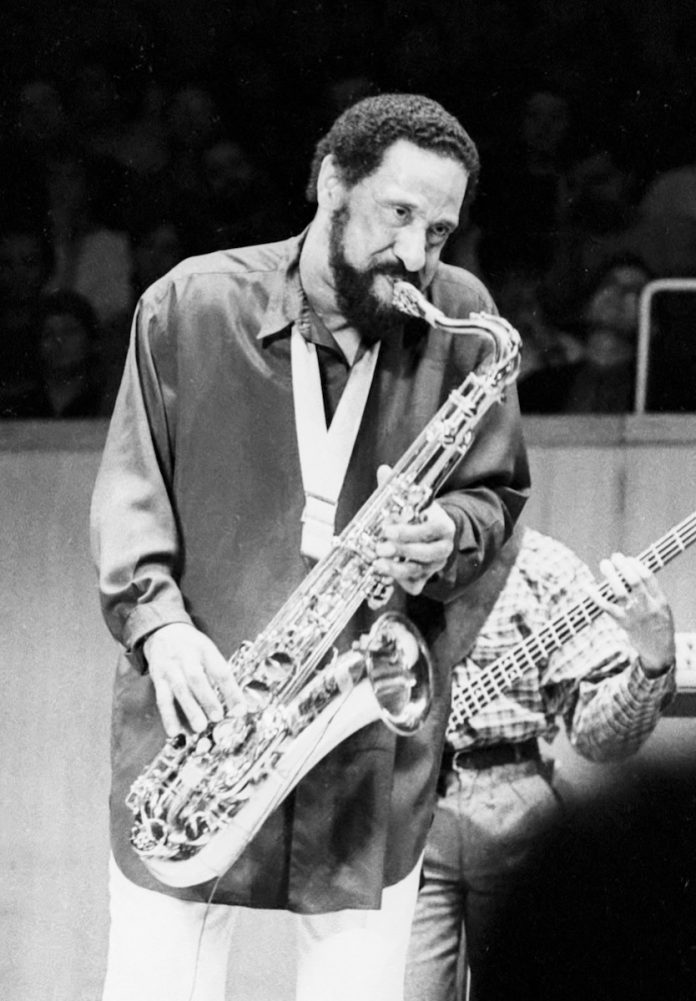

“What is he doing? One of the most influential of all tenor saxophonists playing Isn’t She Lovely or something called Disco Monk. It’s just not the Sonny Rollins of old!”

The quote is a fiction, but I’ve overheard not dissimilar comments on leaving recent concert or club performances.

At a point in his illustrious career when he could easily play safe, Rollins is still willing to explore, to acknowledge that the music around him has changed radically since the halcyon days of St Thomas, Sonnymoon For Two, Oleo and Airegin, performances contained on a string of albums that by the late fifties had elevated the saxophonist to a position of considerable eminence. Throughout the sixties and seventies, Rollins continued to investigate different forms in order to determine what further expansion and growth was available to him. He’s apparently always felt strong enough to take chances.

‘I know a lot of my fans would prefer for me to play the way I did in the fifties or sixties. I can understand that. I’m used to people hearing me in person and asking why don’t I play the way I did on such and such an album’

“If you listen to a performance of mine, I’m going to run the gamut from older things, old standards to more contemporary material. I’m playing things that I like and there’s a lot in the contemporary music scene that I enjoy and want to incorporate into my own expression. I would hope that it’s part of my particular musical gift that I can transcend specific styles and be valid regardless of the times and that I don’t have to be pinpointed as being from only one era of music. I know a lot of my fans would prefer for me to play the way I did in the fifties or sixties. I can understand that. I’m used to people hearing me in person and asking why don’t I play the way I did on such and such an album. All I can say is that I get a lot of inspiration from playing the spectrum of different types of music. I hope I’m always able to make room in my playing for things that are happening that I consider to be valid and that I can relate to.”

Stepping back in time, Rollins reflected on his early days. “I got a lot of help from certain musicians and when I was beginning, guys like Denzil Best, and later on Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Kenny Clarke and Oscar Pettiford were among those who encouraged me to keep playing at a time when I wasn’t sure that I really had the ability to be into it that much. Those guys seemed to think I should be more serious about developing and getting into the music.

