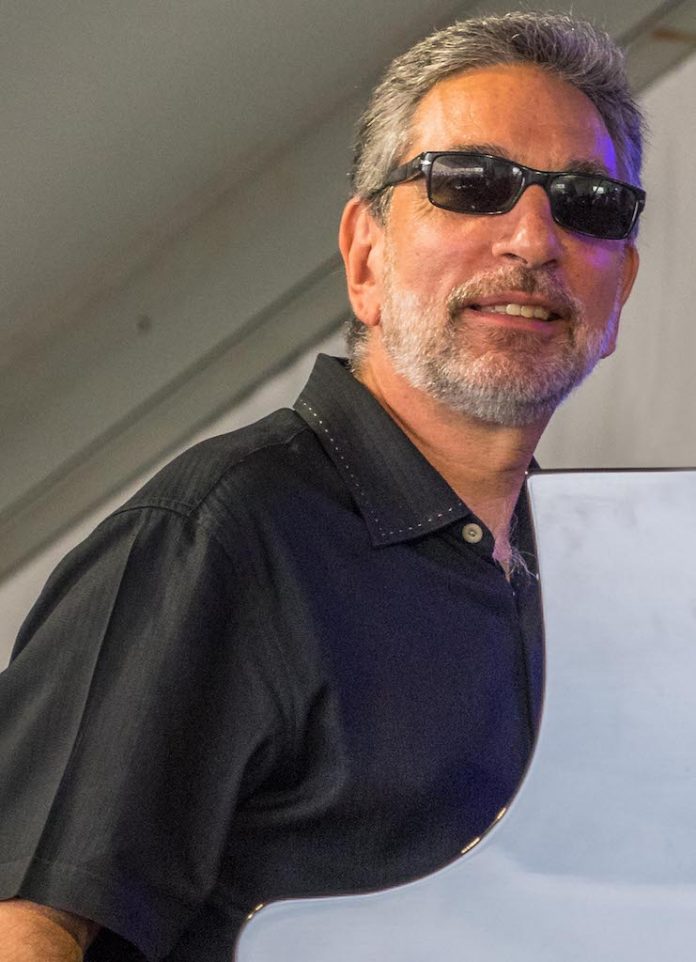

One of the live routines of Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet is a dedication to organist Jimmy Smith, titled The Boss. The Groover Quartet is LeDonne’s organ combo, which has been enjoying a successful residency of 15 years at the club Smoke in New York City. The 62-year old pianist and organist has turned into quite a boss himself. He’s an acclaimed pianist whose career path includes stints with Milt Jackson, Benny Golson, Sonny Rollins and Dizzy Gillespie, as well as a poll-winning Hammond organist. Switching from piano to organ is like alternating a tournament of table tennis with a marathon tennis match on gravel court. What’s his secret?

The baritone voice of LeDonne is grandfatherly, the imaginary soundtrack to the crackle of fire blocks and scent of marshmallows. He says “Each instrument certainly requires a different approach. You don’t control the sound with your fingers on the organ, while the piano requires subtle muscle control and needs power. My touch is pretty percussive on the piano and I love to belt out the bass lines on the organ pedals. Hard-driving rhythm means everything to me, that’s my thing! But at the same time the walking figures on the organ keyboard have to be relaxed to stay in tempo. I probably play incorrectly, because I’m self-taught on the rather complicated organ. You need about four brains to play it. But I’ve been playing it since my childhood”.

Soul jazz: ‘I don’t like that term. It’s patronising to all-round, hard-working musicians. All jazz is soul jazz’

LeDonne was born as the son of a jazz musician and music-store owner in Bridgeport, Connecticut, a former industrial town that was skipped by the waves of urban renewal. Plenty of funky hoods. “I loved it! I spent all my time in the store of my father. I listened to his classic jazz records. I liked Sly Stone and James Brown and played Farfisa organ by age 10. I had a little band going. One summer day, when we were rehearsing in the basement, neighbourhood kids were suddenly dancing in front of the window. That felt so good. I knew then that more than anything else I wanted to be a musician that makes people dance. Essentially, I still feel that way. I like my audience to feel like dancing”.

