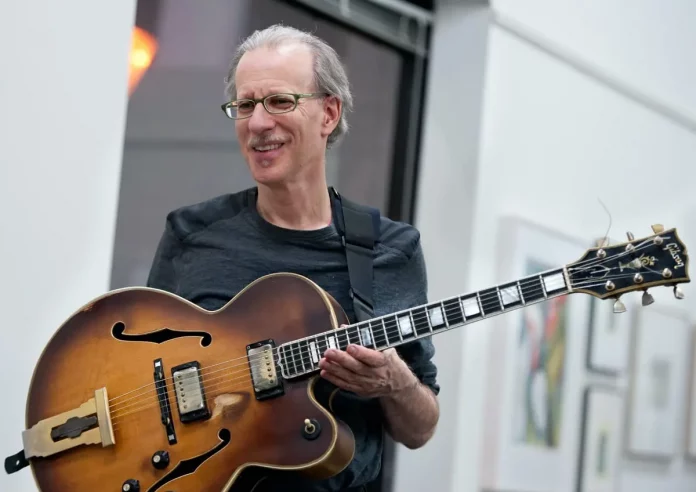

While many jazz guitarists of Joshua Breakstone’s generation – Pat Metheny, John Scofield, Lee Ritenour, Mike Stern, etc. – built successful careers playing jazz-rock or fusion, he has forged a more traditional path. Stylistically, a straight line links him to Charlie Christian as it bisects the work of men like Barney Kessel, Herb Ellis, Jimmy Raney, Tal Farlow, Johnny Smith, Kenny Burrell, Wes Montgomery and Grant Green, Christian’s most celebrated disciples and Breakstone’s natural forebears.

Like these past masters, Breakstone combines elements of bop and swing into a modern-mainstream style built on balance and logical construction of ideas. Joshua’s solos – as with all master improvisers – are like musical stories or journeys that reveal the melodic and harmonic dimensions of the tunes he loves to play. His deft, soft touch creates a sound that burns with the intensity of a low but lively flame. Technically assured at any tempo from ballad to breakneck, he maintains a velvety core, even when swinging hard.

‘The way both Lee Morgan and Clifford Brown articulate each note has been a great influence on the type of sound I try to get on guitar’

His cleanly picked lines are intricate but uncluttered, leaving plenty of space for the music to breathe, the notes to ring, the emotions to process his sculpted yet organic and spontaneous musical excursions. They are quirky, too, leavening the music with humour and a sense of surprise as the listener contemplates how a twisting strain will resolve itself. Yes, it is intellectual, but it appeals to the emotions as well, leaving a warm glow that lingers as the music fades.

I first interviewed the guitarist in Osaka in 2005, during one of his frequent Japan tours. (Since 2018 he and his wife Nathalie have resided in Kyoto.) However, I shelved the interview when the magazine I had intended it for appeared to lose interest. A few years later, Joshua and I and another friend spent a day exploring the hills and temples on the outskirts of Kyoto City. We ended that charmed day bathing at a Japanese onsen, where, warmed by the hot spring and the beer we had consumed, Joshua related delightful vignettes of encounters with the likes of Art Farmer, Warne Marsh, Sonny Stitt and others. These experiences convinced me Joshua’s story deserved to be told, leading to a phone chat at the end of September 2022. The result follows.

Joshua Breakstone was born 22 July 1955 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, just across the Hudson River from NYC. He began guitar around age 15 and was soon playing rock and roll with friends. His introduction to jazz came from a friend of one of his older sisters, saxophonist Rick Centalonza, at that time with the Buddy Rich band. Still in his teens, Joshua used to travel with Centalonza. “They’d have these one-nighters up in New York State, and I would go. We’d ride to those gigs, and the whole way, we would listen to music. That’s when I got turned on to a lot of people – a lot of Charlie Parker.” The reference to Bird is telling in that Breakstone recalls listening more to horn players than to guitarists in those years, Lee Morgan and Clifford Brown being favourites.

Liking what he heard, Joshua began the transition from rock to jazz. As he explained to Bill Milkowski for the liners of one of his records: “The way both he [Morgan] and Clifford Brown articulate each note has been a great influence on the type of sound I try to get on guitar.” He was also attracted to Morgan’s fiery attack.

He spent the early to mid-70s studying at the New College in Sarasota, Florida and did a couple of terms at Berklee College of Music in Boston. While these experiences proved of some worth, studying with legendary Kenton guitarist Sal Salvador had a much greater impact. Centalonza was again the catalyst, facilitating Joshua’s introduction to Salvador. “That was really good,” recalls Breakstone. “He gave me a really wide array of materials to work on. Every week I was working out of about 12 or 13 books.”

He had begun playing jazz gigs during his time in Florida, and after his return to New York, worked club dates and toured Canada with saxophonist Glen Hall, who also used him for a record date in 1976, Josh’s first. Through the late 70s to early 80s he gigged with other promising young players such as David Schnitter, Emily Remler and Vic Juris, as well as veterans like Barry Harris and Vinnie Burke, the bassist.

As notice of his abilities grew, he attracted attention for having something fresh to say within a grand tradition. Early one morning, he was awakened by a call from Warne Marsh. Though the two had never met, Warne wanted to know if they could get together and jam that morning. Joshua asked if later would be okay, and so the two met that evening at Warne’s place. In February of 1982, Joshua arranged a club date in New Jersey for himself and Marsh. The following May, Marsh asked the young guitarist to join him for a gig at Eddie Condon’s, Joshua’s debut on the storied 52nd Street.

