Gretchen L. Carlson is a musicologist and a professor of music at Towson University, USA. Sympathetic to what have become known as The New Jazz Studies – which tend to privilege the materialist and structural concerns of social history and sociology over the individualistic or style-based approaches of old – Carlson likes to “theorize” matters, drawing upon ethnography and sociology as well as music and film analysis. She speaks of “the essentiality of directorial investment”; of jazz’s “sonic signifiers” and “listenership”; of “technologies, modalities and cultural ideologies”. And she is especially interested in jazz’s shifting relation(s) to “popular culture”.

The summarising illustrative subject here is the jazz-inflected film scores (all by males) of a select number of American cinema releases from the late 1970s to now, treated midway-to-late in the text and set in the context of a welcome but partial background historical overview of the interplay of jazz and film. One indication of how partial this overview is is the fact that there is no mention of ECM. For over 50 years, the label has refreshed and refigured improvised jazz poetics, with a filmic sensibility often in the mix. Hear, for example, Eleni Karaindrou’s Music For Films (1991) or see Heinz Bütler and ECM director Manfred Eicher’s Holozän (1992) which includes music by, a.o., Jan Garbarek and Keith Jarrett.

Improvising The Score sets out its stall in America as Carlson outlines the opening sequences of Otto Preminger’s Anatomy Of A Murder (1959) with its Duke Ellington score. But Europe soon enters the picture – and once it does, I feel that Carlson should have committed herself to outlining as wide a cultural/geographical background as possible. After all, jazz and film have long been world-wide phenomena.

British film is absent as are two of the finest jazz film scores of the early 1960s: Giorgio Gaslini’s music for Antonioni’s The Night (1961) and Krzysztof Komeda’s work on Polanski’s Knife In The Water (1962). However, Carlson is keenly aware of the overall “golden era” of jazz soundtracks: the 1950s and 1960s, which saw the success of French New Wave films such as Louis Malle’s Lift To The Scaffold (with its improvised score by Miles Davis and a Euro-American quartet) and Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (scored by Martial Solal) as well as further jazz scores from artists such as Duke Jordan and Thelonious Monk, Quincy Jones, John Lewis and Charles Mingus.

Carlson regrets what she sees as the subsequent dearth of jazz-inflected film scores and the lessening of jazz’s importance in and for popular culture. She ignores Julian Temple’s Absolute Beginners (1986) with its score by Gil Evans – a British film one might have thought relevant to her concerns – but touches on Bertrand Tavernier’s 1986 Round Midnight (scored by Herbie Hancock), Clint Eastwood’s 1988 Bird (scored by Lennie Niehaus) and – in the footnotes – Robert Altman’s Kansas City (1996). The later Whiplash (2014) and La La Land (2016) by Damien Chazell and Don Cheadle’s Miles Ahead (2016) also receive brief attention, while more recent releases like George C. Wolfe’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020), Disney-Pixar’s animated feature Soul (2020) and Lee Daniels’s The United States vs. Billie Holiday (2021) are name-checked.

What, then, is Carlson’s take on jazz?

Improvisation, she says, is – “ perhaps” – jazz’s defining feature (p 20). Well, is it or isn’t it? How about all those blue notes, or harmonic literacy; syncopation, swing and groove – as well as the factor of unpredictability? Some improvisation can be tediously predictable. Carlson certainly values the “risk factor” at the heart of jazz, which has long posed a major challenge to the “gatekeepers” of conventional film scoring, editing and production. Looking for a “proliferation of risk discourse in film”, she would like to see more “maverick directors” able to foreground jazz’s contributions to a completely integrated film dynamic. But what this might mean for matters of spatial and narrative interplay in film needed more of the sort of treatment which is only hinted at in the brief consideration of the temporal dislocations of Cheadle’s Miles Ahead (pp 147 & 171). I’m surprised that, given the radical nature of her ideas, Carlson does not mention the long-famous range of cinematic techniques explored in Dziga Vertov’s Ukrainian-Soviet silent-film classic Man With A Movie Camera (1929). The Canadian experimental film-maker Michael Snow’s legendary New York Eye And Ear Control (1964) – with music from a sextet which includes Albert Ayler, Don Cherry and Sunny Murray – is equally absent.

