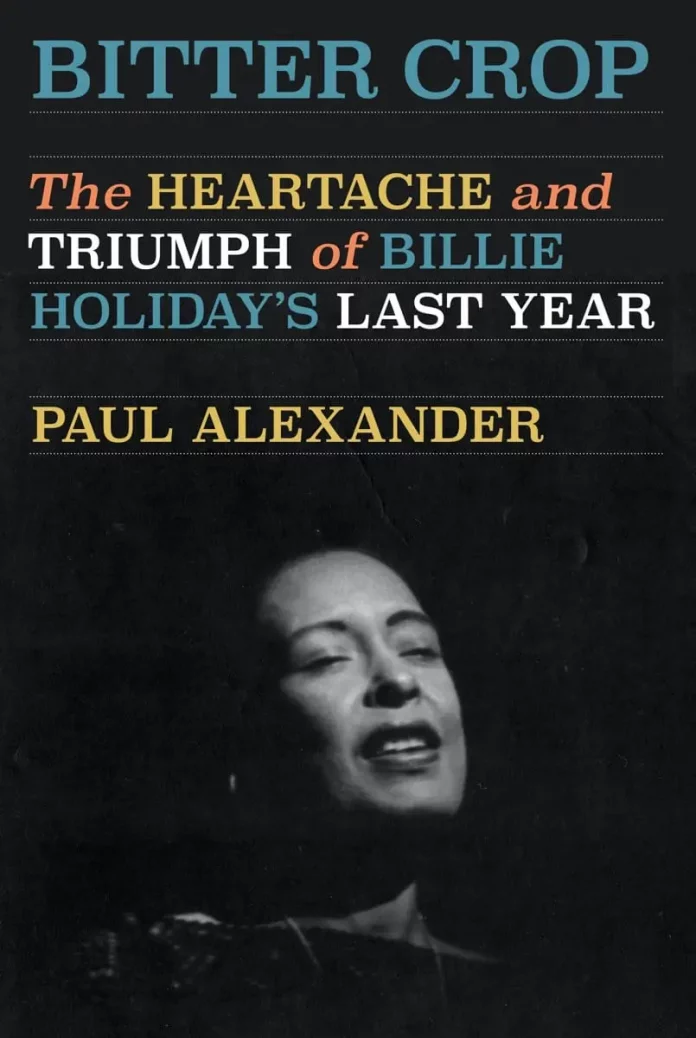

Bitter Crop: The Heartache And Triumph Of Billie Holiday’s Last Year, by Paul Alexander. Alfred A. Knopf. New York, 2024; 353pp; hb. ISBN 9780593315903