Focused on the funeral parades of New Orleans, this documentary film recounts their evolution from 19th century parading clubs, benevolent associations and burial societies through to their present day status as one of the city’s well-known and most striking traditions.

The film is produced and directed by Jason Berry, author of the 2018 book, City Of A Million Dreams: A History Of New Orleans At Year 300, in which he traces the remarkable story of a city that has withstood all manner of disasters since its founding in 1718. Somehow, New Orleanians have always displayed remarkable strength, enduring two great fires, in 1788 and 1794, incursion in 1809 of thousands displaced by revolution in Haiti, a yellow fever epidemic in 1853, and in 2005 the impact of Hurricane Katrina.

Despite all these and more, what comes first to mind when New Orleans is mentioned is music. Since the late 18th century and throughout the 19th, music came to the city from many sources. From Europe, particularly France and Italy, came opera and brass band music; ceremonial dance music came from Africa via slaves freed after the civil war; also with them came early blues and gospel, zydeco – rooted in Louisiana’s French Creole heritage – and manifold genres that came to the city by way of Caribbean islands. Interwoven with all of this is the city’s status as the prime location for the evolution of jazz.

These outwardly diverse elements – death, destruction, music – come together at funerals and it is these that the film explores with music and dance the principal elements. Among the narrators through whose eyes the funeral tradition is traced are Mark Hertsgaard, Fred Johnson, Sybil Klein, Bruce Raeburn and, mostly, clarinettist and historian Dr Michael White, trumpet player and leader of the Young Tuxedo Brass Band Gregg Stafford, and writer and video blogger Deborah “Big Red” Cotton.

Although the city’s funeral tradition is the film’s core, the overriding sense is not of sadness but of happiness. This is expressed by the belief that the soul of the departed has gone to a better place and should be remembered for the life lived. New Orleans funerals therefore are not mournful occasions but celebrations. This is depicted through dancing in the streets, at a recreation of Congo Square and in particular during the funeral parades, among which are those for pianist-songwriter Allen Toussaint, drummer Louis Barbarin and civil-rights lawyer Lolis Edward Elie.

The marching brass bands that feature here play dirge-like hymns on the way to the cemetery and, on their return, the “second line”, their rousing music coming close to early forms of jazz. Familiar pieces heard amidst the non-stop music include Just A Closer Walk With Thee, performed by Michael White and Gregg Stafford at Louis Barbarin’s funeral; We Shall Overcome (this performed by White, Stafford and the Young Tuxedo Brass Band at the funeral of Lolis Edward Elie); Bourbon Street Parade (Ernest “Doc” Paulin’s Marching Band); Just A Little While To Stay Here (Stafford and the Treme Brass Band); Didn’t He Ramble (Dejan’s Olympia Brass Band); Flee As A Bird To The Mountain (White, Stafford and others); Clarinet Marmalade (the Louisiana Repertory Jazz Ensemble); Amazing Grace (the Treme Brass Band and the Black Men of Labor). Less familiar are Kibunu and Mabele, performed by Titos Sompa and Congo Square Dancers and Musicians, and A Ja Ja, by Kumbuka African Dance & Drum Collective.

