I have in my collection a 60-year-old dubbing that is very worn because I think it to be one of the most consummate jazz recordings ever made and have fed off it over those six decades.

It’s completely relaxed and the atmosphere is ethereal. Although the sound has all the hushed dignity of a cathedral setting, it’s just a string of solos with piano, bass and drum backing. But what piano! And that’s not fair, because the solos sit in a sparse but beauteous setting, sketched by the pianist, which dictates the whole mood of the piece. I think that, in his era, he was one of the most accomplished of all the arrangers.

I have always thought that the reason I was never able to get a new copy was because, since the piece is seven minutes long, it’s the one that was always left out when compilations were being made. Seven minutes long? John Hammond, in his admirable series for Vanguard, was taking advantage of the recently introduced LP form.

Frequently over the years I searched for a new copy of my track but never found one. Or so I thought.

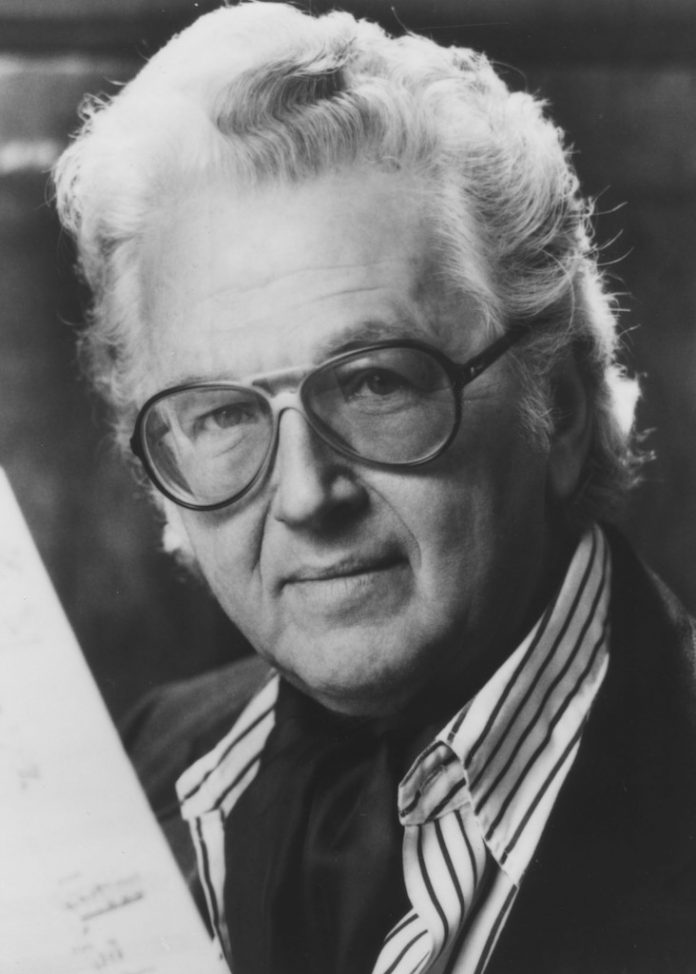

The pianist-arranger? He was a Pulitzer Prize winner who became a great music professor at Yale University and at other similar seats of learning. His given name was Melvin Epstein and he made some of his finest records when he was only 18. Incidentally, he won the Pulitzer for his concerto for two pianos and orchestra when his close friend André Previn put his name forward without Mel knowing.

Can anyone explain to me why, at least in the books on jazz pianists that I have available to me, Mel Powell is dismissed to the point of being completely overlooked?

Mel used his original name when he freelanced in New York during the late 1930s and changed it only when, aged 18, he joined Benny Goodman. Can anyone explain to me why, at least in the books on jazz pianists that I have available to me, Mel Powell is dismissed to the point of being completely overlooked? His albums don’t merit a mention in the Penguin Guide To Jazz Recordings.

Powell epitomised the “swing” of the swing era and was technically equipped as a pianist way beyond the needs of his jazz skills.

Mel rose swiftly when he freelanced in New York. He led his own band for the first time on record when he was 19. It had powerful and emotional trumpet from Billy Butterfield, shouting blues from Lou McGarity and some of the most convincing clarinet on record from one known as Shoeless John Jackson, the name Benny Goodman chose to hide his identity (some hope) from Columbia when he and Mel recorded for Commodore in February 1942.