So one could safely argue that soul jazz ran through his veins from day one? A sudden reaction in LeDonne’s clear brown eyes, which are underlined by a prickly grey beard, is evident: “I don’t like that term. It’s patronising to all-round, hard-working musicians. All jazz is soul jazz. But I do understand what it tries to convey. I never thought I’d simultaneously be a modern and a soul jazz guy. My music comes from my experience. So instead of How High The Moon I’ll play Love Don’t Love Nobody by The Spinners, because I grew up with such great tunes. Our crowd at Smoke is a mix of old and young. The youngsters know Michael Jackson’s Rock With You. I instil it with swing. Then those youngsters say to me ‘Hey, I didn’t know jazz sounded like this!’ Basically, it’s music that’s underscored by the black American aesthetic. It’s hard to explain. It has a certain kind of soulfulness, the feeling Miles Davis described when he listened to Billy Eckstine’s band with Charlie Parker: ‘It gets all up inside your body’”.

‘…the reason I play organ at all is Brother Jack McDuff. I had stopped playing organ in college. I had become your typical idiot college kid immersed in “complex” piano stuff’

Davis might as well have referred to the sound of the Hammond B3 organ. The instrument is made for the blues and able to whisper or scream in the detailed manner that more than a few star-crossed lovers view with envy. LeDonne runs the whole gamut of the B3, from the orchestral sweep of Wild Bill Davis to the lurid bebop lines of Don Patterson. He blends churchy balladry and Coltrane-ish sheets of sound into a dynamic mix. “I love the whole evolution of styles. It takes years of practice and experience to coax all of that from that machine, I can tell you that! My influences are Jimmy Smith, Don Patterson and Melvin Rhyne, who was Milt Jackson’s favourite organist. I love Charles Earland, whose swing and monster bass line is of another level. And one of the guys that inspired me most is Lonnie Smith. He covers all bases. So I figured I didn’t have to stick to one style”.

“However, the reason I play organ at all is Brother Jack McDuff. I had stopped playing organ in college. I had become your typical idiot college kid immersed in ‘complex’ piano stuff. Then I moved to New York. My friend Jim Snidero played with McDuff and took me to a gig. McDuff was playing with the legendary organ jazz drummer, Joe Dukes. Jim told McDuff that I played organ. Jack asked me to sit in. Oh my God! I hadn’t played organ in five years. I played a blues and he loved it. He said that I should really pursue playing organ. So I went and bought a new organ. That was the beginning of my organ jazz career. It’s McDuff’s fault!”.

This is the same fellow who played with such diverse key figures as Benny Goodman, Roy Eldridge, Clifford Jordan and Barry Harris, learning by rote, walking away with the residuals of those experiences. He was mentored by Jaki Byard. “Byard was a bonafide genius. He could play any style and remain real. He had his own crazy way of playing bebop lines. Herbie Hancock picked up on it. Byard was a bridge to Herbie’s free thinking. He was such a sweet guy. He’d play some incredible stuff, just laugh and say ‘You like that?’”.

‘There’s too much stress on innovation for young musicians in the United States. It’s ridiculous and an incentive for egomania. I’ve been with so many of the masters. None of them thought “I have to innovate”‘

The struggle of straightforward jazz in the current hype-crazed climate is on every jazz buff’s tongue. How is LeDonne, who takes pains to mentor the new generation of players, holding up? “There’s too much stress on innovation for young musicians in the United States. It’s ridiculous and an incentive for egomania. I’ve been with so many of the masters. None of them thought ‘I have to innovate’. It’s either a part of you or not. If not, that’s ok too. There were so many great players that didn’t innovate at all, except maybe stylistically. Only a few, like Armstrong and Parker, changed the whole ballgame. I think I can safely say that I’m the opposite of self-centered. Because of playing with the giants, but most of all because of my daughter”.

Mary, the daughter of LeDonne, is disabled – non-verbal and legally blind. For five years now, LeDonne has been heading the Disability Pride Parade, a fundraiser for what he calls ‘another ethnic minority’ in the USA. “This is the greatest thing I’m doing, a calling. All because of Mary, who is me and my wife’s greatest gift. The disabled are extraordinary people. Communication is different and quite a task, but once you reach a point of understanding, it actually is thrilling, a blessing instead of a hardship”.

“Running this organisation is strikingly similar to a career in jazz. There’s no blueprint, you persevere and refuse to fail. That’s in the DNA of a good jazz musician. Just like empathy and mutual understanding. These are the things that Mary has taught me to be more conscious of. I have to make a living, of course, but I don’t let the pressure get on it. I’m relaxed and I focus on sharing my music with the audience. If I can make it feel something with what I consider to be my calling, I think I’m successful. The rest is pure nonsense”.