Most of those of us who became aware of jazz in the 30s or 40s accepted as a fact that Duke Ellington’s work was the apex of our music and that its historic achievements would never be challenged. But they were, and the first attempts to displace Duke’s oeuvre came with the bebop disruption, and, alongside it, the rise of Stan Kenton.

Kenton’s fans never engaged with Ellington in any way, and most probably still don’t. But bebop’s followers, more open-minded, did eventually discover Duke and in varying degrees to acknowledge him. Duke’s committed disciples (for they are such) today are tightly knit and, more so than with any other group of jazz lovers, regard their music as a way of life. The tag “LYM” means “love you madly”, taken from a familiar cliché used by Ellington when addressing his audience, and it serves as a name for the highly-organised and international band of his devotees.

Finesse was one of the words most appropriate to Ellington’s world. Using broad strokes, we can say that he wrote (composed and arranged) the magnificent music, found the perfect people to play it, and gave it a continuity of music and musicians that has ensured that it remains valid to this day. To his many fervent partisans, Ellingtonia has never gone out of fashion.

Symbolic of that continuity are the lines of trumpeters, tenor sax players and bassists who loved his gilded cage.

I’ve chosen here to look at the line of clarinet players that graced his reed section. Actually, like all lines of Ellington musicians, it isn’t very long, for such was the prestige and satisfaction of being in his band that all his great players stayed with him for a very long time and he didn’t need replacements.

None of the established bandleaders and arrangers used the clarinet as comprehensively as Duke Ellington did. It permeated his music and, as long as the wielder of the horn was one of Duke’s half dozen great clarinettists, he could be sure of plenty of solo space. Shaw and Goodman featured themselves as stand-out stars with their own orchestras, of course, but Ellington wanted the instrument to permeate his music and his orchestral use of it was as impressive as his use of the soloists.

