It has always seemed that jazz has had far more than its share of musicians who died young.

Leon “Chu” Berry died at 31, joining a list that included Bix Beiderbecke, Bunny Berigan, Jimmy Blanton, Charlie Christian, Eddie Costa, Herschel Evans, Wardell Gray, Billie Holiday, Hot Lips Page, Charlie Parker, Bessie Smith and Lester Young. Just imagine the wonderful music that we’ve missed because of those deaths.

Had there not been a Coleman Hawkins, Berry would easily have been the standout swinging musician of the 30s. He would have dominated the scene until the Lester Young tsunami hit. His outstanding natural swing merited that misused word unique. Although he led his own groups in the recording studios, he was essentially a sideman, and few of the musicians he worked with were possessed of similar natural talent. His work adorned a multitude of jazz classics, from Bessie Smith’s Gimme A Pigfoot to Teddy Wilson’s Blues In C Sharp Minor and he was shown deep respect by the other musicians when he worked in bands such as those of Fletcher Henderson and Cab Calloway.

In recent years Calloway’s reputation, for decades dismissed as irrelevant to jazz, has been pretty well restored. Cab led some of the finest big bands of the 30s and 40s and even if his most admirable quality was leaving the men in his band to get on with running it, he deserves credit. When he chose not to indulge in the inanities demanded of him by the public, he was a good singer. Cab also treated his musicians better than any other leader did – during the 40s his sidemen had a month’s holiday and a $100 bonus each year. Those bands produced a multitude of second-rank jazz players of great worth such as pianist Bennie Payne, trombonists Claude Jones, Tyree Glenn, Quentin Jackson and Keg Johnson, drummer Cozy Cole and trumpeters Mario Bauza and Irving Randolph.

The giants were Dizzy Gillespie, Milt Hinton and tenorist Chu Berry.

Born in Wheeling, West Virginia on 13 September 1908, Chu, still a schoolboy, idolised Coleman Hawkins. He had begun playing the alto at high school and persevered with it for five years, changing to tenor at the end of that time when he first heard Hawk during one of Hawk’s early tours. Certainly Chu played the larger horn by the time he travelled to Chicago to join the big band led by Sammy Stewart, by which time he had begun picking up Louis’s innovations second hand from Coleman Hawkins. Hawk had of course sat next to Louis Armstrong in the Henderson band when he joined it in 1923 and hadn’t missed the chance to absorb all the new things coming from that beacon of musical light.

It was around the time that Chu was with Sammy Stewart’s band that a film came out featuring a character called Chu-Chin-Chow. He bore a resemblance to the tenor-playing Chu, who had a large build and athletic frame, topped by a smart moustache and goatee beard that no doubt inspired his nickname.

In 1930 Chu went with the Stewart band to play at New York’s Savoy Ballroom. He liked the city and, seeing the opportunity for lots of work, decided to stay there, finding work with many established bands.

By 1932 Chu was with Benny Carter’s band, and it was there that he made his first records. The names on the date confirm that Chu had moved into the first division. They included Frankie Newton, Dickie Wells, Teddy Wilson and Sid Catlett. On 10 October 1933, still with Carter, the two men recorded with the Chocolate Dandies, Chu taking Hawk’s place in the ephemeral group. The two also starred in the Spike Hughes jam sessions recorded specifically for issue in England.

Leaving Benny later that year he joined Teddy Hill for a couple of years before Hawk did him a back-handed favour by leaving for Europe in 1934, staying there for five years and giving Chu the chance to take over the tenor scene back in New York.

In retrospect we can see that Berry’s solos were like a text book of swing. He loved riffs in his improvising and it seems probable that he was a big influence on swing’s arrangers and composers

One quality that Chu had in abundance was consistency, and he never seemed to have any bad days. He’d developed a powerful swing, and had become such a driving player that that aspect of his playing obscured his gifted ballad playing, which was eventually only displayed on a few classic records like Cab Calloway’s 1940 Ghost Of A Chance. As far as swing was concerned, in retrospect we can see that Berry’s solos were like a text book of swing. He loved riffs in his improvising and it seems probable that he was a big influence on swing’s arrangers and composers. Certainly his bands jumped and his colleagues swung whether they wanted to or not.

He found an ideal partner on and off record in the young trumpeter Roy Eldridge, a flashy and brilliant technician of the trumpet who added fire to Chu’s recordings and was able to keep up to speed with the tenor player.

It’s not clear where the two first met, but they were both members of the Teddy Hill band when it recorded in 1934. Roy remembered: “Me and Chu used to get off work at three or four in the morning and we’d play until perhaps one that afternoon. We never seemed to get tired. Many a time I’d get out of bed, get dressed and go out again. It seemed like I never put the horn away.”

Only one track was recorded by the Carter band with Chu in 1932 and I haven’t been able to hear it. Effectively the explosive start to his record career is with the Chocolate Dandies and four tracks – Blue Interlude, I Never Knew, Once Upon A Time and Krazy Kapers – from 10 October 1933. An early mixed band, this featured Carter, Berry, Floyd O’Brien, Teddy Wilson and Sid Catlett. This was very polished and progressive music for its time and Chu, just turned 25, already displays as a giant.

The tracks appear on ASV CD AJS 276 under Carter’s name, and are preceded by Carter’s March 1933 Swing It, where a confident if not authoritative Chu takes eight bars at the end of the track.

A month later Chu took part in a most remarkable and immortal session that produced Bessie Smith’s last four recordings (Do Your Duty, Take Me For A Buggy Ride, Down In The Dumps and Gimme A Pigfoot). This mixed the singing of the Empress from the 20s with the playing of the top musicians of the 30s (Frankie Newton, Jack Teagarden and minimally Benny Goodman. The obvious success of the music confirmed a new start in the singer’s career but, in a horrible precursor to Berry’s own death, Bessie was killed in a traffic accident).