It’s curious that in a book predicated on the importance of improvisation there is but little engagement with hard-core free playing. Ornette Coleman features briefly via Spike Lee’s use of Lonely Woman in Mo’ Better Blues (1990) and his work on David Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch (1991). But there is nothing on the 1965 Chappaqua Suite, commissioned by director Conrad Rooks but unused because Rooks feared the inherent power and beauty of Coleman’s music might detract from, rather than enhance, the visual impact of his film. I would have thought this an instructive episode for Carlson to consider.

It’s equally strange that in a text which focuses in good part on the emergence of positive images and role models of black creativity and culture, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Sun Ra and Don Cherry are absent. Think of the way that in Sound (1967) director Dick Fontaine set the reflections of John Cage in counterpoint with the improvisations of Kirk; of John Coney and Sun Ra’s 1974 collaboration on the Afro-Futurist science-fiction film Space Is The Place, or Don Cherry’s 1973 soundtrack for Chilean-French film-maker Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain – which Jodorowsky called “another kind of music – something that wasn’t entertainment, something that wasn’t a show, something that went to the soul, something profound”.

Coltrane is here. Director Alan Rudolph reveals that he is “more influenced by John Coltrane than John Ford” (p 67) and Carlson’s analysis of the films of Spike Lee underlines the importance of A Love Supreme to the director (ditto Alabama for Terence Blanchard). But there is no mention of the extraordinary mid-1960s encounter between Coltrane and the Montreal-based Canadian filmmaker and Coltrane enthusiast Gilles Grouix (1931-1994) – which led Coltrane to re-record signature pieces of his like Naima and Village Blues for Grouix’s underground art-house hit Le Chat Dans Le Sac. (The music was released by Impulse! in 2019, as Blue World.)

For all her emphasis on improvisation, Carlson believes it essential that contemporary jazz rekindle a relationship with popular culture. And here lies the most contentious part of Improvising The Score. It is one thing to state, as Carlson does, that “jazz’s significations in popular culture […] abound” (p 61). It is another thing entirely to assert (p 157) that “Jazz’s presence in popular culture is essential for its continued growth and longevity.” (I’m assuming that the possessive pronoun here refers to jazz.)

In the America of BLM and Trump – never mind a culturally and linguistically differentiated Europe – what exactly might the term “popular culture” mean – or, if you prefer, “signify”? Many a decade ago, the films of Fred Astaire synthesised and projected “swing-time” jazz and popular culture, attaining the sort of global outreach that might seem inconceivable in today’s world of often fiercely distinctive “tribes”. Such issues are nowhere addressed by Carlson and, unfortunately, all we learn of Astaire (and his dance partners) is that “Fred and Ginger movies” were some of Woody Allen’s favourites. (For a detailed examination, see Todd Decker’s 2011 Music Makes Me: Fred Astaire and Jazz).

At the end of her text, after looking closely at the effects of both Covid-19 and streaming, Carlson suggests that “musicians should consider ways of engaging modern-day audiences through the technologies, modalities and cultural ideologies of the twenty-first century” (p 158). In this “new cultural landscape” video games are apparently “a ripe medium for featuring jazz” (ibid). No wonder Manfred Eicher has spoken of the crucial importance to the creative artist of the faculty of resistance! I’ll leave it to readers to decide just how fruitful or fanciful Carlson’s suggestions may prove to be, and focus, finally, on the most rewarding aspects of Improvising The Score.

