“Well, probably, I’m weird!”, joked celebrated Kobe resident and electric bassist Paul Jackson with his signature robust laugh when asked to speculate why Herbie Hancock chose him for his new band in 1973.

Weirdness aside, Hancock knew talent when he heard it. Jackson went on to contribute more than his share to the Hancock sound of that era, beginning with the seminal funk album Head Hunters, which negotiated the fine line between commercial appeal and artistic exploration with spectacular success. The albums that followed (Thrust, Flood, Man-Child, Secrets, V.S.O.P., etc.) confirmed the rare alchemy of this extraordinary group.

Head Hunters: ‘From this came Weather Report, Chick Corea, everybody else – came out of this album right here’

Jackson’s musical journey began in Oakland California where he was born 28 March 1947. Recognised as a child prodigy, he began playing trombone and acoustic bass barely out of knee pants. He went on to gain journeyman experience with every style from Dixieland to Latin while forming musical ties that held for years. Two early associates from the Bay Area were drummers Mike Clark and James Levi. Jackson brought Clark to Hancock’s attention, and Levi supplied percussive power for “Y”, the bassist’s trio at the time of this interview (2009).

In 1985, Jackson moved to Tokyo on the wings of an accomplished career, having worked with many of the greatest jazz, funk and soul musicians ever (Sonny Rollins, Stanley Turrentine, Harvey Mason, Pointer Sisters, etc.). He later settled in Kobe, quickly establishing himself on the music scene in the Kansai region of western Japan.

Paul Jackson remained active until a few years ago when illness curtailed his musical pursuits. Though I have been unable to confirm this, word has it he is confined to a wheelchair and unable to speak, spending much of his time in hospital. On behalf of Jazz Journal, I’d like to wish him well.

The interview took place in January 2009 at the French restaurant Au Limo in Ashiya, where he occasionally played with his trio. A version of the story appeared in the June 2009 issue of Kansai Time Out, an English-language magazine serving the cities of Kobe, Osaka and Kyoto (Kansai region).

The following excerpts come courtesy of Cadence which plans to run the interview in toto. To allow Mr. Jackson maximum space to tell his story himself, I have kept my commentary brief. The order of questions has been changed in some instances.

I began by asking Paul about the original album, Head Hunters [1973]. (He had been referred to Hancock by producer David Rubinson.) Here is some of what he said about the making of the album.

“It’s like very complex simplicity, and we had a good communication thing going. What happened is that on this recording, I had just built the bass and Frankie Terrell and David Rubinson, who was the manager and producer at the time, allowed me to actually set the bass up. Through the mixing board [I had] separate channels for every string. I have a split box for every string.

“I originally started out playing the bass line that we replaced on the synthesizer, but all the songs on here were recorded that way, which was very different. This is the first album, period, ever to use a four-channel bass recording.

“That band was fun. It was a magic thing. It happened. The magic of Chameleon was [that] our engineer Frank [Fred] Catero – that whole thing – was spliced together in three different sessions in two different studios, and he [Catero] matched it right. This is [with] no computers, this is a guy going reel to reel, and matching it beat to beat. They’re all hand-cut splices. This is a master at work”.

Later on in the interview, I asked Paul if Hancock had welcomed input from the other members.

“A lot of stuff would be themes, or a bass line. And most songs were conceived from jamming, and then they were built into what they are. It literally evolved. I mean, we had two, three weeks of intensive practice, and we started from, like, ‘Okay, count it off’. Or I would just play, you know. But a lot of it – Herbie would come up with a melody line. But I was fortunate enough in that band to have always had the latitude of developing my own bass lines. And also I had the latitude of being able to suggest, ‘Hey, why don’t we do this here?’ And we would try it.

“Yeah, sure, it was really open [to suggestion]. We did one little concert series – they got me off of that real fast – where I sat down and played the piano, and Herbie’s playing synthesizer, and the management pulled me off of that one real fast, ’cause I was great. I had a good time, you know, because my pet thing was playing organ, and it still is.

I mentioned that Head Hunters became a huge hit.

Yes, and we had to work for that. We worked that album because it was such a big change from the Mwandishi album [1971], the one that Herbie had originally made. That was closer to Miles, Jack Johnson, Bitches Brew. That’s the first album of this type, period. From this came Weather Report, Chick Corea, everybody else, came out of this album right here – these two albums – right here [Head Hunters and Thrust].