I have the 10-CD Columbia Bessie Smith, but this is overkill. You might like to gamble on The Absolutely Essential three-CD set which at time of writing is £4.99 on Amazon. This session should be on that.

Roy and Chu along with Benny Goodman, Jess Stacy and Israel Crosby recorded as Gene Krupa’s Swing Band in a sensational session on 29 February 1936. It was collected in 1995 on Roy Eldridge: Heckler’s Hop (Hep CD 1030) which also included four tracks by Chu Berry And His Little Jazz Ensemble (Sittin’ In, Stardust, Body And Soul and 46 West 52). Four weeks later Chu joined Fletcher Henderson (he’d earlier had a short time in the band) and stayed for more than a year. Fletcher’s recordings were sparse at this period, but Chu made hay on the 20 or so tracks that feature him (featured on the three-CD A Study In Frustration on Poll Winners PWR 27380). One of the tracks was Berry’s own composition, Christopher Columbus, which was transformed into Sing, Sing, Sing as it became the high point of the famous Goodman Carnegie Hall Concert of 1938. Fletcher Henderson was full of admiration for Chu: “He’s one of the fastest, most inventive and creative minds that has ever been in my band.”

Teddy Wilson’s piano-playing and band-leading seems to be out of fashion at the moment and yet he was a major figure of 16 January 1938. He was a key man in the structure of the music of the 30s who displayed more good taste than any other swing player. There’s a most satisfying five-CD set, available as singles, on Hep CD 1012 to 1035. Our concern is with Vol. 2 (CD 1014) because it contains among its 20 classic tracks two heavyweight classics in Blues In C Sharp Minor, a most unusual composition of Wilson’s, and his Warmin’ Up, both graced by super Chu Berry solos. Mary Had A Little Lamb and Too Good To Be True completed the 14 May 1936 session, and the splendid band also included Roy Eldridge, Buster Bailey, Israel Crosby, Sid Catlett and guitarist Bob Lessey.

While with Henderson Chu inaugurated his Stompy Stevedores on 23 March 1937. The band included Hot Lips Page, Buster Bailey, Fletcher’s brother Horace and Israel Crosby and it recorded four titles.

Chu joined Cab Calloway’s band in August 1937 where Cab regarded him as a god and gave him the ultimate platform for his solos. Chu also acted as an adviser on band matters and was held in similar awe by most of the sidemen. Chu must be given major credit for the high quality of the band. It was a superb surrounding, and when the time came on 10 September he was happy to enlist his second Stompy Stevedores (including the under-rated Benny Payne on piano) from within the Cab Calloway band (Chuberry Jam, Maelstrom, My Secret Love Affair and Ebb Tide). It was whilst with Calloway that Chu made his best recorded improvisations for RCA Victor. These included the two amazing quintet sides, Shufflin’ At The Hollywood and Sweethearts On Parade. RCA also set up three sessions in 1938/9 led by Wingy Manone, which produced admirable results.

On 21 September 1941, Cab had cause, backstage, to raise his fist to his trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. Gillespie swiftly drew a knife and lashed out. The efforts of Milt Hinton to stop him diverted the blade to Cab’s backside, which required 10 stitches to restore it. Dizzy was fired.

A month later, on 27 October, Lamar Wright, Andy Brown and Chu were driving to Buffalo when Andy Brown fell asleep at the wheel. The details are recounted in Alyn Shipton’s biography of Calloway, Hi-De-Ho (Oxford). While the other two escaped injury, Chu was in the front seat and was seriously injured. He was rushed to hospital in Conneaut, Ohio, where he died that evening.

He had been a major figure of his times and with his advanced harmonic knowledge had influenced the playing of both Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, both of whom he’d played with at Minton’s Playhouse. (Parker called his first son Leon, after Chu).

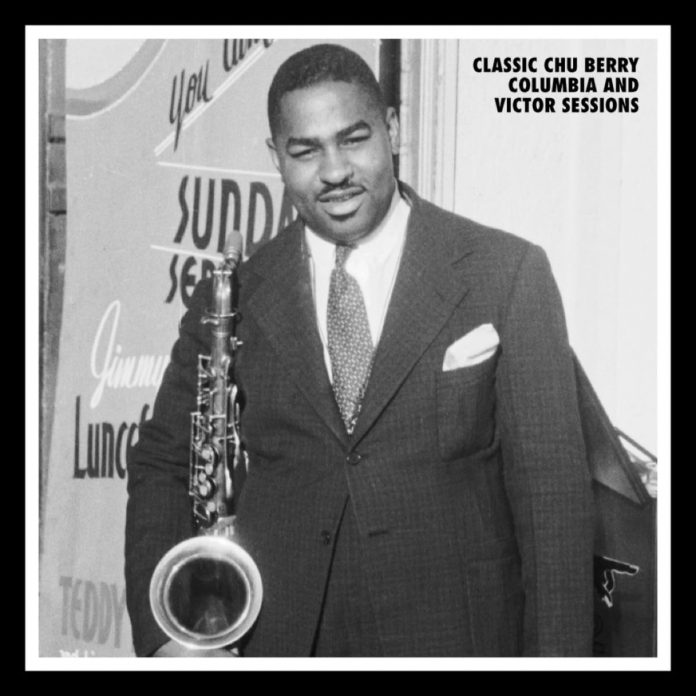

Despite the CD details I have given above, the ultimate way of acquiring a Chu Berry collection is via the Mosaic set Classic Chu Berry Columbia And Victor Sessions (MD7-234) which is an exhaustive collection notably documenting all Chu’s Cab Calloway recordings (including the outstanding and unique 1940 ballad performances Ghost Of A Chance and Lonesome Nights).