John White’s instructive tour through Philip Larkin’s writing on Louis Armstrong got me thinking. I can well understand Larkin’s ire when, in James Lincoln Collier’s biography of Armstrong, he read the words “I cannot think of another American artist who so failed his own talent”. They were harsh and uncalled-for, but a similar view, implied if not so directly expressed, was common among jazz devotees for many years.

‘This eventually solidified into the doctrine of “jazz good – entertainment bad” which has dogged jazz ever since’

It originated in well-meant attempts by early jazz commentators to separate “true” jazz from the knockabout trivialities of popular music in general. This eventually solidified into the doctrine of “jazz good – entertainment bad” which has dogged jazz ever since.

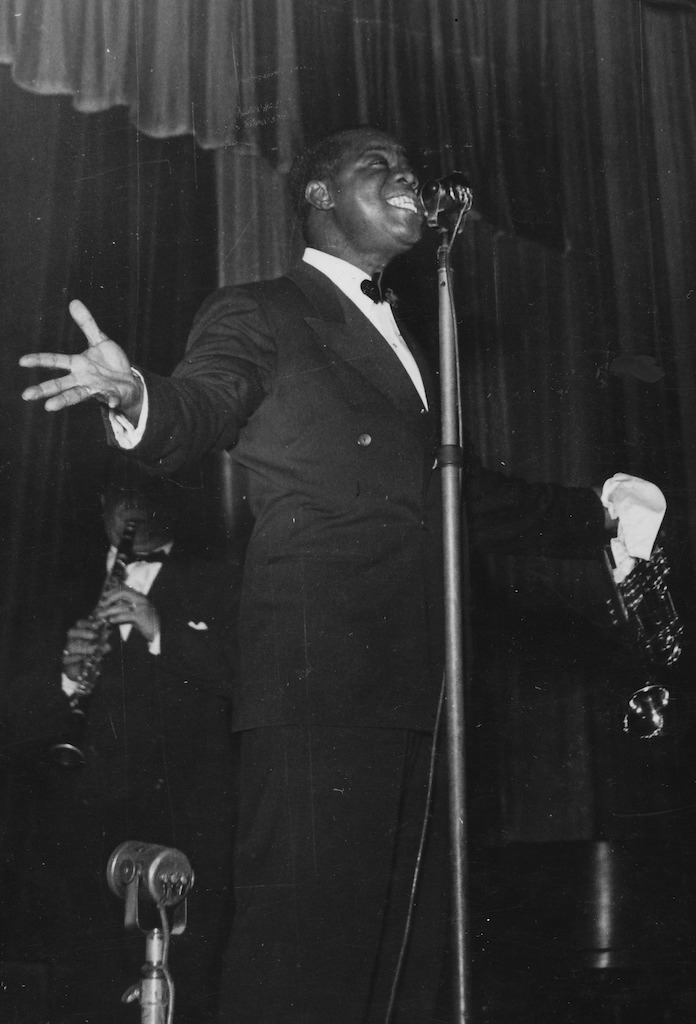

It was difficult, if you’d been brought up under the influence of this idea, not to feel a bit bewildered by a typical All-Stars performance. I was among the thousands who attended one of Armstrong’s shows at London’s vast Empress Hall (now demolished) in 1956. Twice a day, for 10 days, he walked onto that stage to be greeted by a wave of unconditional love from thousands of people, most of them standing to applaud, some so overcome by his very presence that they were weeping.

In all my teenaged years I had never experienced anything like it. When the music got going, I wasn’t exactly disappointed, but sort of waiting for something. Then, during one of Velma Middleton’s songs, Louis began casually filling in between the vocal lines and there he was! Just for a moment, the creator of West End Blues and Hotter Than That was unmistakably before us.

