After World War II a group of (mostly) European “classical” composers began to seek new means of expression. This movement was initially centred in the Darmstadt summer school, and its core members included Karlheinz Stockhausen. There was a feeling that if millennia of European culture had culminated in the Holocaust it was a tradition that should be abandoned and replaced. Stockhausen wrote “an epoch which had started hundreds of years ago, even 2,500 years ago with the way of thinking of the ancient Greeks, had finished during the last war.” In Germany the concept of “Stunde null” (zero hour) appeared, suggesting the opportunity for a new start.

In the jazz realm the experiences of Afro-American soldiers sent to Europe in World War II enabled them to compare their treatment there with that meted out back home, and would eventually lead to more intense challenges to racism expressed through, inter alia, free jazz, with overtly politically engaged artists such as Archie Shepp spearheading the movement. Alongside these were the less directly political, more spiritually oriented innovators like Albert Ayler and John Coltrane, who looked for a different route to the future.

In both continents the Vietnam War acted as a stimulus to radical impulses in the arts, but European movements were generally more left-wing than those in the US. Also, free improvisation in mainland Europe and Britain began to be distinguishable from most American free jazz, which, as many of its exponents insisted, was firmly rooted in the collective improvisation of early jazz. The European variety was arguably no longer jazz at all.

Probably the most significant figure in that European movement is Peter Brötzmann, who has been associated with the FMP label since its inception. He has said: “All we talked about was how to get rid of the old structures,” paralleling the aims of the Darmstadt school. “I never thought music was a healing force of the universe. I didn’t agree with Mr. Ayler. But we wanted to change things, we needed a new start. In Germany, we all grew up with the same thing: ‘Never again.’ But in the government, all the same old Nazis were still there. We were angry. We wanted to do something.”

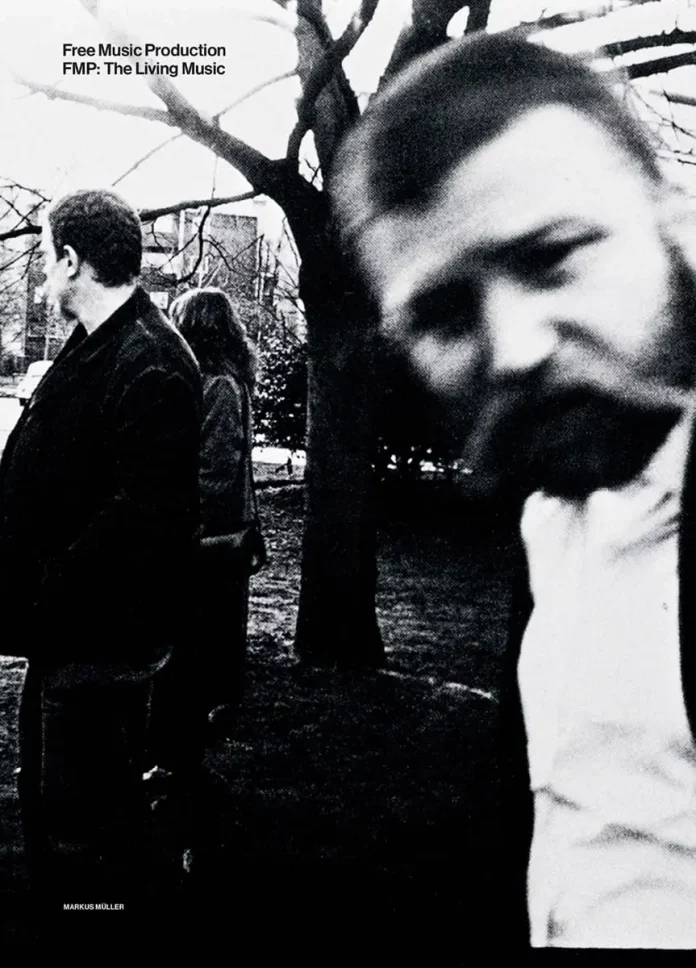

One of the ways this generation found of doing something was by establishing the FMP label and organisation, and Müller’s book is a monumental celebration of both. I must call into play the cliché “weighty tome”. The book’s 400 pages, plus fold-out cover, could outbalance several bags of sugar. They overflow with illustrations: reproductions of record sleeves, press cuttings, events posters and leaflets, with pictures of exhibitions and shots of musicians, many in performance, and many full-page (34 x 24 cms) or double-page spreads.

In addition to Müller’s informative commentary on the history of FMP and a piece on the Total Music Meeting (which, like FMP, developed from the New Artists Guild) there are interviews with and statements by several major figures associated with FMP, including Irene Schweizer, Hans Reichel, Peter Kowald, Paul Lovens, Louis Moholo and Brötzmann as well as a substantial essay on Cecil Taylor by Diedrich Diedrichsen. The book should satisfy all but the most train-spotterly fans and students of the genre and, given its weight and sumptuousness, its price is very reasonable.

Free Music Production – FMP: The Living Music by Markus Müller. Wolke Verlagsges Mbh, 400 pages (illustrated), pb, £30.95. ISBN 978-3-95593-128-5