Years later, Joshua wrote about the experience in a piece included in my book Talking Jazz: Profiles, Interviews And Musings From Tacoma To Kansai. The following excerpt tells how the Condon’s gig opened Breakstone’s eyes to the economic realities of life as a professional jazz artist: “Warne and I went out onto 52nd Street on a break that night. I was being paid $90 and was delighted to make money like that at a time when most jazz gigs were paying $50 or less. He asked me ‘Do you know what I’m making on this gig tonight?’ He told me it was $100, [and] added that he’d played many times at the same club on weeklong engagements in the 1950s and had made the same amount. He went on to tell me that in the 1950s, with $600 in his pocket from a week at Eddie Condon’s, he could pay his rent for the month, make his car payment, go out and buy some new suits, and still have money left over. In 1982, $100 didn’t go too far. A long time had gone by but musicians were still being paid the same as they had been 30 years before. I don’t think the situation has changed much since.”

By 1983, he was ready for his first record date as leader on the independent Sonora label. The debut recording, called Wonderful!, featured what Breakstone refers to as “one of the great pairings of jazz,” Barry Harris and Leroy Williams, plus Earl Sauls on bass. “I lived right around the corner from Barry, and of course, I had loved his playing forever,” says Breakstone, adding, “I asked Barry, and Barry said ‘Yes.’ I was very complimented by that.” For his follow-up Sonora release, he again demonstrated impeccable taste in his choice of sidemen, tapping the talents of Kenny Barron for another quartet session. Due to a studio glitch, the album was waxed in record time: “I think we had an hour and 15 minutes, and that’s what we did that record in!”

Not long after this date, he recorded an album with baritone sax great Pepper Adams that he hoped to have released on Herb Wong’s Blackhawk label. But Breakstone – having flown to San Francisco to discuss a contract – informed Wong not to bother when he failed to make himself available for a scheduled meeting. Joshua next called Bob Porter who suggested he contact Ralph Kaffel, president of Fantasy Records. To make a rather long story short, Joshua played the record for Kaffel who loved it. Kaffel agreed to release it on Contemporary providing his partners in Japan would do the same on their Victor JVC label. Japan agreed, and Joshua signed his first major label contract Echoes, featuring Adams and Kenny Barron, was released by Contemporary in 1986, followed by three more for the label with such established players as Jimmy Knepper, Tommy Flanagan and Kenny Washington.

The Victor JVC connection opened the door to the scene in Japan when Josh was brought over to do some promotion for the Echoes album. A chance meeting with the late bassist Mitsuru Nishiyama changed Joshua’s life. “I was in Osaka and somebody took me to a club called the Sub Club . . . and I played with Nishiyama [the club’s owner] no longer than 10 minutes, and we knew were like brothers . . . so we played and 15 minutes later, he asked me if I would do a tour in Japan. Six months later I was in Japan for my first tour, and he brought me every six months.”

A few years later, Yoichi Nakao – head of King Records in Japan – came to see Joshua in a Tokyo nightclub when he was on tour. Upon Nakao’s invitation, the two later met at his office. When Joshua casually mentioned his contract with Contemporary was ending that year, Nakao acted decisively: “He grabbed me by the arm, got a guy from the legal department, and the day after my contract with Contemporary ended, my contract with King Records for four records started.” One result of the King connection was a fine tribute to Grant Green with Brother Jack McDuff and drummer Al Harewood. McDuff and Harewood had previously constituted the rhythm section for Green’s 1961 Blue Note classic, Grantstand. (Subsequent releases on various labels have paid tribute to Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Wes Montgomery and, most recently, Art Blakey.)

Since 2001 Breakstone has released no fewer than eight albums on his current label, Capri. His choice of side players maintains the high standard he set for himself with his very first record. They include such stellar talents as Lisle Atkinson, Eliot Zigmund and Louis Petrucciani, to name a few. Capri has allowed him the freedom to explore non-standard modes of expression such as his cello quartet with bassist Mike Richmond on cello. The inspiration for this group came when Mitsuru Nishiyama – Joshua’s soul brother – played cello on one of the guitarist’s tours. As Breakstone explains in the notes to the first Capri CD featuring the quartet, With The Wind And The Rain: “I enjoyed the sound of the cello from the start. But it wasn’t until I started hearing the quartet . . . as, essentially, a string section . . . that the beauty as well as the possibilities of this formulation really struck me.” Two more records featuring the quartet – 2nd Avenue and 88 – appeared in 2014 and 2016 respectively.

As Mr. Marsh had warned all those years before, one doesn’t get into jazz for the money. When I asked Joshua how it has been financially, he answered without hesitation: “Terrible!” This is even more so now than ever with easy access to digital music sources. But with some two dozen leader albums under his belt and nearly 50 years of performing with some of the greatest names in modern jazz, Breakstone can be proud that he has never compromised his mission to create works of beauty and meaning within the parameters set by those who preceded him. Save for guitar amplification, he avoids electronics, pyrotechnical displays and effects, creating an impact through excellent playing, inspired arrangements and the relaxed drive a good jazz musician can generate.

Guided by a genuine artistic sensibility, Joshua Breakstone is playing at the top of his game and shows no sign of slowing down. And as disruption from the pandemic continues to abate, the music business in Japan is springing back to life. From his home base in Kyoto, Breakstone is again touring, playing local gigs and pursuing related activities. The dedication and gifts of artists like this fine guitarist ensure that jazz music burnished by the best qualities of its collective history will find favour for the immediate future and likely a long while to come.