By the time he wrote this book Mr Yanow had written more than 20,000 album reviews and 917 liner notes. This is his 12th book. It’s doubtful if anyone would be able to claim to have produced more. Remarkably, I have always found his reviews to be both sensitive and accurate, to the extent that one can safely acquire an album after reading what Mr Yanow has said about it. The last reviewer to be so prolific was Leonard Feather, seen off, incidentally, by Yanow in these pages.

As the book is self-published it hasn’t had the benefit of a good editor, who would have been able to decide what to leave out. You might not be riveted by the news that “a search through Tom Lord’s superb jazz discography reveals that not a single jazz recording took place” on 4 October 1954, the day of Mr Yanow’s birth. Nor does the book have an index – an unusual inconvenience these days.

As its subtitle suggests, these are extremely personal memories divided by roughly 25 chapter headings and with six appendices. At the heart of the book are three comprehensive interviews, done some time ago, with trumpeters Freddie Hubbard (16 pages) and Maynard Ferguson and with pianist Chick Corea (17 pages). Maynard takes up 19 pages and Yanow’s questions guide him through interesting events. I have always regretted missing the opportunity to talk to this interesting and phenomenally talented man. One of the major questions that I (and incidentally Humphrey Lyttelton) wanted to ask Maynard was, regarding the ultra-high notes, how. We had decided that Maynard had a larger than normal upper-mouth cavity. Apparently not so. Yanow obliged with the question.

“I’m self taught on that part. Years later when I met people into yoga, I discovered that I breathe almost perfectly, which very few people do. I was playing in the upper register when I was very young . . . It’s a thing of coordination and the air power is important. You can’t just play a high note and then collapse, you have to have stamina. I like to swim 100 laps in the pool each morning when I’m home . . . it’s really so I have my air power. As opposed to a baseball player or a basketball player, we can have longevity in our musical career if we keep ourselves in good shape.”

Hubbard obliged with his experience of Art Blakey and the drummers. “You had to swing to play with Art. He’d swing awful hard, no jive . . . I left because Art wasn’t letting me expand and grow. I always liked Elvin Jones and Tony Williams, that kind of drummer. Art is very set in his own style and I didn’t want us to get in each other’s way. I figured I could write more too because with that band, Wayne Shorter was the writer.”

Yanow shows insight in a chapter on jazz critics. Of Feather he writes: “He did not care for Dixieland, avant-garde jazz or fusion yet he often reviewed performances in those genres. If he did not like an artist on a personal basis, they often received a negative review no matter how worthy their music. And because he was such an influential figure, his written words could do damage even when that was not his purpose. So while many readers took his words as gospel, he was disliked by many others (including some musicians) for a variety of reasons.”

Elsewhere Yanow has created a vivid portrait of Roland Kirk, counterbalanced by details of how much he paid for concert tickets. But in the face of such detail one has to remember that he does emphasise how personal his book is.

The appendices contain lists, one of which is a good bibliography, that mainly take up too much space. The first one has “112 major jazz artists of the past” – well-intentioned, but unfortunately including pianist Abdullah Ibrahim who, as far as I can ascertain, is not yet dead – at least they’ve sold tickets online for a tour this summer.

One of Mr Yanow’s happy hunting grounds was the substantial (1472 pages) All Music Guide To Jazz. He realised when he first discovered the book that a lot of the biographies and album reviews (its raison d’ être) were not very good, so he wrote to the publishers and suggested that he should be allowed to contribute most of them himself. They agreed, and Mr Yanow is proud that, since his name appears at the end of each review, it is perhaps the most published name in jazz history. I don’t suppose I’ll ever catch up.

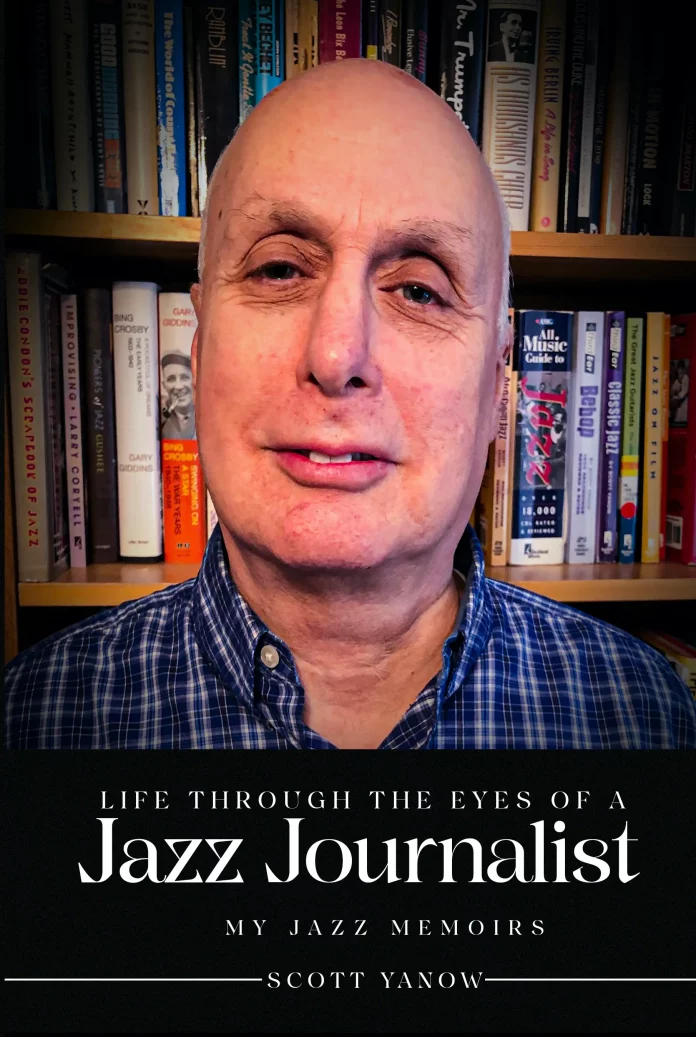

Life Through The Eyes Of A Jazz Journalist – My Jazz Memoirs, by Scott Yanow. Self-published on Amazon, 291pp, pb, £20.