When Hazel Miller phoned me on Sunday to say that Keith Tippett had died, I felt it was like the end of an era; too many of that generation falling away. He had been in and out of hospital for two years following a heart attack and was readmitted last week.

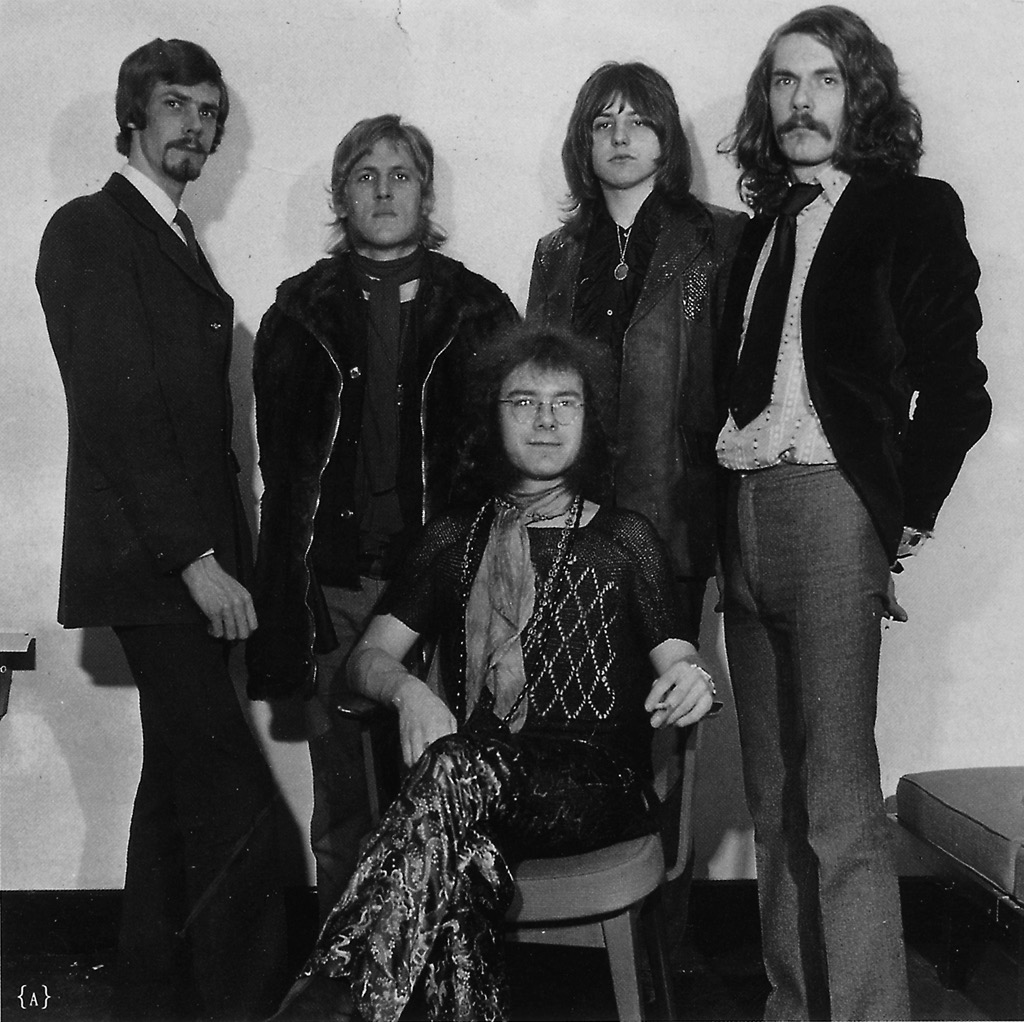

Born in Bristol, pianist Keith Tippett moved to London in 1967, quickly establishing himself on the music scene, playing with progressive rock bands such as King Crimson (and even appearing on Top of the Pops), and being heard regularly on the jazz circuit with the emerging generation of young free players he was to be closely associated with – saxophonist Elton Dean, cornettist Mark Charig and trombonist Nick Evans. As the Keith Tippett Sextet (Tippett had dropped a final “s” to make it easier to say) they recorded You Are Here… I Am There (1970) and Dedicated To You, But You Weren’t Listening (1971) but it was Tippett’s huge band Centipede that caused a stir.

