He played with Roger Miller of King Of The Road fame and with New York rockabilly star Robert Gordon but virtuoso guitarist Danny Gatton, despite almost always being close to ever-popular country music, was rarely in the mainstream spotlight. His lot was exceptional guitar playing, particularly on the Fender Telecaster, and that brought both joy and frustration to the man once described as “the greatest guitar player you never heard”. As Les Paul says during this 90-minute chronicle of Gatton’s music, life and death, “The higher you get, the thinner the air, and the better you get, the farther out you go. When you go out there, boy, the air is thin. So then you’re a musician’s musician and that’s where Danny was going. He played it almost too well.”

The musical borderland in which Gatton existed is summed up in the title of his 1978 album Redneck Jazz (featuring pedal-steel master Buddy Emmons) and in the name of their touring band, Redneck Jazz Explosion. The expression can be taken two ways – on the one hand suggesting the fusion of country tone and phrase with bebop and blues that characterised Gatton’s music and on the other chiming with the idea that Gatton was a “blue-collar virtuoso”. In other words, although he was working class (redneck), he was sophisticated (jazz). Leaving out heavy rock, he was certainly an all-round electric guitarist. He says “I was always obsessed with learning everything – rhythm and blues, and country, and rockabilly, and rock ’n’ roll, and jazz.” Live, in a slot he called “imitation time”, he would play in the styles of, for example, Link Wray, Scotty Moore and Les Paul.

His father was a guitarist and metal worker, and the two strands – art and practical craft – run right through own Gatton’s life and being. If he wasn’t playing guitar he’d be restoring old cars or building hot rods, often for a living. One thinks here (and on hearing Gatton’s delicate manipulation of bends and slides on Harlem Nocturne) of English guitarist Jeff Beck, a dual guitar and hot-rod enthusiast who, unlike Gatton, had more celebrity connections. Gatton got his metal-working skills after his dad insisted he get a trade, knowing how unstable the music business was. Gatton says “I played six nights a week and jam sessions on the weekends and still had to get up and do sheet metal work every day, and cut my hands up.”

Thus Gatton’s life became, as his mum Norma Gatton puts it, one of “cars and geetars”, the guitar winning over full-time metal work. In 1964 he met his future wife Jan at the National Science Foundation where they both worked and where he was doing his sheet-metal apprenticeship. By then he’d had enough of hitting his thumb with hammers and told her a week after the wedding that he’d be a full-time guitar player. Both Norma and Jan and, to a lesser extent Danny and Jan’s daughter Holly, push the story along with frequent commentary and narrative as well as insights into Danny’s character. Other narrative detail comes from interview clips with Les Paul, Robert Gordon, Joe Bonamassa, Joe Barden and Gatton’s lesser-known musical associates.

The practical strain in Gatton’s makeup led him to have a mechanistic view of the guitar (that some might say fed into his concern with virtuosity – the film’s title, The Humbler, comes from Gatton’s ability to outplay the competition – though he was noted for his modesty). He knew about gear and modified it, just as he did with cars; for a while he ran a guitar repair shop. The famous Fender Telecaster that he’s often seen with was a 1953 model that came from Zavarella’s Music in Arlington, Virginia in 1974 and was paid for on monthly instalments, supervised by Jan. Until then he was playing Gibson guitars. Joe Barden says Gatton’s move to the Telecaster was inspired by Roy Buchanan. Tom Principato tells us Gatton adopted the most basic setup – “an old Telecaster, an old, beat-up four-ten Bassman and an Echoplex and he got every sound in the world out of it”. In the early 1980s the Tele got a custom stainless-steel bridge and blade-style humbucking pickups pioneered by Joe Barden that, it’s said, tracked Gatton’s virtuoso playing better than single coils. There was also, in the late 70s, the Magic Dingus Box that offered a looper, vibrato and more, but he reverted to a simple guitar into amp setup after being dubbed “Danny Gadget”. By the way (it’s not often remarked but a photo online of an autograph session shows), Gatton was another of a long list of left-handers (Joe Pass, Mark Knopfler, etc) who became outstanding players of right-handed guitar.

There was no doubt about the virtuosity, embodied in such records as American Music (1975, Aladdin) and Redneck Jazz (1978, NRG). Gatton was pleased by the latter record, saying “Finally, after all these years I did something I like.” But it was financed by his mum and illustrated how difficult it was for someone who was strictly an instrumental virtuoso (no singing) to break into a bigger market via a major record deal. This might partly reflect the end of the heyday of instrumental jazz (Brubeck et al did fine without singing) as vocal-led pop and rock came to dominate the non-classical scene through the 60s and 70s. Gatton might be seen as being born out of time, but even in the 1950s, vocals probably still dominated the popular market.

Gatton sometimes blames the difficulty of finding a big deal on his eclecticism, observing that the record business always sought to slot music into marketable categories. American Music ranged across many styles and Billy Hancock, who sang and played bass on the album, says the critics “had a field day panning it,” reckoning it sounded “like somebody’s sampler” because of its variety. Ironically, eclecticism in the arts has long moved beyond national borders to become a politically marketable commodity in these inclusive times, and albums with titles like American Music and Redneck Jazz might be construed in Trumpian terms as conveying patriotic exclusivity. Nevertheless, Gatton, within his musical ambit, hoped to open people’s minds. There are many extracts in the film from an interview with British journalist Howard Thompson and in one Gatton says: “We just weren’t content playing what people wanted to hear. . . We figured we could educate them into something more. Wrong!”