“I don’t get a chance to listen to a lot of records today – I’m usually working or writing and trying to prepare for my next engagements and recordings but whenever there is time to hear some of the records that inspired me to play originally, the inspiration is still there.”

Rollins, more than most, is concerned with his public and their expectations. Those who have criticised him for not giving them what they feel he should might be a bit surprised by this concern. “I’m very well aware of the things that I want to improve in myself, both in the early days and today. On the occasions when I took the sabbaticals (twice in his career Rollins has stopped performing in public and on record), I was reaching a lot of people. I was playing before a much wider audience and I realised the tremendous responsibility I had to that audience and I felt I wasn’t always able to live up to it, so I figured that if I could take some time off and try to perfect myself, I would be able to get across to the audience better. I’m always trying to develop as I don’t feel that I’ve got the whole egg. I want to keep trying new things. That’s really a major part of what I’m about.”

Rollins’ concern with developing and perfecting his playing is further revealed in his attitude toward recording. “I don’t really enjoy it a great deal. I did more so in the earlier part of my career. I find that the confines of the studio inhibit me so I prefer to do concert or club recordings. In the studio I’ll re-do things – trying for a better take and that can go on for a long time. It’s a problem because I’m still a jazz musician in the sense that I’m looking for things to happen spontaneously and in a live setting where you can’t re-do anything, there’s more chance of that happening. The studio is something I have to deal with though, because you just can’t do live dates all the time. I like some parts of my recent albums. Some of the things on the ‘Milestone All-Stars’ record I was pleased with, but, of course, that was a live date. The ‘Easy Living’ album came out real well, but even on that record there were a couple of things where I felt another take could have gotten it a little closer to what I wanted it to be.”

‘I’ve heard records by John Coltrane that I know he wouldn’t have wanted released … It’s a reprehensible practice and the most blatant form of master/slave relationship where they feel they can take a musician and do whatever they want with him – he belongs to them’

Another aspect of recording bothers Rollins. Often, when a musician has moved to another record company, his old one will release material that at the time of recording was rejected for one reason or another. There is also the releasing of bootleg albums made up of material recorded surreptitiously in concerts or clubs. The musician in question is, of course, neither consulted nor paid. Both practices occur even more frequently with a musician who has died. “I’ve heard records by John Coltrane, for example, that I know he wouldn’t have wanted released. Now, for some historical reason, you might say that it’s interesting to hear how he sounded on the first take before he got it together, but it’s not what he wanted to do and as far as he knew it would never be out. I think it’s an invasion to do this to musicians and there are laws against it, but most musicians don’t take advantage of those laws. They do it to Bird all the time. They have a lot of his stuff which they put out and, knowing Bird, I’m sure he wouldn’t have liked any of it to have been available. It’s a reprehensible practice and the most blatant form of master/slave relationship where they feel they can take a musician and do whatever they want with him – he belongs to them. It’s a terrible situation.”

From recording, Rollins moved on to describe his reaction to record reviewers and critics in general. “I realise that they have their work to do, but I have found that some critics have certain preconceived points of view that tend to colour what they write – a particular axe to grind. At one time I was very upset by a lot of interviews and record reviews and I felt antagonistic toward some writers. It was at a period when the economics of the business were such that a good review in a magazine meant a great deal towards working. Things have changed in that it is not quite so important that you always get a good review for a concert or a record for the people to still like you.”

In closing, Rollins moved to a happier subject – describing a venture that is consistent with his desire to break new ground. “There’s some talk of a film that I’m supposed to be in. It would be about the New York music scene and things that are happening currently there as well as a sort of retrospective of some of the musicians that were around earlier. It’s something that would be a little different and exciting for me. Apart from that, playing is still a big experience for me – rehearsing, getting the music exactly right. These things are the constant battles and I’m just as interested in all of it now as I was when I started.”

Whether reshaping the contours of an old standard or a Stevie Wonder song, Sonny Rollins in 1980 continues to prove that he is one of the very few saxophone masters. Perhaps there are some listeners who are more concerned with what he is playing rather than how. If so, maybe they are missing the point.