The track on my 60-year-old dubbing, made for me by Ron Clough, for those of you who remember him, was I Must Have That Man, that haunting composition of Jimmy McHugh (lyrics by Dorothy Field) that Billie, Billie, Benny (as Shoeless John Jackson again), Lester Young and Buck Clayton casually turned into a classic on 25 January 1937 (nobody remembers the multitude of recordings that Duke made of the tune or the more than 20 by Red Nichols, Jimmy Noone and Venuti made before Billie got round to it. Mel had knocked it off at a Paris jam session with the Glenn Miller sidemen on 28 January 1945.

Mel’s second version of the tune, on my dubbing, was done on 30 December 1953 with Buck, Ed Hall, trombonist Henderson Chambers, Steve Jordan, Walter Page and Jimmy Crawford, originally on Vanguard VRS8004 (the other titles by the band were It’s Been So Long, You’re Lucky To Me and ’S Wonderful).

The track opens with the ethereal slow tempo that is to carry the piece throughout with Powell leading in Buck’s muted trumpet over Page’s sonorous bowed bass. Buck’s short statement gives way to Mel’s delicate embellishments on the melody, still with the arco bass. Buck comments again and then Mel ripples his way to a delicate but prosaic muted trombone solo. Buck returns to carry the melody into some Armstrong-like flights of improvisation, perfectly formed, before a most unusual solo from Ed Hall. We’re used to Ed being an attacking soloist, but here he’s almost Giuffre-like in his reticence. Many people wouldn’t have recognised him. Back to Mel for a more broad improvisation at his best, and then Buck returns for a magical restatement of the melody, ascending through a typically Louis-like climax to the coda. This was a fairly simple lead job for Buck and it’s one of the occasions when his perfect poise made the record. It certainly counts as one of his most sensitive appearances on record. One is left wanting more.

Happily I’d slipped into a blind-spot when I told you the track was unavailable for I subsequently found two pristine versions readily available – and they were in my own collection!

The whole session is included in Mel Powell – Six Classic Albums (Real Gone Jazz RGJCD420) at £8.49 or on Mel Powell – Four Classic Albums Plus (Avid Jazz AMSC 1063) at £3.99, both on Amazon.

Both albums include the magnificent Thigamagig and Borderline Vanguard sessions. The former features one of the best of Ruby Braff’s early performances – You’re My Thrill is from the same drawer as I Must Have That Man. Borderline swaps the tenor of Paul Quinichette for Ruby. The fine piano here is exemplified by the tough stride of Cross Your Heart, which is immediately contrasted with the more subdued but accomplished Lestorian tenor improvisations.

A pair of good anthologies made up from Mel’s Vanguard recordings appeared here on two of his albums – It’s Been So Long (Vanguard VCD 79605) and The Best Things In Life (Vanguard VCD79602). These are splendid, but likely to leave frustrated the listener who hasn’t got the complete original sessions.

“I began playing the piano when I was five”, said Mel, “and studied with the same lady for 10 years. I was astonished as a teenager to hear the playing of Teddy Wilson. He, Fats Waller, Earl Hines and Art Tatum, who became the despair of every jazz pianist, became my influences”.

In fact the lad’s jazz baptism was more specific. His younger brother Lloyd persuaded him, in 1937, to go to New York’s Paramount Theatre, where the Benny Goodman band was playing. He was astounded by the work of Goodman’s pianist, Teddy Wilson. By the time he was 14 he was good enough to get the job of intermission pianist at Nick’s, one of the city’s most historic jazz bars. One night a man who had spent the intermission listening carefully to the piano, leaned across and said to Mel “You’re going to be a real one”. It was Mel’s first encounter with Art Tatum.

Powell had already written arrangements for other bands when he joined the Goodman band in June 1941 at the same time as Sid Catlett, a man who Mel very much admired. Goodman, a deeply cynical man, probably couldn’t believe his luck. He had total respect for Mel and treated him as an equal – something that he didn’t do to any of his other musicians. The two had an almost father-son relationship, which lasted for the rest of Goodman’s life.

Powell started writing for Benny at once, soon producing two of his best, The Count and The Earl. They were followed in subsequent months by his arrangement of Jersey Bounce, which was to become one of Benny’s biggest hits. Usefully these can all be found on Hep CD 1055, one of a seminal series of CDs on Goodman’s arrangers. Called Benny Goodman Plays Mel Powell, it nevertheless has charts by Jimmy Mundy, Margie Gibson, Buster Harding and Art Lund, as well as the dozen by Mel. (It should be noted that the Hep series on Goodman’s arrangers is a definitive coverage of that part of Goodman’s history). Before his call-up Mel contributed two huge hits, Why Don’t You Do Right? and Mission To Moscow. The singer on the former was Peggy Lee, out of her depth on joining Goodman until Mel took her aside and ran through all the charts that her predecessor Helen Forrest had sung.