That, at any rate, was what occurred to me. I don’t know if anyone else noticed anything. Since the stage was slowly revolving throughout the performance, it was sheer chance that Louis was facing my part of the hall at the time. It’s entirely possible, too, that I was so eager to catch a flash of genius that I made a mountain out of a mole-hill. It was obvious by the end of the show that it had been the magnetism of Louis himself, his playing, his singing, his drolleries, the whole thing, that had captivated the crowd. The same had attracted crowds to Chicago’s Vendome Theater in 1926 and it had sustained him ever since, especially throughout the life of the All-Stars, which began in 1947.

Collier’s view of this was that Armstrong had “never escaped the limitations of having been born into the depressed and deprived working class of the Deep South” and had consequently settled for “a career of stage mugging and eye-rolling vocals” – i.e. the aforementioned singing and drollery. Outraged by this, Larkin had eloquently taken Collier to task, as quoted by John White. We can be fairly sure that neither Louis nor any of his New Orleans contemporaries would have understood what Collier was complaining about. Louis believed that he had been put on this Earth to make people happy, and that everything seemed to be going according to plan.

Collier’s biography is not a bad book; it’s just that he doesn’t begin to grasp Armstrong’s value system, or, if he does, he dismisses it. First published in 1983, the book is also somewhat out-of-date now, since more information has come to light. Even the true date of Louis’s birth wasn’t known in 1983, although Collier made a diligent attempt at establishing it, coming up with the suggested year 1898. The correct date, 4 August 1901, was discovered in a church register in 2001. (It was a Roman Catholic church, and Louis had always maintained that, according to his mother, he had been baptised in a “white” church.)

Collier upset Larkin most seriously with his claim that Louis, because of his lowly birth and upbringing, had became “subservient to a succession of ruthless managers who treated him like a performing animal”. It may have looked like that to outsiders, particularly in the early days, but Louis Armstrong was nobody’s fool or underling. Once again, we now know a lot more about the way he organised business matters to his own satisfaction, notably the 35-year-long and strangely symbiotic relationship with his last manager, Joe Glaser. The details appeared in What A Wonderful World, a splendid book about Armstrong’s later years, by Ricky Riccardi, published in 2011.

‘Louis had the stronger hand of the two, because he could exercise the nuclear option. He only found it necessary to threaten it once’

Glaser was no angel. He was a hoodlum. He’d been one of Al Capone’s henchmen in the 1920s and had wide connections in the underworld. In 1935, Louis made him an offer he couldn’t refuse: “I want you to be my manager. You give me one thousand dollars a week, you take care of everything – bookings, band salaries, taxes, security, everything – and you keep the rest”. A thousand dollars a week in 1935 was a lot of money and Louis was quite happy with that. What he didn’t want was trouble. Music was his business, trouble was Glaser’s. They shook hands on the deal.

During the All-Stars years, Louis Armstrong became a million-dollar attraction. No doubt the original grand a week grew proportionately. He appeared in films and on television, his records sold well and, of course, there was the endless touring. Glaser represented many other artists, but Louis and the All-Stars provided the solid backbone of his business. They both knew it and each stuck faithfully to his side of the bargain. Louis had the stronger hand of the two, because he could exercise the nuclear option. He only found it necessary to threaten it once.

On New Year’s Day 1954 Louis, his wife Lucille, and the All-Stars flew from Tokyo to Honolulu. On their arrival, customs officers found a small amount of marijuana in Lucille’s handbag. She was arrested and released on bail. At the subsequent trial she was fined $200, reduced to $100 in recognition of the charity show the All-Stars had given on the previous day.

The story was all over the world’s press. Louis was furious. Nothing like this had ever happened during the All-Stars’ existence. The deal with Glaser was for “no trouble” and this was trouble. In a long letter, Louis pointed out that he had chosen Glaser, not the other way around, that he himself had smoked joints all over the world without any trouble, and now this had happened to his beloved Lucille. If such incidents were likely to be repeated, “I will just have to put this horn down, that’s all. It can be done. Nothing impossible, man”. Nothing of the sort ever happened again.

Retirement, the nuclear option, was an ever present possibility from that moment. When push came to shove, who was the performing animal then?