“Why do you marry all these beautiful women?” the lady interviewer said to Artie Shaw, veteran of eight such marriages.

“Do you think I should marry ugly ones?” he asked.

Shaw believed that these were not marriages, but affairs. “You couldn’t buy a house and live together in it at that time if you were not married.”

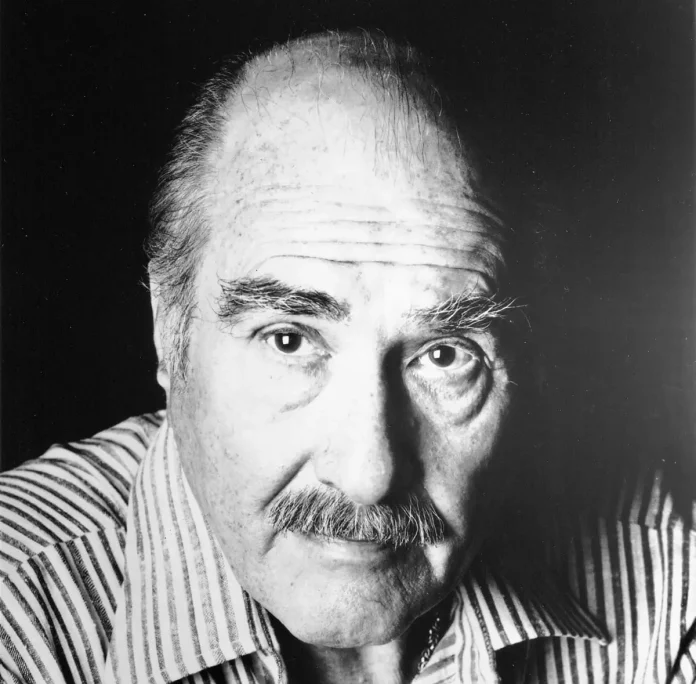

Artie Shaw was one of the most intelligent and controversial jazz musicians of his time. He was undoubtedly the most gifted of the jazz clarinettists (there we are, controversial already).

Two factors spring to mind at once as important elements in Shaw’s development. The first arose when, as a young alto player, he applied in the summer of 1925 to fill a vacancy in the band of Johnny Cavallaro. Cavallaro was impressed with Shaw’s improvising, but quickly discovered that his sight reading was hopeless.

Artie recalled saying: “Can you keep the job open? Give me a month.” He claimed to have been back at the end of that month as a good sight reader. Cavallaro remembered the interval as being six months.

Shaw stayed with Cavallaro for a couple of years, taking up the clarinet after a year with the band because Cavallaro needed one. He found the instrument difficult to master after the alto and when the band got back to New York, he was fired. But at least he was now an experienced reader. When he had his own band he wrote a lot of the book himself, and went on doing this until he retired.

The other factor was less complex. His earliest big bands appeared on stage with just one mike for the whole band. Initially Artie was blown down by the brass and saxophone sections but in response he developed a powerful volume in his playing and remained one of the most muscular clarinettists throughout his career.

“Artie Shaw was a hell of a clarinet player,” said Benny Goodman. “My time was always more legato than his, but his sound was more open. It carried a lot farther. He knows his instrument well, has extreme development in both registers and an amazing harmonic sense.”

Either Benny had much respect for Artie or, being Goodman, he couldn’t be bothered with being catty. He didn’t react on another occasion when Artie walked over to him and said: “You know, if you keep practising, you’ll get to be as good as I am.”

It was in 1938, when the clarinettist first signed for Victor, that the good stuff began. There are the odd items of merit by the bands before that, but on 24 July of that year Shaw’s first recording was Begin The Beguine. The second was Indian Love Call. Beguine in particular, with its fine arrangement by Jerry Gray, became an immediate hit. Writing in this magazine in September 1969, the doleful Owen Peterson said: “It’s difficult to imagine what all the fuss was about . . . I suppose that, by the rather undemanding standards of the time and circumstances it swung well enough . . .” The track, regardless of its standing as a hit and Gray’s superb chart, has typically poised and mellifluous clarinet from the leader. Peterson, in a two-part piece of roughly 5,000 words, did indeed damn himself with faint praise.

Jazz Journal has, however, been good to Artie over the years, with notable pieces by Rod Soar (whose phone interview with, as always, a most articulate Artie was transcribed for November 1987), a long two-part interview (April-May 1994) done at Artie’s home by Jim McLeod at some considerable cost to Jim’s well-being – “He gave me an awful time on the phone . . .” and a six-page piece by Edmund Blandford in March 1998. Blandford’s piece is particularly interesting since it deals with Shaw’s horrendous period with his wartime US Navy band – a group that never recorded. Shaw’s time with the band in the Pacific lasted through most of the war years until Artie’s health collapsed and he and his drummer Dave Tough were sent home and discharged from the navy at the same time.

Artie’s career in music during the 30s and 40s became unstable and he frequently caused great disruption by walking away from it without notice. It has to be said that his earliest bands, the pre-RCA ones, were often not very good, not infrequently with dead rhythm sections. And Artie’s clarinet technique was still developing – he had not yet become familiar with the upper reaches of the higher register, an area of development that he was to make uniquely his own in those years.

By 1939 everything had changed and he had a good, almost great band to go with his by now incredible technical ability. And the band jumped in more ways than one when, at the beginning of 1939, 21-year-old Buddy Rich took over the drum seat. Buddy stayed for a year during which he shook up the band, adding cohesion and bite to the sections with his punctuations. In 1992 Artie recalled that “when he came into the band he used to throw everything he had into every chorus, playing like the Czechoslovakian army. I taught him that it was better to start quiet and then build up. Eventually I talked him into quitting when I told him that he was playing much more for himself than for the band.”

Shaw didn’t exploit his new-found clarinet technique in any way and only used high notes when the music called for them. The solo team hit its high point in 1940 with the studio version of Stardust becoming the most successful single achievement of Shaw’s career. Arranged by Lennie Hayton, the piece began with a solo from Billy Butterfield and followed by one from Artie. Trombonist Jack Jenney completed the trio to perfection and this was indisputably the most breathtaking classic that any of the Shaw bands ever recorded. He remained a determined iconoclast in the face of the fans who idolised him. “All jitterbugs are morons”, he was reputed to have said, but it seems likely that that was really a misquotation by the press (Artie probably believed it in private).

Shaw was a very intelligent man, but it was once again the press who decided to pin on him the label “intellectual”. His mind was never still and he followed up many interests away from music.

“Artie Shaw was the most evil man who ever lived”, claimed the emotional Gene Lees without ever giving a public explanation. It didn’t stop Lees creating a brilliant and succinct portrait of Artie, written in the early 90s. That piece concluded “Articulate, witty, bookish, Shaw has lived his later years in a solitary retirement in California, carefully guarding his musical legacy even as he claimed it was of little interest to him.”

The book to get if you can is Artie Shaw: Non-Stop Flight (East Note: Hull Studies In Jazz, 1998), a 182-page paperback by John White, then reader in American history at the University of Hull. Edited by the much-missed Richard Palmer, it is succinct, lively, thoroughly researched and informative. It was revised and replaced by Artie Shaw: His Life And Music (Continuum, 2004).