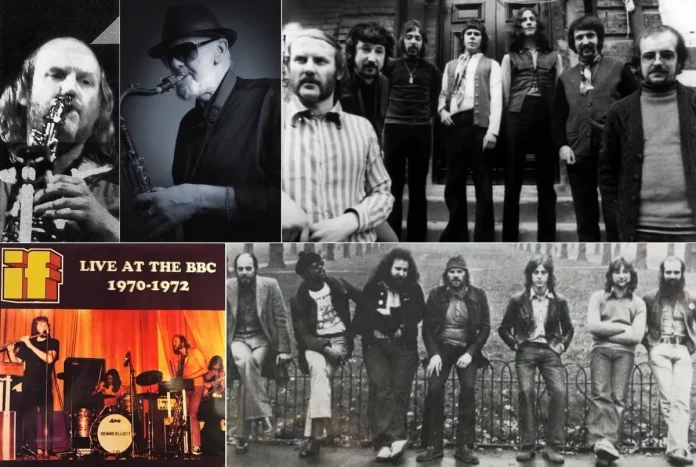

“Quite honestly, in the last year I’ve been playing the best jazz I’ve ever played in my life,” asserts the 84-year-old Dave Quincy, who achieved his greatest commercial success in the 1970s as saxophonist with jazz-rockers If. “I feel my playing has reached the point which I’ve been looking for all my life. It’s a bit late though – I wish I’d reached this point earlier!”

As a musician who has been active since the early 60s, Quincy has experienced a range of musical situations that would be unimaginable for a young jazz musician today, emerging from years in a music college. Early in his career, for example, he toured backing Jet Harris, after Harris had left The Shadows. “The first tour I did with Jet Harris was in 1962 with Sam Cooke and Little Richard, with everybody travelling together in one coach. Jet played lead bass guitar and he was playing good at that time but he had a drink problem. I think that’s why he left The Shadows and as time went on it got worse and his career went downhill, unfortunately.”

Quincy then joined Geraldo’s Navy. “I did work on the boats a little bit. I did the Queen Elizabeth and went to New York and I went to the Half Note Club and saw John Coltrane – the quartet with Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner and Jimmy Garrison. I went up to Coltrane and had a chat with him and he was a real gentleman, a nice guy to talk to.”

Back in Blighty Quincy joined The Thunderbirds, a band that also included future Colosseum keyboard player Dave Greenslade and future country-guitar legend Albert Lee. The band backed Chris Farlowe, whose Out Of Time became a number one hit. “I wasn’t on any recordings he did, they were made with studio musicians, but he was a great singer and we always got a good reaction [on gigs],” says Quincy. “It was great, but I was moving more towards jazz playing and I had begun working with [future If guitarist] Terry Smith. We used to do quite a lot of gigs at Ronnie Scott’s Old Place in Gerrard Street, like Saturday all-nighters.”

Quincy, Smith and future If saxophonist Dick Morrissey all bonded when they found themselves playing in a soul band led by J.J. Jackson. “That was a good band, a 10 piece,” recalls Quincy. “The band was managed by Lew Futterman who said to Dick ‘If you ever want to form a band, let me know. I’d like to manage it.’ And that’s how If came about.”

‘We’d all been doing gigs in jazz clubs in the UK and then suddenly we arrived in L.A. and Capitol Records laid on this Cadillac and held a reception for us in the Capitol Records Tower. That’s how we were introduced to the USA’

If, a septet, first toured America in 1970, early in their career. “It was unbelievable, really,” says Quincy. “We’d all been doing gigs in jazz clubs in the UK and then suddenly we arrived in L.A. and Capitol Records laid on this Cadillac and held a reception for us in the Capitol Records Tower. That’s how we were introduced to the USA.”

The band toured the States extensively. “I remember we supported Ten Years After in Chicago and there were 10,000 people there,” says Quincy. “We did a gig with Elton John in Detroit and a gig at the Fillmore East in New York with Black Sabbath and Rod Stewart. But we were a little out of place. I don’t think the agents or promoters quite knew how to categorise us and that was a problem.”

If also played club gigs in the States. “We played Ungano’s in New York City and Miles Davis and Tony Williams turned up to hear the band! And at the end of the gig I saw Miles walking towards me and I thought ‘Wow, he’s going to talk to me.’ And then suddenly this guy came up and put his arm around him and said ‘Hey Miles, I want to talk to you…’ – and Miles was gone!”

