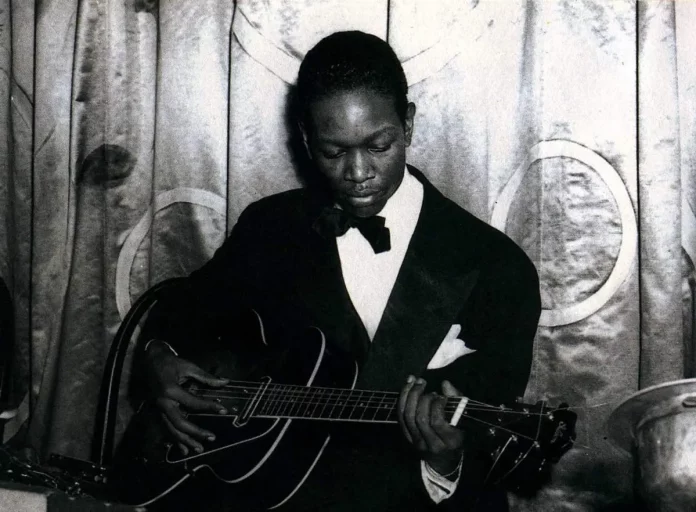

Charlie Christian’s short life was made up of contrasts. He was an Oklahoma country boy from a needy family. In urban New York eyes were drawn to his clumping boots and from there on upwards his clothes were without any style. But the music he made on the electric guitar and the method of playing that he developed for the instrument were to lead and influence guitarists the world over to this day.

Christian’s family, whilst impoverished, was musical, and earned its living playing in the streets. His father was a blind country-style guitar player and singer, and Charlie began life leading him around the Deep South Oklahoma City where the family lived in a rundown wooden tenement.

Christian was one of the earliest musicians to be influenced by yet another giant, Lester Young, who, when they first met, had only recently switched from alto sax to tenor. In 1931 Young had joined the Thirteen Original Blue Devils and was on tour with them when he encountered Charlie in Oklahoma City. Charlie certainly played with Lester during this time, although it can’t be said that the two played together in the Blue Devils. The young guitarist worked as often as he could with visiting bands, and it was in this way that his reputation spread amongst musicians.

Eddie Durham, a Basie trombonist, had experimented with electric guitar as his second instrument, planning to use it in big bands where, unlike the acoustic guitar, it could cut through and would not be drowned out by the brass and saxes. Although detail is short, Durham and Christian became friends in Charlie’s home town, and Eddie passed on his knowledge to the younger man. As a result, single-line electric guitar came to be one of the important big band voices. More importantly, Charlie was at the centre of the foundation of the modern jazz that was beginning to supplant swing at the end of the decade. Charlie was to develop his style based on linear voicing rather than chordal, and didn’t regard rhythm section work as his priority.

Charlie had the briefest of careers, and it’s fortunate that his two-year period in the recording studio is well documented. Not much else survived, and the best writing about him is Dave Gelly’s lengthy essay in the book Masters Of Jazz Guitar (Balafon 1999). Here’s a typically perceptive fragment from it:

“Charlie’s appeal as an artist went beyond mere novelty. He was one of those rare individuals who seem somehow to be made out of music. The lines that flow from him with such grace are like the flight of birds, free and unforced, emerging without any apparent effort. Yet every note is minutely judged, every phrase has a rhythmic charge and turns at some harmonically apt point. And the sheer, unhesitating precision of his playing is a wonder in itself.”

Benny Goodman, a musical hero of similar stature, judged Charlie by his rural appearance and chose to ignore him when they first met. Goodman was by then beginning to be disenchanted with his brother-in-law John Hammond and his interference in the running of Benny’s band. Hammond had assumed unrealistic powers over many jazz musicians, including Goodman and Basie. His influence was such that when Rex Stewart declined to play for one of Hammond’s charities, Hammond was able to have the cornettist blacklisted, and Rex could not find any work in New York for the next two years.

But it was Hammond who, using Benny’s money without the clarinettist’s consent, found Charlie in Los Angeles and had him flown to Los Angeles where Goodman was playing. After one look on their first meeting, Goodman completely ignored Christian. That evening Hammond set Charlie up, amplifier at the ready, before Benny arrived for the quintet’s gig. When he saw the guitarist Benny was furious, but could hardly throw Charlie off the stand – immaterial because, once he heard the guitarist play, Goodman snapped him up and Charlie became the main voice on several subsequent sextet recordings. (Benny featured Charlie on only two of the big band’s recordings – Solo Flight and Honeysuckle Rose, although he played with the big band on stage).

It was in late 1939 that Charlie Christian began appearing on Benny Goodman’s recordings and broadcasts. It was probably with Goodman that Lionel Hampton first encountered the guitarist, and he swiftly co-opted Charlie for a couple of his own small-group recording sessions (including the one on 11 September that housed the greatest saxophone section outside the Four Brothers, comprising Benny Carter, Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster and Chu Berry). Hampton used Charlie acoustically as a rhythm section player. But it was the Goodman sextet with the amplified guitar as a third solo voice, also blending perfectly to make a polished ensemble voice with the clarinet and vibes, that raised all ears.

At the time Charlie joined him, Benny suffered severely from sciatica and had to have urgent surgery so, as the band continued without him, he was unable to exploit Charlie’s talent. When the band had no gigs or finished early in New York, Charlie discovered Minton’s club and began playing there after hours, confidently squeezing in between proto-boppers like Parker and Monk to lead the way in the long melodic adventures of his that had begun, for the first time in jazz, to flow easily over bar lines. The few amateur recordings, so vitally important in jazz history, from these sessions are driven by Christian’s burgeoning and continuously eloquent solo lines, his imagination apparently inexhaustible and his solos, still, 80 years later, sounding as fresh as they must have done when Thelonious Monk and Kenny Clarke tried to adjust to his playing. Having laid down so much guidance, Charlie was unable to follow through as he was at first laid low and then killed by the tuberculosis that had developed back in his Philadelphia days.

Charlie had but a year to live as, half way through his two-year recording career, he took part in the exquisite Profoundly Blue session under Edmond Hall’s leadership for Blue Note on 5 February 1941. The group was sparked by a rare appearance away from the Ellington band by baritone saxist Harry Carney. Ed had played baritone regularly throughout his early career, and it may be this that led to his friendship with the amiable Carney. Another unusual aspect was that Meade Luxe Lewis played celeste throughout the gig. This was also an occasion on which Charlie, perhaps at Ed’s request, played without amplification throughout the session.

Charlie didn’t take care of himself, and all-night revelry, sparked by the fact that he was a 23-year old earning about $250 a week, was his way of life. His tuberculosis, which had lain dormant, returned in June 1941 along with the two social diseases he had acquired in recent years. He was admitted to the Seaview Sanatorium on Staten Island where he slowly began to improve, but he was impatient and one night absconded from the sanatorium with some of his pals for a night of boozing. He had no resistance, and, as a result of his adventure, died on 2 March 1942.