It’s a long time ago but I still remember buying Gerry Mulligan’s 1961 Presents A Concert In Jazz – and playing it almost ceaselessly over the next few weeks. Gary McFarland’s Chuggin’ was one of many gems and it featured trombonist Willie Dennis who was a new name to me at the time.

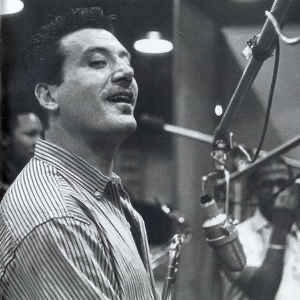

Unlike his contemporaries, who had mostly fallen under the spell of the great J.J. Johnson, Dennis’s roots were clearly in the more expressive Bill Harris school. Almost free of articulation and barely seeming to tongue at all, he used slurs and glissandos to create overtones as he moved between slide positions – often alternate slide positions.

Many years later I asked Eddie Bert, who knew him well, to explain how he did this: “Willie had a unique style and sound playing some notes out of the usual positions and doing something we call ‘crossing the grain’. The trombone has seven positions and each one has a series of overtones starting with an octave, then a fifth, then a fourth and a third and as you get higher the intervals are smaller. If you move quickly from the first position to the fourth, for example, you can play these overtones up high and ‘cross the grain’, which Willie did a lot.”

Willie Dennis (William DeBerardinis) was born 10 January 1926 in Philadelphia and was mostly self- taught on the trombone. He began working with the popular Philadelphia-based big band led by Elliot Lawrence on the local WCAU radio station. He made his recording debut with Lawrence in 1946 on a 78 rpm single featuring vocalists Jack Hunter and Rosalind Patton. An interesting but short-lived addition to the band at that time was Mitch Miller on oboe. Dennis was on two broadcasts with Elliot later that year which have subsequently been released commercially – the Meadowbrook Ballroom in New Jersey and the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York City. In the late 40s he also worked with Claude Thornhill and Sam Donahue but did not record with them.

Around 1951 Dennis began studying with Lennie Tristano at his studio on 317 East 32nd Street in NYC, joining a group of students that included Lee Konitz, Warne Marsh, Don Ferrara, Ted Brown, Billy Bauer, Peter Ind, Sal Mosca and Ronnie Ball. In his book Jazz Visions Peter Ind says “Some of the most exciting musical times I remember were with Lee, Warne, Don and Willie playing those incredible lines composed by Lennie, Lee and Warne. Lennie recorded some of this music but I have no idea whether the tapes still exist.”

Willie, along with Marsh, Ferrara, Mosca and Ind would occasionally travel to Konitz’s house in Elmhurst, Long Island to rehearse. Konitz once told me that he considered Willie to be a “wonderful trombonist and a lovely guy but I didn’t know him that well because he used to drink and hang out at places like Jim & Andy’s. Being a family man I didn’t hang out there.”

Regular work was scarce and sometimes the musicians had to take day jobs. Ind and Konitz both worked occasionally in the mail-room at the British Information Office and Dennis took temporary employment as an attendant at the Museum of Modern Art. Coming from a relatively affluent background Marsh probably did not have quite the same financial pressures as the others but he did give occasional saxophone lessons. (His father was the celebrated cinematographer Oliver T. Marsh, whose credits included David Copperfield, A Tale Of Two Cities and The Great Ziegfield. Sal Mosca, Peter Ind and Don Ferrara taught throughout their careers and around 1955 Mosca gave piano lessons to a very young Bob Gaudio who wrote numerous hits for the Four Seasons.)

