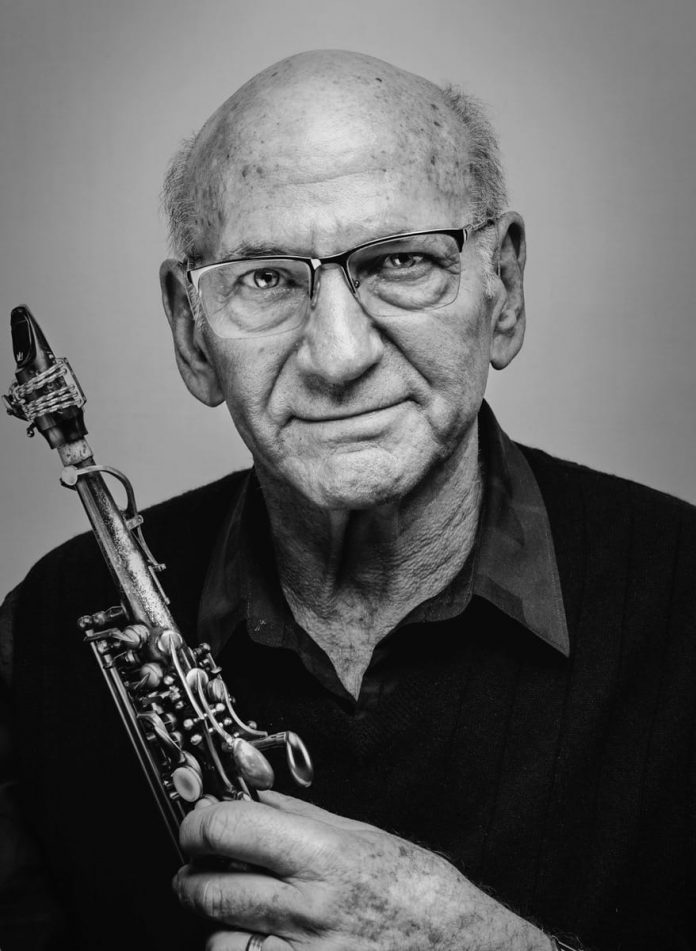

“There was a very high level of musicians involved. It doesn’t get much better,” enthuses veteran soprano and tenor saxophonist Dave Liebman of his latest album Quint5t, which he recorded with an all-star band comprising Randy Brecker (trumpet), Marc Copland (piano), Drew Gress (bass) and Joey Baron (drums).

“I’ve been playing with Randy and Marc for over 50 years, so there are serious roots in the band and I think you can hear that on the recording.”

Liebman explains how he introduces a composition to the band: “With musicians like this you don’t have to say much. In fact, you don’t want to say much because you want to see what happens spontaneously.

“But sometimes it is necessary to say a few words. Like Child At Play is about my daughter. She got out of school and was running like crazy and it was just a joy to see a child – my child – at play. So I might tell a little story like that. And the tempo, of course. Then you run it through and if there’s anything needs cleared up you take charge. But usually with guys like this, the first thing that happens is the best.”

Liebman became a John Coltrane devotee as a young teenager, watching him, transfixed, in New York clubs. He admits that initially much of Coltrane’s music seemed impenetrable. “The first night I saw him was at Birdland. I was 15 years old,” he recalls. “You don’t have enough time to make an analysis of what’s going on – which I couldn’t have done anyway – but the thing that completely transforms you when you listen to Coltrane is the power and the sound.”

With Miles Davis: ‘I didn’t enjoy the music that much … I didn’t think he knew what he was doing sometimes, just letting everybody vamp … I did lament that I hadn’t been there 10 years earlier – in other words, playing real jazz!’

At a Village Vanguard gig years later Liebman spoke to Coltrane. “Trane was [standing] with Pharoah Sanders who recognised me because I was frequently visiting and playing, or trying to play, in the lofts in New York. And he said ‘Show us something.’ I played a couple of notes and that was it. But now I was in the circle! Someone asked Coltrane ‘How’s it going tonight, John?’ Meaning, ‘How’s the music going?’ And he said ‘Weeelllll,’ in that Southern drawl he had, ‘it goes better at home!’ So unpretentious, so direct.”

Liebman’s first significant pro gig, at a time when he had been working as a substitute schoolteacher, was with the brass-rock band Ten Wheel Drive. “That band got me out of the straight world,” he says. “The singer Genya Ravan was great. She was sexy and she knew how to put a song over and get an audience on her side and a lot of the songs had eight-bar tenor solos so whatever improvising there was, I did.”

Subsequently Liebman played with former Coltrane drummer Elvin Jones. “To play with your idol was intimidating but great fun and a great experience. And Elvin had such a sense of humanity. He made people feel good.”

After playing on Miles Davis’s funk and avant-garde-influenced On The Corner album in 1972, Liebman joined Miles’s band. “That was like graduate school,” he smiles. “But I didn’t enjoy the music that much. I did lament that I hadn’t been there 10 years earlier – in other words, playing real jazz!

“I didn’t think he knew what he was doing sometimes, just letting everybody vamp. But years later I wrote the liner notes for [a reissue of the 1974-recorded] Dark Magus and listened to the music and, you know what, it was pretty heavy.”

Davis, of course, seems to have been a terrifying character. “He could be difficult,” acknowledges Liebman. “He was a man’s man with all that that meant in that day and age with women, but I got along with him. And he could be magnanimous. I broke my leg in 1980 and [Miles rang] and said [and here Liebman affects a Miles-like rasp] ‘Do you need any money?’ Because when musicians aren’t working they’re not making money. And he said ‘Get in touch if you need help.’ So, he could be a jewel too.”

Many of Liebman’s heroes, including Miles, Coltrane, Elvin and Charlie Parker, were undermined by hard drug addiction. “Before my period everybody wanted to be Charlie Parker but privately he was saying ‘Don’t do what I do, do what I play.’

“With our generation, which came out of the 60s, there was a lot of experimentation: everything from yoga to eating only rice and vegetables, which I did for a year, to chanting … I tried Scientology because it looked interesting, which it was, but also ridiculous. I didn’t have a problem with drugs but I definitely did see some of my associates succumb to negative forces.”

‘With our generation, which came out of the 60s, there was a lot of experimentation: everything from yoga to eating only rice and vegetables, which I did for a year, to chanting … I tried Scientology because it looked interesting, which it was, but also ridiculous’

One of Liebman’s key early bands was Lookout Farm. “We played everything from Sly Stone to James Brown to Coltrane to blues. At that point my generation, in a three-hour hangout, could have listened to the Beatles, Bartók, Ravi Shankar and Coltrane. And the next day it could have been Jimi Hendrix, Bill Evans and an Indian flute player. So Lookout Farm’s music was very eclectic, from jazz to rock to world music.”

In recent years one of Liebman’s regular bands has been Expansions, which comprises young musicians. “We play standards and the way they look at them is completely different than me,” he explains. “Sometimes I have no idea what they’re doing but I think it’s incumbent that a musician like me plays with young musicians: for them it’s good because it’s expanding their horizons and for me it’s good because it makes me have to come up with something different to fit the way they look at music.”

With Expansions Liebman recently released Earth, thus completing a four-album sequence that began in 1997, with each album named after an element. “I think it’s a great record,” he declares. “I like it a lot. It has interesting melodies and interesting sounds, electric and acoustic, and basically it’s a plea to stop poisoning the planet, which we’re all guilty of.”