As far as guitar style is concerned, Gatton is rather recognisable, even though others such as Glen Campbell, Herb Ellis, Chet Atkins and Les Paul and, earlier, players in the Western Swing style had mixed jazz and country. That identity is largely down to sheer technique on the Tele, although in recent years exceptional Tele technique (see YouTube) has become rather commonplace. There is a heat, attack and rawness of sound in Gatton that reminds of Django Reinhardt, who brought a similarly vital edge to swing guitar playing. However, for a full picture of guitar technique in the 70s and 80s one would have to take into account players such as Allan Holdsworth, Eddie Van Halen and their progeny.

Eventually, Gatton got a major deal – for seven albums with the Elektra label. The first, 88 Elmira St (1991), prompted reviewer Bill Milkowski to say “At long last, a Danny Gatton album with Jeff Beck production values.” The second, Cruisin’ Deuces (1993), showed Gatton breaking out of the country bebop mode with some more funky material, but still in the all-American mould, the record accompanied by the slogan “No one plays the routes of American music like Danny Gatton.” But that was it – there were no albums three to seven. Gatton was “released” from his Elektra contract in August 1993, presumably for not selling enough. Gatton says of the experience “I can’t come on as Mister Showbiz, ’cause I’m not – I’m the local guy next door, you know, that just happens to play better than most people.” Over a Christmas 1993 family video he says “I’ve had it with the business.”

In early 1994 he did the album Relentless with Joey DeFrancesco on Big Mo records, featuring a quartet playing blues, jazz and shuffle. (In 1992 he’d been further into contemporary jazz on New York Stories, a Blue Note album with Bobby Watson, Joshua Redman, Roy Hargrove and others.) But Jan remembers that that summer he told her that “his heart was broken . . . and there’s nothing left in there . . . I’m empty”. His mother refers to strokes, saying “His hand would go numb,” and he reported that the left side of his body had gone numb for 11 hours and that at one gig he had had no feeling in his left arm and had to fake the playing. Daughter Holly says “He was drinking a lot more, and pulling away. He wouldn’t always have dinner with us, he’d stay out in the garage.” On 4 October 1994 Gatton shot himself in the palatial building at the family home in Newburg, Maryland that he called “the garage of my life’s dreams”. He had tried similarly to end things a decade earlier when Jan had intervened and wrestled the gun from his head.

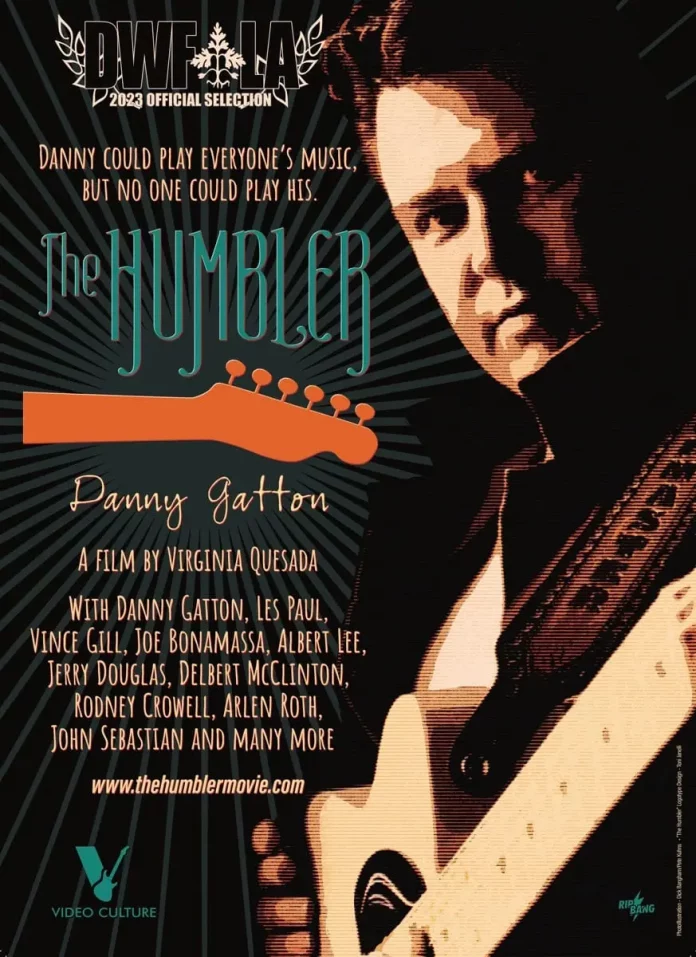

This film – a multi-year labour of love by Virginia Quesada of the non-profit arts organisation Video Culture, Inc. – is very professionally made and tells Gatton’s story with plentiful film and audio clips of the man in action, including previously unseen footage and photos. As a story of a man’s life and of a period of American social and musical culture it’s well worth an hour and half of anybody’s time – not just for those who play guitar. Gatton was locked in his era – most musicians are – and the musical world has moved on but his life and music have long deserved a thoroughgoing chronicle such as this.

The Humbler, a film from Video Culture, Inc., directed by Virginia Quesada; 93:33 minutes. video-culture.org; thehumblermovie.com