There was no-one anywhere in my chosen jazz community who failed to express sadness when Steve Voce died, 23 November 2023. “What a wonderful man” said my friend the great jazz double-bassist Dave Green, when I rang him in February this year. “I loved him. He knew the music. And he was such a generous man; an enthusiast who loved to share it too. Once he managed to record me with Roland Kirk when we played down at Southampton (how he did that I don’t know) and sent me the tapes afterwards. And we also did his show Jazz Panorama live in Liverpool at one point with Humph’s band and afterwards he sent me all the tapes again. We used to talk on the phone too and quite recently I told him I was playing in Southport. He said he’d come over – about a 14-mile drive – but later he rang to say he couldn’t make it and would I drop in and see him on my way home? So of course I did, and he gave me about 30 of those magnificent Mosaic box sets to take home. Whether he thought something was coming to an end – well, I don’t know!” The gift does sound a little like the beginnings of a relinquishment of a lifetime passion.

Steve Voce was the last of the generation that wrote about what many people would call jazz’s golden years while those years were still going strong

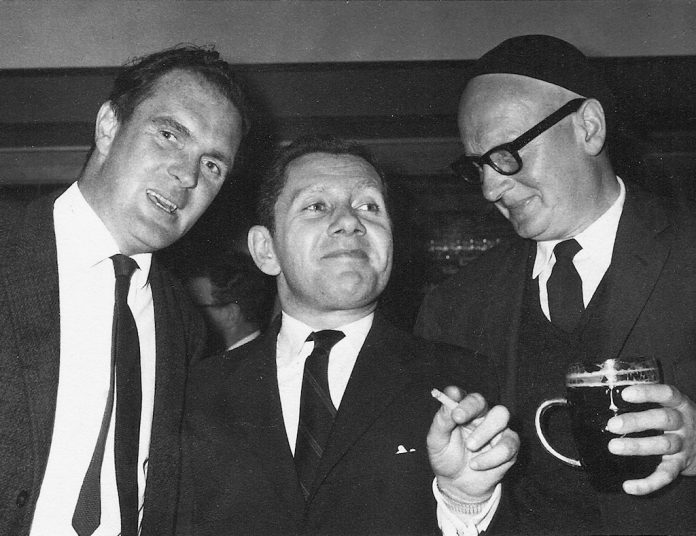

Steve Voce, born in 1933, was the last of the generation that wrote about what many people would call jazz’s golden years while those years were still going strong; in the same generation were Humphrey Lyttelton, Peter Clayton, Alun Morgan and Charles Fox. Like Lyttelton (only 11 years his senior, and one of his closest personal friends for decades), Steve shared both an enjoyment of silliness for its own sake and also the ability to knock stupidity – or even personal dislikes or disagreements – into the outfield with a blunt instrument. This could come in handy in the days when rock music had yet to cement itself immovably into popular culture, and in the world of jazz there was still room for lively in-fighting in the journalistic world. One regular opponent for Steve was the irascible author-journalist-agent Jim Godbolt (whose written joustings with the great clarinettist Sandy Brown are similarly documented in The McJazz Manuscripts, edited by partner David Binns in 1979). The Voce-Godbolt rivalry pertained until, in 1986 Steve jocundly sent Jim a copy of his well-researched biography of Woody Herman in the Jazz Masters series. His rival shredded the book and sent it back to him in a jiffy-bag.

For me Steve’s column in Jazz Journal (called in 1970) “It Don’t Mean a Thing” was usually a first-read and it was that year, in April, that I submitted to the magazine (under my birth-name of “Richard” not my nickname “Digby”) an article called “The Problems of Pop”; a potentially risky submission to the artistic territory of what a later editor Eddie Cook (for better or worse) would call “The World’s Greatest Jazz Magazine”. In the piece I discussed the implications of the 20th century’s greatest cultural revolution post-Beatles and its social impact on our music, coming to the conclusion (accurately or otherwise!) that jazz and pop could survive quite happily and independently of each other in the future. I was aware that any discussion of pop music in his pages might infuriate Steve and opened the May edition with trepidation. But he let me off lightly. “Knowing of its impending publication”, he wrote, “I had been highly suspicious of Richard Fairweather’s article titled ‘The Problem of Pop’. In the event it was a well-reasoned and sensible essay.” It seemed I had escaped his wrath and from then on Steve Voce and I were friends on paper and in principle, though not yet in person.

The first of our meetings, as I recall, was when I had the post of “artist-in-residence” which I shared with the late pianist Stan Barker at Southport’s Arts Centre on Lord Street from 1979 until the mid 1980s. Once a month every Tuesday we played in the centre’s smaller bar (appropriately called “T’Other bar”); Steve was a visitor, liked what he heard, and subsequently (with his faithful and loving amanuensis, wife Jenny, to whom I am in debt for details of this piece) came back with a big Ferrograph tape recorder to record what he heard for Jazz Panorama (which he did for BBC Radio Merseyside). Having done so, and broadcast the results, he then presented the master-tapes to me; thus making available the work which I have always regarded as my best on record; a supreme gift to any musician. The results are still available on George Buck’s Jazzology label in a double album called Something To Remember Us By. Though (somewhat) hidden away in New Orleans under the benevolent guard of Lars Edegran they are still worth a listen.