The band were touring America in the hippy era when many of their musical contemporaries destroyed themselves through excessive drug use. Quincy reckons If survived pretty well unscathed. “Nobody in the band had serious problems. Not really. Obviously there were things going on, I can’t deny that. Particularly in Los Angeles there were opportunities. We played the Whisky a Go Go and that was full of crazy people. I remember talking to a girl there and I said ‘What’s your name?’ And she said ‘I’m Spaced-Out Gracie!’ That really sums it up, doesn’t it?”

‘I was always into writing and always enjoyed it. I was influenced by writers like Cole Porter and George Gershwin, a lot of whose songs are jazz standards. I was always thinking about how the saxophone or the guitar could play solos on the chord sequence’

Quincy was If’s main songwriter. “I was always into writing and always enjoyed it. I was influenced by writers like Cole Porter and George Gershwin, a lot of whose songs are jazz standards. I was always thinking about how the saxophone or the guitar could play solos on the chord sequence, I was writing songs that musicians could blow on, like happens with jazz standards.”

If narrowly failed to break through to major success and, after four acclaimed albums, split up in 1972. “Dick Morrissey got ill and the band sort of fell apart,” says Quincy.

Still, he remembers If with satisfaction. “I think we were the only British jazz-rock band to have been signed to an American label, Capitol Records. I’ve very proud of that. But you’ve got to get to the point where you start to make a lot of money otherwise it becomes difficult. That’s the way it works.”

Oddly, Morrissey soon reformed If and recorded three further albums with a new line-up. “Lew Futterman released Terry Smith and myself from our contracts but wouldn’t release Dick. He had to see out his contract so he reformed If and carried on until his contract expired. I haven’t listened to those albums much but it was a very different style to what we were doing previously.”

Following the demise of If Quincy and Smith formed Zzebra with ex-Osibisa saxophonist-percussionist Loughty Amao and others. “The first gigs we did were in small jazz clubs and support work at Ronnie Scott’s for American musicians like George Benson. And from there we got signed to Polygram. I was very interested in Afro rhythms and the first album [Zzebra, 1974] was a combination of Afro rhythms and jazz and rock. But the second one [Panic, 1975] developed in a slightly different, more avant-garde direction.”

Jeff Beck guested, uncredited, on Panic. ‘He’s my idol as a guitar player, a fantastic player and he played rhythm on some tracks. Immediately he started playing you could tell what a fantastic feel he’d got for rhythm’

By then Terry Smith had been replaced by Steve Byrd. “Terry got disillusioned,” sighs Quincy. “The band wasn’t going in the direction he wanted. He wanted to get back into jazz so he wasn’t happy. He said ‘I think I’m going to move on,’ and I said ‘Yeah, OK.’”

Jeff Beck guested, uncredited, on Panic. “He’s my idol as a guitar player, a fantastic player and he played rhythm on some tracks,” enthuses Quincy. “Immediately he started playing you could tell what a fantastic feel he’d got for rhythm.”

Excellent archive recordings of Zzebra have recently been released as Hungry Horse Live In Germany 1975 but the band’s end was already in sight. “It was the era of glam rock and David Bowie and punk and we weren’t getting the work we needed to keep the band going,” says Quincy.

With success and a viable income elusive Zzebra threw in the towel. “I went back to playing jazz,” says Quincy. “I got involved in a Latin jazz band called Semuta. We were signed to Ronnie Scott’s agency and used to support Ronnie Scott’s quartet and we did a few gigs at Ronnie Scott’s club.

“And then I released Groovicity [by Groovicity, in 2014] which I was quite pleased with but unfortunately I became ill, I got cancer. I beat it but it was impossible for me to promote the album so it didn’t achieve much.”

Unexpectedly Quincy put together a new If in 2016, roping in his old partner Terry Smith and releasing If 5. “I think a lot of people were disappointed,” he admits of the album. “They were expecting Terry to play in the style of the [earlier] If records which was quite clever, fast jazz-rock. But Terry’s style had changed and it was more of a jazz-influenced album than jazz-rock. It sold a bit and I was quite pleased doing it because I did quite a bit of writing for it but it wasn’t strong enough to reform the band. We just did the album and that was it.”

Quincy still gigs occasionally, sometimes with Terry Smith. “We’re good friends. We go back to 1964/65 and we’ve always played together. I did two gigs with him recently so I’m still playing. I’m getting on a bit, I’m retired really – but if somebody wants to book me, I’m up for it!”