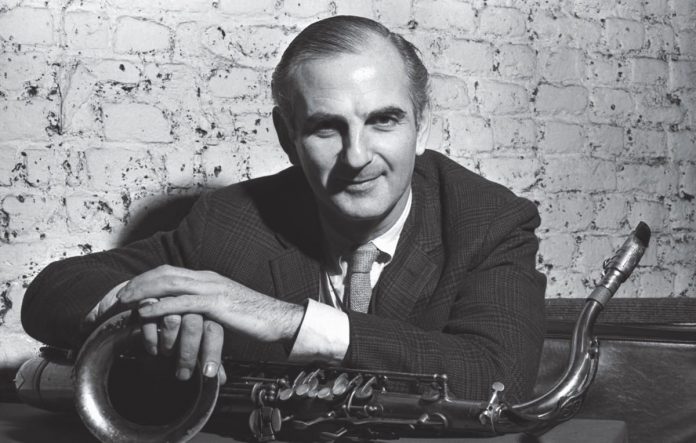

As Ronnie Scott himself said, “only an idiot would open a jazz club in 1959″. But he did, along with his close friend and business partner Pete King and that club is still thriving as a venue for the best in jazz over 60 years later. This film, released in Everyman Cinemas from 23 October, traces the life of Ronnie as musician and club proprietor from the earliest days in a small, dank basement in Gerrard Street, Soho to the present day premises in Frith Street, refurbished and brightened up by the new owners.

Back in the day, in that little basement club that had been a cab driver’s rest room, nobody expected it to survive a year, least of all Ronnie himself and Pete. When told that he would have been more successful if he had been a better businessman, Pete replied that if he’d been a better businessman he would never have started a jazz club in the first place. But the club’s success and enduring fame was always down to the two of them, working in tandem. Pete King did have some business acumen, otherwise it is doubtful it would have survived. The film traces the close relationship between these two incredibly good friends, their ups and downs, struggle to survive and the many times they owed vast amounts of money and it seemed that they could not continue.

It was, of course all about the music, as Ronnie repeats several times during the many interviews with him captured here. In the beginning he just wanted somewhere where he and his musician friends could play and not be at the mercy of other club owners. It all took off in a big way when they started to bring in top American jazz soloists, beginning with Zoot Sims. Once installed in the new premises in Frith Street they were able to present a weekly roll call of all the top names in jazz – and what a list of names it was. As Ronnie remarks in one interview it would be easier to list who did not play there rather than who did. Duke Ellington and John Coltrane were top of that list, along with Charlie Parker. Sonny Rollins made it, as well as Roland Kirk, Buddy Rich, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Elvin Jones and too many others to mention here. Ben Webster was a special favourite. Ronnie was amazed that such a player was “performing in my little club”.

The snatches of performances on view in this film only serve to make the viewer wish there were more of it to see. There’s Ella Fitzgerald singing about her man, Fine And Mellow, and conducting a conversation with her bass player’s strings, the audience in raptures; Roland Kirk playing three saxophones simultaneously and breaking off to play a flute solo, the saxes hanging on his chest; Cleo Laine in full vocal flight with the Dankworth orchestra; Sarah Vaughan sublime in a ballad; Van Morrison singing Send In The Clowns with Chet Baker playing soft focus trumpet filigrees behind him. During this one the camera lingers for a minute on a young lady in the audience. She does not speak but her expression says it all. He knows how to sing this in jazz mode and Chet knows just how to back him, she appears to be saying. Then there’s Sonny Rollins breathing fresh life into A House Is Not A Home. This and many more examples form the magic of Ronnie Scott’s.

The two faces of Scott are visible throughout. The man that could have the audience in stitches telling of Pee Wee Russell sending one cufflink every Christmas to his friend, the one-armed trumpet player Wingy Manone, also suffered from deep, debilitating depression. Stella King, Pete’s wife, tells of Ronnie coming to stay with them at Christmas and how difficult it was. “We dared not leave him in the house alone”, she reports, “fearing he might be dead when we returned.” At the end, when he could no longer play the saxophone, Ronnie told his partner “Mary, please understand. If I can’t play, I don’t belong here anymore.” At the inquest on his death the coroner returned a verdict of “an incautious dose of sedatives”, thus leaving open whether it was accidental or deliberate. Mary, once dubbed “Mary, Queen of Scott’s” by Ronnie and his daughter Rebecca, talk about his terrible bouts of depression but state that a good gig could always lift him out of his gloom. The gigs and the musicians around him that he admired lifted him time and again. His legacy was some great music and a wonderful club to hear it in. Jazz enthusiasts everywhere should see this film if they are near an Everyman cinema or, if not, hope it will appear on television before too long.

Ronnie’s: the life of Ronnie Scott and his world famous jazz club. A film by Oliver Murray. Abacus Media Rights, Orofena Films. Everyman Cinema Release