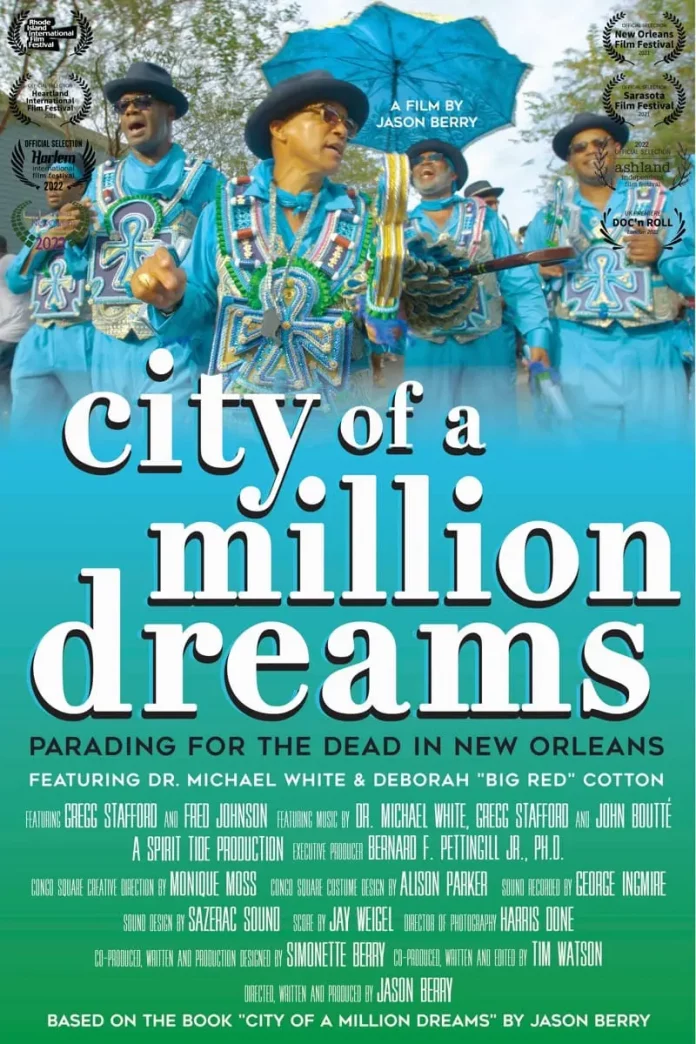

All of this vibrant music is enhanced by visually striking images as cameras follow and mingle with musicians and dancers. Early in the film, Deborah Cotton observes “This city wears two faces, just like the Mardi Gras masks, tragedy and comedy.” There, she is referring to the Mardi Gras marches of the Masked Indians, whose members are garbed in elaborations of Native American costume. And the immaculately attired marching bands also draw the eye. Interspersed with contemporary filming are clips from past decades, including the funerals of Paul Barbarin and Danny Barker, and from these can be seen how style of dress has been retained and with it a sense of the past.

As for the present, threats to ordinary life in New Orleans are mirrored by the experience of one of the principal narrators, Michael White, a descendant of Papa John Joseph, who speaks of how his home and all that was in it was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina. This loss of decades of research material proved to be life changing, nevertheless, both White and his surroundings, shattered though they were, are overlaid with the prevailing optimism that is exemplified by the funeral tradition in New Orleans.

The mood is darkened dramatically however when another of the film’s narrators, Deborah Cotton, then in her late 40s, is seen filming a parade on Frenchmen Street on Mother’s Day, 2013. A shooting incident takes place and she and Mark Hertsgaard are among almost 20 people injured. Sustaining a severe abdominal wound, Deborah Cotton had to undergo major surgery for damage to and loss of internal organs yet managed somehow to return to work on this film. The cumulative effect of the wound and subsequent treatment (more than 30 surgical interventions) was such that she died in 2017. That her own funeral, at which Michaela Harrison sings Ise Olua, a traditional Yoruba air, should become a part of the film to which she contributed so much is sadly ironic. This unexpected and tragic death serves to heighten awareness of the sometimes brutal yet everyday reality of life in major cities. That reality is masked by the outward optimism displayed by the funeral parades of New Orleans, which, to paraphrase Michael White, can be seen as a means of transition to a new, spiritual existence.

Although this film is a companion piece to Jason Berry’s book, neither is dependent upon the other. Throughout, the film vividly captures a tradition that remembers and honours those who have left an indelible mark not only upon the city, but also on the culture and music of the wider world beyond.

City Of A Million Dreams: Parading For The Dead In New Orleans, a film by Jason Berry (producer and director); Harris Done (cinemaphotographer); Jason Berry, Simonette Berry, Tim Watson (co-writers); Michael White, Gregg Stafford; Deborah Cotton (narrators). 89 minutes.