Jazz Panorama, which ran for well over 30 years until it was mercilessly (and in my view unforgivably) chopped by the traitorous BBC, was one of the best jazz programmes anywhere

Jazz Panorama, which ran for well over 30 years until it was mercilessly (and in my view unforgivably) chopped by the traitorous BBC, was one of the best jazz programmes anywhere and should have been transmitted nationally. Steve was a superb natural broadcaster – he never used scripts unlike Humphrey Lyttelton, Peter Clayton or me – and I was constantly (and occasionally uncomfortably) aware that producers like Keith Stewart and later Terry Carter, who produced programmes of mine including Jazz Parade and Jazz Notes saw Steve potentially as a superior man for the job. Indeed he was regularly called in to broadcast nationally (subbing on occasion for Humph or Peter Clayton). Normally confined to Merseyside, he was capable of creating not just first-class programmes but weaving skeins of radio magic by linking up American interviewees with British counterparts on the line, so that Humphrey Lyttelton (for example) could find himself in a three-way chat with Ruby Braff and Buck Clayton, live on air. Such international conversations were many and varied over the years and jazz history would be much the richer for their recovery. Steve (like me again), also revered the immortal cornettist Ruby Braff who became a regular guest on his shows, and on my desk I have CDs of many of them. (The ever-generous Steve would send me dozens of carefully packed such treasures after any telephone call, however brief). Interviewing sans script and preparation is not an easy task for many broadcasters but Steve, because of his encyclopaedic knowledge of the music, made light work of the challenge. He was also superb at good-humouredly and seamlessly rescuing a programme (particularly with Ruby) when it had got off on the wrong foot or veered off course later. I always remember (with a mixture of sympathy and delight) one such occasion when Steve had confirmed Ruby’s birthplace as Boston and mentioned light-heartedly as his broadcast began: “Max Kaminsky’s from Boston too, isn’t he Ruby?” “I’ve nothing to say about Max Kaminsky at all,” responded his interviewee, potentially slamming the brake-pedal on an otherwise fascinating conversation. But with his inexhaustible bonhomie Steve laughed away the remark and Ruby was restored to good humour within a sentence.

But although his secret heart may have belonged in such territory Steve Voce comprehensively covered (and loved) all the wider territories of jazz too. Looking at the copy CDs on my desk I find interviews with musicians as wide-ranging as arranger Ralph Burns and Johnny Mandel (whose prolific songwriter output included The Shadow Of Your Smile, Emily and A Time for Love, and whose multifarious activities as a trumpeter-composer-arranger included film scores and arranging for master craftsmen from Tony Bennett to Manhattan Transfer). Such interviewees (as I know all too well!) present diverse challenges to ensure profitable conversation but Steve could effortlessly cover them all, making friends with his subjects in the process. In the sacred pages of Jazz Journal (which I have begun to re-read since he died) I have begun to rediscover more interviews with acknowledged jazz giants such as Stan Getz (another risky subject) with whom he could immediately find himself on friendly and instantly communicatory terms. (I remember his sombre reflection after Getz died: “They’ve told me that Stan is dead – but I don’t have to believe it if I don’t want to…”) But he could also interview at length (say) a West Coast non-headliner and converse with him on equal terms about every detail of his subject’s career; thereby producing what, in fact, was – and is – invaluable oral history. Someone should find these interviews (Alyn Shipton, where are you?) and gather them into a book. And it’s a great pity that Steve himself was too busy in the world of jazz not to write more books of his own; his works and knowledge would stand close to the definitive writings of American contemporaries like Dan Morgenstern.

Steve belonged with the big men and women in the international world of jazz, had heard the music at its very best, mixed with many of the musicians who made it, and was reluctant to betray his principles

I don’t think there’s any doubt that with the arrival of jazz-rock and fusion Steve saw the beginnings of a twilight for the music he loved. As he said in 1970 (over four decades before he died), “There is little for either music to gain from the other and, as in all compromises, both must lose something.” Having loved his columns in Jazz Journal (also titled over the years “What’d I Say” and “Scratching The Surface”) I was openly distressed to see that his last one was headed “Still Clinging To the Wreckage” – a regretful but unrelenting acknowledgment that, for him, the golden years of jazz were gone. Perhaps it is that – for people like Steve, Alun Morgan, Charles Fox or Peter Clayton – the inevitable progression of jazz finally fetches them up against an unacceptable artistic barrier. And even Humphrey Lyttelton (whose acknowledgement of new developments in the music was unfailing during his four decades of broadcasting The Best of Jazz on BBC Radio 2) wrote in the liner note to his Humph’s Choice CD compilation in millennium year “It’s now ‘standing room only’ on my personal Mount Olympus but new gods are always welcome.” What they would have made of the music of Ezra Collective’s award-winning Mercury Prize in 2023 is anybody’s guess. But I think, regardless of content, they would have at least approved of jazz music once again – however temporarily – rising to the surface of popular culture for a new generation.

I’ve noted in odd (and all too often brief) obituaries for Steve and his writings such variable terms as “witty” (yes) “acerbic” (on occasion) and even on one occasion “reviled”. And although it’s true that, from time to time, he would lay into lesser talents with a hard pen he could also be inordinately generous to his many musician friends on the UK jazz scene (Humph, Bruce Turner and Alan Littlejohn were three random examples of many). In the end however, I think the point is that Steve belonged with the big men and women in the international world of jazz, had heard the music at its very best, mixed with many of the musicians who made it, and was reluctant to betray his principles. In short he was a critic whose artistic terms, rightly, were not for the compromising. But for me he will always be the big-faced, ever-smiling man who was a regular friend when I visited Liverpool or Southport, who loved jazz to his soul and gave his life to it. And what more can anyone do?