There has always been difference of opinion over the merits of Louis’s playing in the 20s and his more expansive work from the early 30s onwards. Collectors have disagreed with each other when making that comparison between early and later Louis.

The Hot Five/Hot Seven period was one of the most profound in that it was fundamentally creative and was moving the whole body of jazz music in a progressive way. From the 20s onwards, Louis was concerned with developing his playing and style as an individual soloist. The spectacular results were far advanced from his work with Johnny Dodds and Lil Hardin.

It makes no sense to make a rigid comparison between the two periods or, indeed, with the 40s and 50s when Louis, having set the direction of jazz by becoming its most potent influence, expanded to the point where, as he put it himself, he had never played better in his life.

The war years had been both good and bad for jazz in general, and Louis’s recording career was not excepted. The selection of his material was largely taken out of the his hands and as a result he made less distinguished recordings during the wartime era.

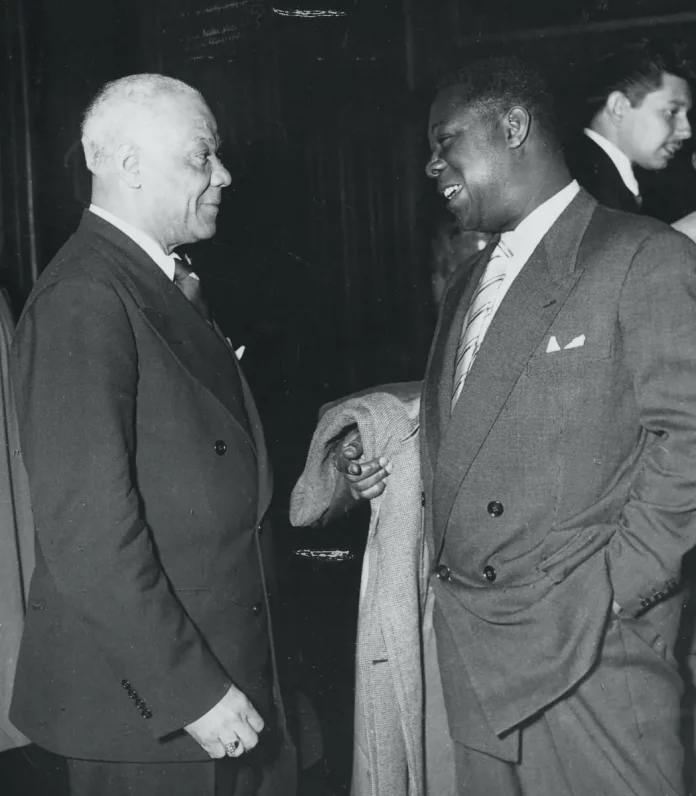

Some of the ones that were outstanding were also controversial. On 27 May 1940, before the United States’s decisive entry into the war, Decca reunited Louis with his off-and-on rival Sidney Bechet to produce four sides – 2.19 Blues, Perdido Street Blues, Down In Honky Tonk Town and Coal Cart Blues. The four titles harked back in style to the last time the two men had played together in 1924. The general thought amongst critics was that because of mutual jealousy the two men felt a coldness towards each other and generally did not get on. Neither Louis nor Sidney ever said anything to confirm this suggestion, and the discord was probably at best invented by fans or at worst was a very minor and irrelevant one.

Armstrong and Bechet both played at their best on the session and interlocked perfectly wherever necessary. The two were such giants that the standard of their backing group, including Benny Morton and Luis Russell, came to be of no importance and the drumming of the great Sid Catlett, always distinguished wherever he played, was the only element of insignificance outside the work of Louis and Sidney. Richard Havers wrote: “It did not work. Perdido Street Blues, probably the best of the bunch, shows what was lacking from Armstrong records during this period – it’s pedestrian and it plods. There’s little or no swing to be heard, even from Louis.”

This was the dominant thought from critics at the time, although many fans, this writer included, cherished the almost romantic reunion with Bechet. Maybe the lack of atmosphere in the four tracks was the result of the cautious enmity that had always existed between Louis and Sidney.

Sidney had agreed to play with Louis in the Town Hall concert of 17 May 1947 that was planned by promoter Ernie Anderson with the assistance of Bobby Hackett. Others chosen to appear, apart from Hackett himself, included Jack Teagarden, Peanuts Hucko, Dick Cary, Bob Haggart, Sid Catlett and George Wettling. The presence of Teagarden at that concert became a wonderful asset when the personnel of the first All Stars came to be chosen. There was a strong movement to choose Kid Ory as the trombonist. Talented in his own traditional field, Ory would have been a limiting disaster in the All Stars.

The concert produced one of the best live jazz recordings ever, available on Louis Armstrong: The Complete Town Hall Concert 1947 on Fresh Sounds FSRCD 701.

Ricky Ricardi points out in his absorbing notes to go with Mosaic’s issue of the concert (Columbia And RCA Victor Live Recordings Of Louis Armstrong And The All Stars – MD9-257, also to be found on French RCA ND89746) that Armstrong is at the centre of the entire show from start to finish. “After the birth of the All Stars Louis always made a special point to feature his sidemen, though he’d always find a way to play or sometimes sing on those features. But at Town Hall Louis only takes a break for three minutes and 30 seconds during Teagarden’s classic version of St James Infirmary. Other than that he is front and centre on 19 of the 20 surviving tracks.”

Although it’s presumed that Anderson recorded the concert, it’s not known how many numbers there were, and it seems likely that some were lost. No matter, what survives is inspired and timeless with each man playing his role to perfection.

In addition, the Complete Louis Armstrong Columbia And RCA Victor Studio Sessions 1946-1966 on Mosaic MD7-270 should be in your collection for it includes Louis Armstrong Plays W C Handy, Plays Fats and a multitude of classics from the period.

- See part one of Steve Voce’s survey of Armstrong’s all-star bands – from the Hot Fives and Sevens to the New York City Hall concert of May 1947.

- See part three of Steve Voce’s survey of Armstrong’s all-star bands – the role of Ed Hall, Jack Teagarden, Earl Hines and others.