We have Bob Sunenblick to thank for a fascinating insight into the trombonist’s work with Tristano. In 2014 Uptown Records released a previously unissued double CD of Tristano’s sextet performing at the Blue Note in Lennie’s home town of Chicago in 1951 (Uptown UPCD 27). The other members of the group on this historically important release were Lee Konitz, Warne Marsh, Buddy Jones and Mickey Simonetta. The billing on the illuminated marquee was “Lennie Tristano With His Great Band and Slim Gaillard’s Trio” – an intriguing if somewhat incongruous combination which might explain the bizarre request for Tennessee Waltz, a big hit at the time, from a member of the audience. Presumably Peter Ind, Arnold Fishkin and Al Levitt or Jeff Morton – Tristano’s regular accompanists – were unavailable. Buddy Jones was playing bass with Buddy DeFranco at the time and went on to perform with Elliot Lawrence, Al Cohn, Joe Newman and Manny Albam among many others. The obscure Simonetta was a local drummer and his only other recordings were with Danny Bloc in 1953 and 1954.

Willie’s powerful, choppy phrasing combines well with the more cerebral, vibrato-free work of Konitz and Marsh

Standards were always a rich vein of inspiration for the Tristano school and the 14 Uptown titles are either well-known tunes or songbook contrafacts, among the latter Sound Lee (Too Marvellous For Words), Two Not One (I Can’t Believe You’re In Love With Me), Sax Of A Kind (Fine And Dandy), Background Music (All Of Me), No Figs (Indiana), Palo Alto (Strike Up The Band), Judy (Don’t Blame Me) and Tautology (Idaho). Just as an aside when Tristano announces Judy, “written for a very nice lady”, he does not inform the audience that he wrote it for his wife Judy Moore Tristano. There are two versions of All The Things You Are and it is worth pointing out what Jerome Kern’s sophisticated harmonies continued to mean to Lee Konitz. In a Downbeat interview he once said “I could just spend the rest of my time playing All The Things You Are,” and as if to stress that point again he told writer Andy Hamilton “I mean that.”

On this session Willie’s powerful, choppy phrasing combines well with the more cerebral, vibrato-free work of Konitz and Marsh and he has his own ballad feature on These Foolish Things where he is centre stage. Reviewing the engagement in Downbeat, Jack Tracy called Dennis “A fabulously facile musician who comes close to Warne’s and Lee’s standards.”

In September 1953 Dennis made his first album with Charles Mingus on a live date with three other trombones in the line-up – J.J. Johnson, Kai Winding and Benny Green (Jazz Workshop Prestige UPCD 24097). It was essentially a jam session recorded on Mingus’s own Debut label at the Puttnam Central Club in Brooklyn. All four trombones stretch out at length and Willie certainly holds his own in this heavy company on numbers including Move, Wee Dot, Ow and Now’s The Time. When the album was reissued in 1964 Ira Gitler gave it three and a half stars in Downbeat. A month later Dennis performed with Mingus’s octet and is heard briefly on Miss Bliss (Original Jazz Classics OJC CD1807-2).

In March 1956 he performed on Englishman Ronnie Ball’s first and only date as a leader in the USA (Fresh Sound FSRCD 570). The pianist had arrived in New York in 1952 and immediately began studying with Tristano. For this recording he added fellow student Ted Brown to the front line on tenor. Wendell Marshall and Kenny Clarke, who had worked with Tristano the year before, were recruited to add their subtle uplift to the rhythm section. The leader included two of his originals – Pennie Packer (a minor variant of Pennies From Heaven) and Citrus Season (based on Limehouse Blues). This was Ted Brown’s first recording date and he contributed Feather Bed (from You’d Be So Nice To Come Home To) and Little Quail (I’ll Remember April) to the repertoire. He also transcribed Lester Young’s famous 1940 Tickle Toe solo calling it Prez Says. (Learning classic jazz solos was a regular Tristano teaching device and another good example of this practice is a 1957 Lee Konitz date with Don Ferrara (Gambit Records 69253). On Billie’s Bounce they play Charlie Parker’s four choruses from the 1945 date with Miles Davis and the unison is so perfect one could be forgiven for thinking they must be reading it. Ferrara confirmed to me they were actually playing from memory.)