A conglomeration of 50 musicians (hence the name) combining 19 violins and cellos with a collection of rock, jazz and free improvisers, Centipede had its debut at the Lyceum in 1970, followed by an album release, Septober Energy, on RCA/Neon the following year. It included Ian Carr, Alan Skidmore, Dudu Pukwana, Mongezi Feza, Paul Rutherford, Robert Wyatt, Karl Jenkins, Zoot Money, Maggie Nichols and Julie Tippetts (formerly Driscoll). Valiant and adventurous, it encompassed rock riffs and solos with free improvisation, but met with mixed reviews. However, it was an indication of the possibilities which could be explored.

As guitarist Brian Godding was later quoted, (for Lin Bensley’s article, Jazz Journal June 2019): “Musicians from totally diverse backgrounds all contributing to a musical extravaganza conceived and constructed by Keith, amazing! My personal memories are of a big adventure unravelling as this ‘tribe’ of people came to grips with the concept of structure and improvisation intertwining seamlessly. In its short lifespan Centipede performed some of the most creative ‘happenings’ I’ve experienced as a musician.”

Tippett and Julie Driscoll had met when he (with Dean, Charig and Evans) had worked on her Georgio Gomelsky produced album 1969 (recorded in that year, released 1971). As he was later to recall: “We were introduced and were then literally locked in all night at Polydor’s studios until the cleaners came in the morning. Julie would play her songs and say ‘I would like some brass here.’ We worked all the way through the night and we fell in love.” Their close relationship – personally and professionally – led to a long and enduring marriage.

Another RCA album, Blue Print, followed in 1972, but Tippett moved away from the vagaries of the big companies towards smaller independent labels, notably Harry and Hazel Miller’s Ogun Records. Harry Miller had been one of the bassists with Centipede and this opened up a new area of association. Tippett was to record consistently for Ogun over the years.

A much respected and innovative performer and composer, he extended the boundaries of the music he was involved in, fusing composition with improvisation, whether in large or small-scale units, solos or duets. He worked with other pianists, famously duetting with Stan Tracey, recorded as Live At Wigmore Hall in 1974, relived in 2008 when the pair performed at the Barbican, and several times with Howard Riley, a memorable performance at Goldsmiths College in 1981. As a solo performer, he moved in and out of conventionality, at once sensitive and lyrical, then forthright and dynamic; the “Mujician” was a term given him by his daughter Inca and used for his solo albums on FMP.

He had an interest in film music, reflected in Ogun’s Frames (Music For An Imaginary Film), another of his large groups, and his work in this area included a collaboration with violinist/composer Alex Balanescu for Cowboys, a series of five cartoon films, and as part of the 1995 Meltdown Festival at the South Bank he appeared at London’s National Film Theatre, improvising as a soloist to four short silent films by Polish director Władysław Starewicz.

He will be remembered by many for his connection with the South African contingent based in London, fortunately documented on Ogun in work he did with Louis Moholo-Moholo, Harry Miller, Mongezi Feza, Dudu Pukwana and others, culminating in the Dedication Orchestra. Others will recall nights at the Phoenix, Seven Dials, The Plough, Bedford College, Upstairs at Ronnie’s and countless other venues, both here and on the continent, where he was held in high esteem. Then there was the freer side when he played and recorded with European improvisers – Evan Parker, Peter Brötzmann, Hans Reichel, Trevor Watts, John Stevens and Paul Dunmall, to name a few – and, of course, with Julie.

As a person he was much liked and appreciated; he was of the generation of players who regarded music as an integral part of individual and collective life, committed to discovery, progression, toleration and understanding. As he said, “May music never become just another way of making money.” His gentle West Country lilt and unassuming manner will be missed.

Keith Tippett (Keith Graham Tippetts) born Southmead, Bristol, 25 August 1947; died 14 June 2020.