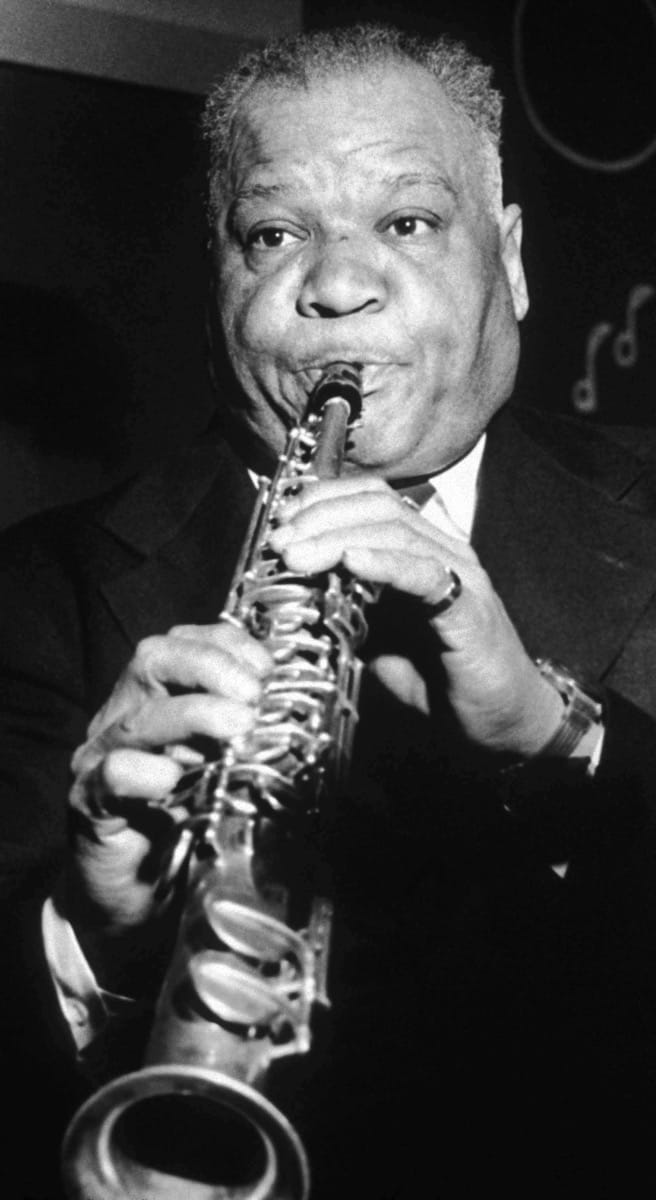

He let his partiality towards the instrument be known as early as 1925 when that summer Sidney Bechet came into the band for an all-too-brief stay.

In his autobiography Duke wrote “Most of the time Bechet played soprano, but now and then he would take out his clarinet. Although it wasn’t really his thing he had the world’s greatest wood tone on that instrument. You don’t hear that wood in what most clarinettists play today, but I love it – and I miss it.

“Bubber Miley and Bechet used to have cutting contests nightly, and that was a kick. They would play five or six choruses at a time, and while one was playing the other would be backstage taking a nip.

“Bechet was never a very outgoing man, yet he took Johnny Hodges under his arm and taught him everything. Johnny’s approach to the saxophone was very much in that direction anyway, so it was easy for him to absorb from Bechet, whom he loved and really idolised.

“Speaking of those two reminds me of when I was writing The New Orleans Suite in 1970. I was writing the portrait of Bechet for Johnny Hodges to solo on when a phone call announced that Johnny had just died of a heart attack during a visit to the dentist.” Despite Duke’s love of Bechet’s work, he never recorded with Duke and no manuscript remains to tell us what Duke had in mind for him.

But Bechet’s influence on Duke remained strong, and in 1932 Duke brought Sidney in as a consultant, notably working with the reed section. Perhaps one upshot of this was that, in the May 1932 Sheik Of Araby by the band, Johnny Hodges replicates Bechet’s standard solo on the tune.

Prince Robinson played clarinet and tenor, and was highly regarded by his fellows. His best friend Rex Stewart, still years away from joining Duke, described him as “an excellent player”. Prince joined the band in early 1925 and worked for Duke over the next two years. There don’t seem to be any of his recordings with Duke in current circulation but he can be heard out of context, soloing with McKinney’s Cotton Pickers on ASV AJA 5518 where he also displays his dextrous habit of soloing on tenor and clarinet on the same track. He swings with grace, easily a match for contemporary Coleman Hawkins.

Harry Carney, sometime clarinettist, had joined Duke in January 1927 although he mainly played baritone in his incredible stay with the band until 1974. Carney had the expected mastery of the instrument and over the years used a soft tone which sounded as though it may have been influenced by Barney Bigard, who himself brought the whole history of New Orleans clarinet into the orchestra.

King Oliver’s was the most distinguished band that Rudy Jackson had played in, being there from late 1923 until the middle of 1924, claiming to have sat next to Buster Bailey in the band. He rejoined Oliver briefly in 1927 before moving to Ellington in June that year. Rudy made several appearances on record with Duke, most notably on the first ever Creole Love Call where he acquitted himself well enough. He also soloed on Washington Wobble and Chicago Stomp.

Rudy was shunted out when another Oliver veteran appeared for consideration in December 1927. When he had visited recording studios until then Barney Bigard had appeared often on tenor (vide Johnny Dodds’s Black Bottom Stompers) where his playing was oftern just this side of lumbering.

“After Rudy Jackson had left we had a band meeting to decide whether to get Buster Bailey or Johnny Hodges,” said Duke. “Buster was regarded as just about the top clarinettist at that time, 1928, but Barney Bigard voted him out and Johnny Hodges in!”

When Barney joined Duke, he set off on the path to become one of the greatest clarinettists of them all (still playing tenor in the section, but never challenging Ben Webster).

See part two of this article

See part three of this article