When Miller famously disappeared his deputy, Lieutenant Don Haynes, was given charge of the band. Haynes proved to be even nastier than Miller and the musicians took against him. Peanuts Hucko wrote a letter to his wife detailing what an unpleasant pillock the new boss was

Mel was drafted from Benny’s band into Glenn Miller’s AAF band in August 1942. Miller was known to be an unpleasant fellow, and a strict disciplinarian. But the musicians were each given the rank of sergeant and the money wasn’t bad.

When Miller famously disappeared his deputy, Lieutenant Don Haynes, was given charge of the band. Haynes proved to be even nastier than Miller and the musicians took against him. Peanuts Hucko wrote a letter to his wife detailing what an unpleasant pillock the new boss was. To avoid the army censor he gave the letter to a pal who was going home, but unfortunately the letter was intercepted when the man went through customs and it was returned, not to Hucko, but to Haynes. When he read it Mel and trumpeter Bernie Privin were implicated with their criticisms included in Peanuts’s diatribe. Haynes had all three demoted from sergeant to private, with the concomitant severe reduction in salary. Because they needed the money they began recording discs for commercial issue in Paris’s Jazz Club Français, where a disc-cutter was already wired into the sound system.

The discs are badly balanced and the sound quality is not ideal, but nevertheless they provide an attractive illustration of the musicianship of this tiny group. Peanuts is accomplished on tenor, Django (who was called to sit in for the first four tracks) a delicate delight and Mel fluent and eloquent, particularly on a version of his favourite Hallelujah. There’s an early I Must Have That Man, firmly despatched with ex-Tommy Dorsey guitarist Carmen Mastren, later to be famed for his work with Bechet-Spanier, replacing Django. Mel, as to be expected, solos beautifully. One can imagine him suggesting the tune for the session, and it’s one he must have worked over in many different forms – notably the ethereal Vanguard one that has attracted me so much. The 26 Paris recordings are crowded with imposing Powell solos, and indeed four of them, including a muscular stride tribute to Fats Waller, are unaccompanied. They’re on Glenn Miller’s GIs In Paris (Timeless CBC 1051).

“How I moved to what was described as ‘serious’ music – although of course jazz is serious music – was through boredom. I became bored with the repetitive routine in the Goodman orchestra and became more and more interested in composition. There was a reason for the simplicity and directness of my compositions for Benny and that was that I always knew exactly who was going to play what. There was no relationship between my arrangements for Benny and the so-called serious writing except for the covering of the pages in dots. There’s an enormous difference between the nature and complexity of the languages involved.

“Schubert once said ‘Composition is slowed-down improvisation’. That’s a very useful description. In my case improvisation is slowed down by two years”.

He returned to Goodman for almost another year appearing in the film A Song Is Born, a jazz venture terminally spoiled by the prominence of the appalling Danny Kaye

Powell steadily built his reputation in the States as a distinguished but minor composer, but in the period before that his jazz activities had continued after his military service was over. He rejoined Benny in August 1945 and this time stayed until June 1946, winning the piano category of the Downbeat poll in 1945. He became attracted to Los Angeles after visiting the city with Goodman and left the band to return there and work for a short time in the studios, writing for films alongside his new friends André Previn and Lenny Hayton. He also joined JATP for a tour and is on record playing accomplished and appropriate piano with a unit including Parker, Willie Smith and Gillespie. He returned to Goodman for almost another year appearing in the film A Song Is Born, a jazz venture terminally spoiled by the prominence of the appalling Danny Kaye.

Mel consolidated his “serious” work by studying composition with Paul Hindemith at Yale in 1952.

It was thought that his jazz life was ended, but he popped up yet again in the Goodman band between 1953 and 1955. He became a professor at Yale in 1957 and really did move out of jazz when he joined the California Institute Of The Arts, working there as a professor for the next 30 years. He returned to jazz, still a fluent and eloquent player as though he’d never been away, when he worked on a jazz cruise in 1986.

His life ended sadly. In the late 80s he developed a degenerative muscular disease and he died, from liver cancer, on 24 April 1998.

As so often, Whitney Balliett put his finger on the style. “His touch was oblique and dancing. Powell’s fast solos steamed. His single-note lines, decorated with little tremolos, flashed. His chords jumped three steps at a time. His accented notes, sounding every three or four measures, pressed the momentum. His slow solos were delicate and exploratory”.