This is the first full biography of Sonny Rollins to be published. It took seven years for Aidan Levy to complete. He interviewed Rollins many times during the process along with family members, neighbours, fellow musicians, associates and friends. The author searched countless newspaper and magazine articles for published reviews of Rollins’ many performances through the decades and examined every published copy of Downbeat to assess contemporary views and opinions of his recordings. Levy was also afforded full access to the extensive diaries and personal correspondence that Rollins has entrusted to New York’s Schomburg Centre for Research in Black Culture.

The legendary saxophonist himself is now 92. Levy begins his story in the Virgin Islands where Rollins’s great-grandparents were born and then methodically spans the years up to when the Covid-19 pandemic hit us in 2020.

Born in Harlem on 7 September 1930, Walter Theodore Rollins was nicknamed Sonny as he was the youngest in the family. His mother cleaned houses for a living and his father was a decorated US Navy steward in charge of 250 men. Rollins described him as stern. Levy recounts how it was his grandmother, Miriam, who exposed Rollins at a young age to radical left politics and to the black Pentecostal church where, deeply impressed by a trumpet player, he first learnt to swing. His older brother played the violin at home and his sister the piano. After seeing photos of Louis Jordan with a shiny alto saxophone and hearing jazz records belonging to his uncle, the young Rollins would plead repeatedly for a saxophone. Eventually, when he was eight years old, his mother conceded and bought him a used alto. He practised on it obsessively for several hours a day and in so doing set the pattern for a lifetime.

In his teens he traded his alto for a tenor sax in emulation of Coleman Hawkins. Now, bebop was the thing and Rollins formed a band, recruiting members from his neighbourhood including Arthur Taylor, Jackie McLean, Kenny Drew and Walter Bishop. His outfit, the Counts of Bop, played for two dollars a night at dances and parties. Levy tells us how Rollins went on to perform with more established artists such as Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, J. J. Johnson, Thelonious Monk and Charlie Parker and how at the age of 19 he came to record with one of his heroes, Bud Powell.

Rollins became a heroin addict early in his career. We hear how he joined the Clifford Brown/Max Roach group in 1955 and how the pair tried to keep him on the straight and narrow. Rollins finally came off the drug in the late 50s.

It’s not unusual for an extensive biography (772 pages in this instance plus 414 pages of notes) to contain passages requiring some revision or explanation. This is often due to the length of time covered and because the subject’s memory may have become clouded. I’ve spotted only two such occurrences here – one is the likely result of speculation on the author’s or subject’s part and the other is probably due to the subject’s misrecollection:

Levy describes an inauspicious night in 1956 when Clifford Brown, Richie Powell and his wife Nancy were driving in pouring rain from Philadelphia to a gig in Chicago. We read that “Brownie was tired and so was Richie. When Brownie thought he would pass out, he had Richie take the wheel. Then Richie did the same and changed seats with Nancy. Nancy drove on through low visibility while the men napped. Suddenly she lost control of the car.” It plummeted down an 18-foot embankment and all three were killed instantly. The account is puzzling for how would anyone know the circumstances of the journey if none of the occupants lived to tell the tale?

The other instance is Rollins’ account that when the Second World War came he “had to go down to Whitehall Street to be examined for the army”. He explained he was alienated and didn’t want to fight for the country. “We put pinpricks in our arms so we could say we were drug addicts and be exempted.” The problem here is that when the United States entered the war in 1941 Rollins would have been 11 years old. When he did reach the registration age of 18 no doubt he was minded to avoid the peacetime draft that was in place but this was well after the war had ended.

Throughout the book Levy narrates the circumstances surrounding Rollins’ many recordings including the critically acclaimed Saxophone Colossus, his extended protest piece Freedom Suite, A Night At The Village Vanguard and Way Out West. He also covers in depth Rollins’ extensive performance schedule at home and abroad including his many visits to Japan. A recurring theme is Rollins’ constant dissatisfaction with his delivery and his related obsession with finding “the lost chord” in marathon practice sessions. His search for perfection led him to regularly fire musicians in his bands. It became so frequent that Albert “Tootie’ Heath aptly declared that Rollins “would change musicians like he changed clothes”.