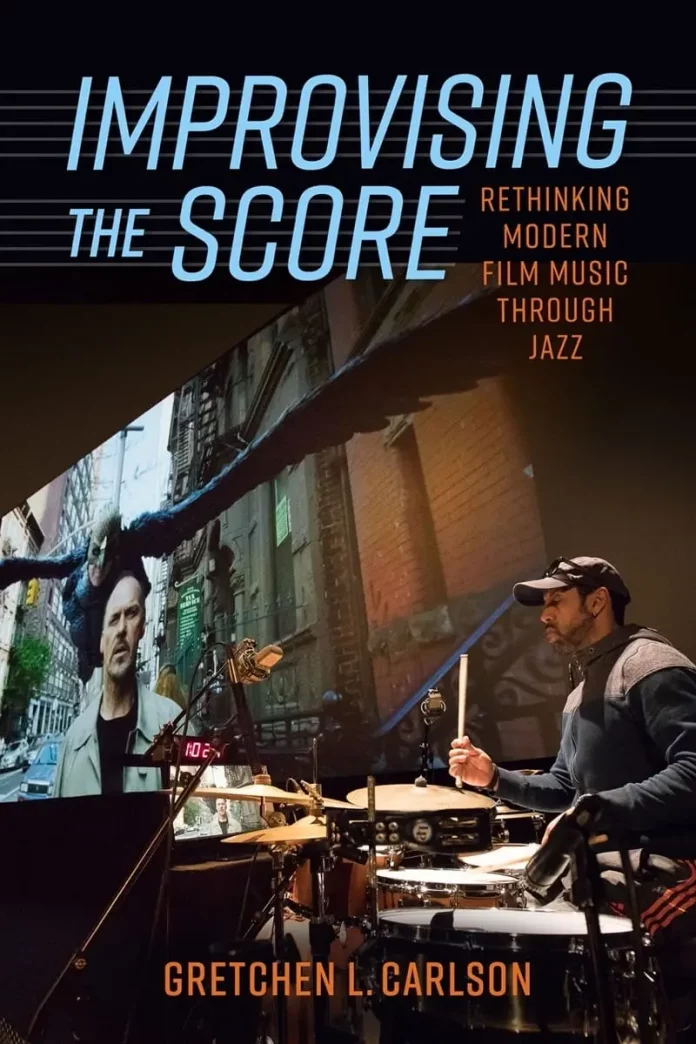

The more accessible of Carlson’s reflections emerge from the old-school format of in-depth interviews. There are both incisive and sustained insights into the collaborative work of Mexican percussionist Antonio Sánchez and his compatriot, director Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu (the 2014 Birdman – where Sánchez played the score before the film had been shot, with the aid of indicative hand-signals from Iñárritu). There’s comment from trumpeter and multi-instrumentalist Mark Isham and director Alan Rudolph (1997’s Afterglow), trumpeter Terence Blanchard and director Spike Lee (the aforementioned Mo’ Better Blues, 1992’s Malcolm X and When The Levees Broke: A Requiem In Four Acts of 2006) and pianist Dick Hyman and director Woody Allen (e.g., 1979’s Manhattan, 1983’s Zelig and 1986’s Hannah And Her Sisters).

Some of the best moments of Improvising The Score come in Carlson’s extensive treatment of Blanchard’s socio-political and historical sensitivity and the combined power and subtlety of his blues-sparked scores. And the stark contrast between the full-on black poetics and politics of Lee and the seemingly white-face nostalgia of Allen’s world (fed by what Carlson calls the “historically informed compositions and performance” of Hyman) makes for some intriguing reading. Carlson considers the case for seeing Allen’s nostalgia as an index, not of escapism, but, rather, authenticity – a key and diversely inflected concept throughout Improvising The Score.

A glance at the 17-page bibliography and 24 pages of wide-ranging footnotes is enough to indicate the admirable amount of research which went into this project. But it also serves to reveal another surprising omission in the text. A reference to “Hedling, Erik: Music, Lust and Modernity: Jazz in the Films of Ingmar Bergman: Soundtrack 4, no 2 (October 2011 pp 88-99)” sounds promising. But Bergman features in Improvising The Score only in the two “puffs” given him by Woody Allen (pp 121 & 130). If Carlson’s research led her to such a specialist reference in Swedish cultural history, one has to wonder why Improvising The Score ignores the key contribution of Swedish jazz to modern improvised jazz filmography: namely, director Stellan Olsson’s exemplary Sven Klangs Kvintett (1976) where the lead character is played by saxophonist Christer Boustedt (1939-1986).

Despite its various omissions and (to my mind) problematic take on the theme of jazz and popular culture today, I would recommend Improvising The Score. It’s a bold and challenging work, overall, which stimulates much thought. And sometimes, the omissions in a book can prove as fruitful as its content. The lack of any mention of the jazz film scores of John Dankworth (who was keen to distance such work from “popular culture”) sent me back to classics like Saturday Night And Sunday Morning (1962), The Servant (1963), Darling (1965) and Accident (1967). I also re-read the musically informative “Sir John Dankworth Talks Film Scores with Frank Griffiths”. So, despite my various reservations, Gretchen L. Carlson – whose further publications I await with interest – gets my gratitude on several counts.

Improvising The Score: Rethinking Modern Film Music Through Jazz by Gretchen L. Carlson. University Press Of Mississippi/Jackson, 220 pp with 12 b&w illustrations, diagrams & musical scores, bibliography, selected filmography & discography, index, pb. ISBN 9781496840844. 2022. £22.71