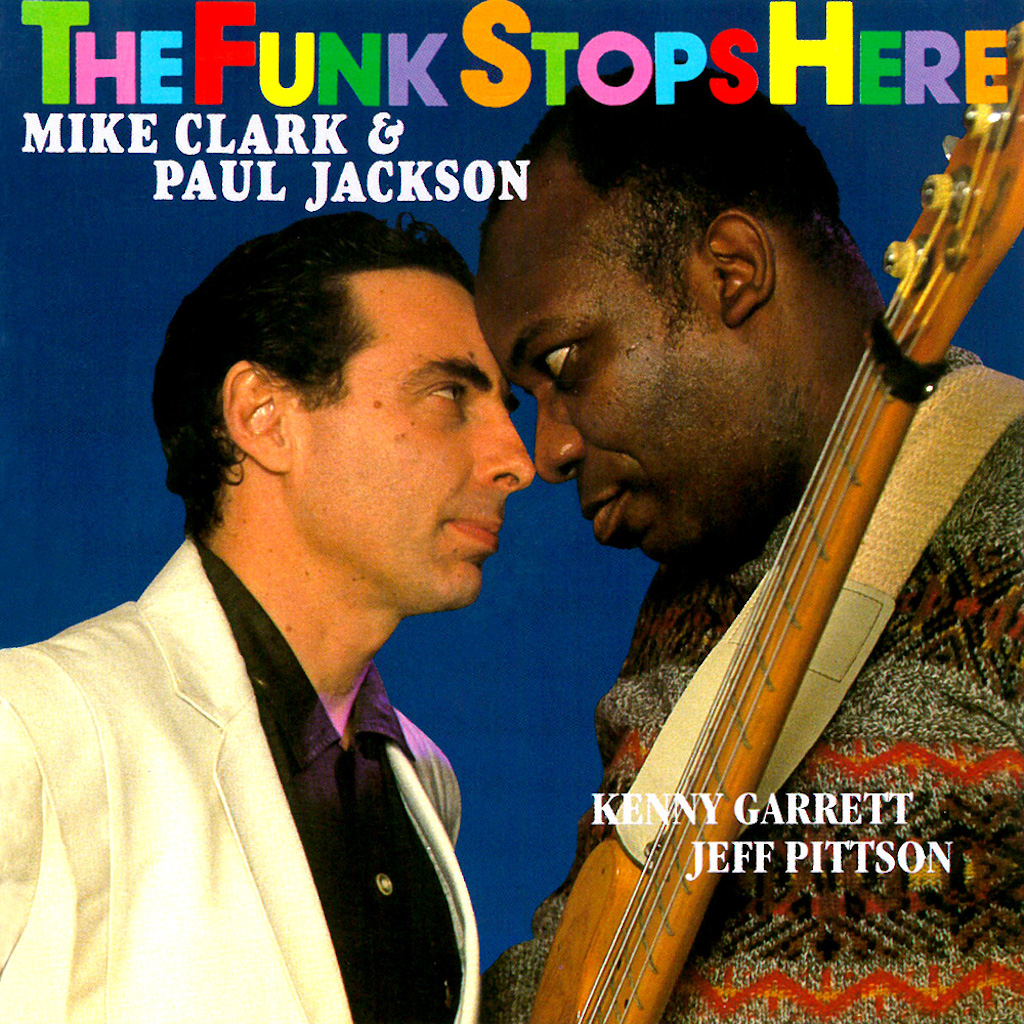

Concerning his association with Mike Clark, who took over the drum chair from Harvey Mason for the group’s second album, Thrust [1974], Paul said this:

“Herbie’s manager at the time was the same [as mine] – I had just finished doing the first Pointer Sisters album. I used to go to their father’s church. David Rubinson said [to Herbie], ‘Hey, why don’t you check this bass player out’. And so I brought Michael Clark over at the same time. Harvey Mason wasn’t gonna make it, and so I just brought Mike because we were living together. I said ‘Come on man, this is our chance, let’s go on in there’.

“I brought him in, and it kind of set a standard, and then I brought in James Levi, after Mike. It got to the point where the kind of respect, they would ask me, ‘Hey, do you think this drummer’s gonna be cool?’ I brought in a lot of really good people”.

Backtracking a bit, I asked about Paul’s early listening and playing experiences.

“My parents played everything [varieties of music]. My father played stride piano, jitterbug, you know, stride kind of music. I learned a couple of songs. He taught me how to play them on the piano. I had a very good music teacher and borrowed the school bass, and I actually used to carry the bass from school. And I practised and I had a natural talent. I started out on trombone.

‘I used to also play with a big band. That’s why I got into the thing of really trying to project, which actually carried over into the sound that I have on electric bass’

“I started getting jobs from the time that I was 12 years old. I was playing with Dixieland bands and I was actually playing with my music teacher in San Francisco and Oakland, playing out on Treasure Island, doing the military clubs and stuff like [that]. The next youngest person in the band to me was 49 [laughs].

“And I used to also play with a big band. That’s why I got into the thing of really trying to project, which actually carried over into the sound that I have on electric bass, which added to the uniqueness of my sound. I recognise that now, there’s a Paul Jackson sound in the way I play. And it’s built from me having to play with big bands and not having an amplifier. Just string bass, and you have to dig in”.