Turbulent episodes in Rollins’ life are covered by Levy. These include the circumstances surrounding his arrest for armed robbery and subsequent jailing on Rikers Island; his further arrest for parole violation with another custodial sentence, despite having voluntarily submitted himself for a “cure” for heroin addiction; and his later voluntary admission to Lexington rehabilitation centre where he stayed four and a half months to free himself from heroin after years hooked on the drug.

Rollins’ break from the music scene from 1959 to 1960 to concentrate on his health and spiritual development is recorded in colourful detail. We learn how he embraced yoga and weight training; of his burgeoning interest in religious and philosophical studies and his espousal of Rosicrucianism. Fresh light is shone onto his lengthy sabbatical on the Williamsburg Bridge where he played the sax for up to 16 hours a day, often till three in the morning. We’re informed by Levy that each day he’d go back home “to use the bathroom and get a cognac” before returning for more practice. Rollins maintains that he didn’t go on the bridge for publicity and it wasn’t some sort of weird behaviour. The simple and mundane reason was that it was the only space near to his New York apartment where he wouldn’t disturb the neighbours when practising at night. We learn that the reason he eventually came off the bridge was due to problems with his teeth and jaw when playing. He needed to earn some money again to pay for the high cost of the dental treatment that he required.

Rollins’ later pilgrimage to an ashram in India in search of spiritual enlightenment is covered later in the book. Other events featured in detail include life with his long-time wife Lucille; why he turned down a fortune that was offered to perform with the Rolling Stones; another two-year sabbatical when he became a recluse in Brooklyn and how he survived Ground Zero living just six blocks from the World Trade Centre (“He grabbed a flashlight and his tenor” before leaving.)

I have no doubt that this eminently readable and well-researched book on Sonny Rollins will be the standard biography for years to come.

The notes and references are available by download only from a link printed within the book. It appears that some web browsers may have difficulty in activating this link and if that should be the case the link at the bottom of Hachette’s page on the book can be used.

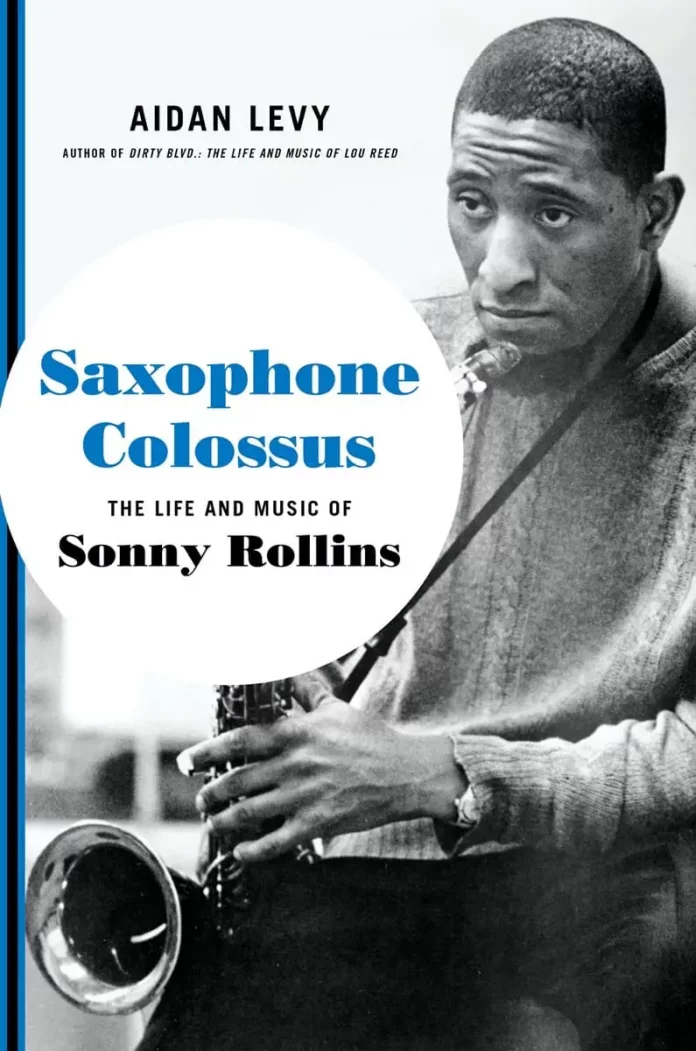

Saxophone Colossus: The Life And Music Of Sonny Rollins by Aidan Levy. Hachette Books, 772 pp, hb, £25. ISBN 9780306902796