In the late 1940s the first wave of World War II novels began to appear. The positives were that the authors had actually served in the armed forces, allowed their experiences to germinate and then put pen to paper. The negatives were that as a rule no one man served in more than one theatre of war, thus restricting the scope of a global conflict – The Naked And The Dead (the war on land in the Pacific), The Caine Mutiny, Mr. Roberts (the war at sea in the Pacific), The Longest Day (D-Day), The Cruel Sea (the war in the North Atlantic).

In 1948 a more fully rounded picture emerged with the publication of The Young Lions. Rather than a serving participant author Irwin Shaw was a war reporter cum documentary film maker who covered the war extensively throughout Europe and North Africa as did his novel.

It was very much the same with Hollywood and jazz. Several fine films have been released but have dealt with one localised area – Clint Eastwood’s Bird covered the life and career of Charlie Parker, Bertrand Tavernier’s Round Midnight was a fictionalised account of a real life friendship between pianist Bud Powell and a French fan albeit pianist was now a saxophonist, played by Dexter Gordon. For earlier jazz the one they all had to beat was Jack Webb’s Pete Kelly’s Blues; and so on.

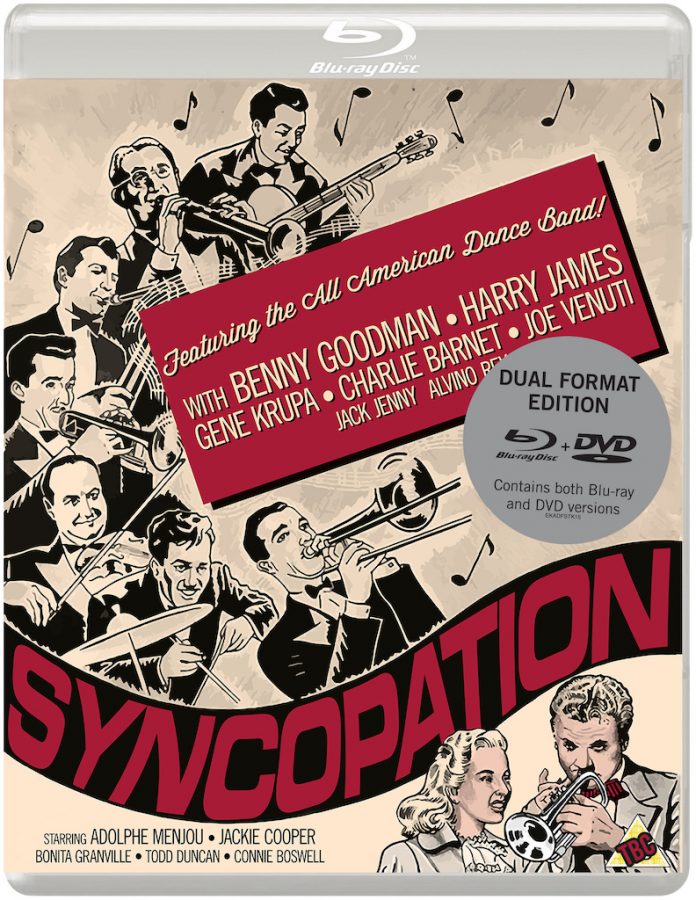

But in 1942 expatriate German director William Diertle attempted to cover the whole spectrum of jazz from its roots to the swing era. In what today was a blatant PR stunt RKO invited the public to vote for the real musicians they would like to see playing in the climactic jam session via a poll in The Saturday Evening Post and the winners were Charlie Barnet, Alvino Rey, Joe Venuti, Jack Jenny, Harry James, Gene Krupa, and Benny Goodman.

This starry septet was a long way from the opening sequence in the African jungle where natives are swaying to an infectious rhythm as a white trader barters with the chief. The natives are clapped in irons and transported to the New World represented by New Orleans circa 1900 where a young black boy, around 10 or so, is blowing the bejesus out of a cornet in a music school.

This is where the film scores big, because the boy is clearly meant to be Louis Armstrong, who learned to play in the orphanage in which he grew up. But this boy lives with a mother who is not best pleased when he is offered a job by King Jeffers. Again ambiguity rears its enigmatic head; we know that Armstrong played with Joe “King” Oliver early in his career, but there was also another cornet player known as “King” in the shape of Buddy Bolden.

This is, to some extent, academic as we are about to quit New Orleans for Chicago, having now met our leading lady Kit Latimer (Bonita Granville), a gifted “stride” piano player. Her father George (Adolphe Menjou), a talented architect, is persuaded there are more opportunities in the Windy City and so, neither happy to do so, father and daughter embark on a riverboat passing through Memphis and St Louis, both, of course, bustling with jazz.

In Chicago Kit meets Johnny Schumacher, who tells her he is a trumpet player playing weekends with a group of friends from high school, again clearly meant to be the Austin High school gang. Time and again the film does this – throwing in references that will please the real jazz buffs without impairing the storyline for ordinary viewers (Johnny, for example, is also a nod to Bix).

Moving through ragtime, blues and boogie woogie, we finally arrive at swing. Kit and Johnny get married and struggle. They quarrel too, when, in yet another glaring reference, Johnny goes on the road with Ted Browning, an orchestra leader who pioneers “symphonic” jazz – an obvious harpoon aimed at Paul Whiteman, self-styled “King of Jazz”, with whom Bix, of course, played for a time.

It all comes right in the end when the real Connee Boswell playing herself shows up to support Johnny’s band – but not before one character throws in one final reference to “a zoot suit with a reet pleat” and the seven real life musicians play us out with a jam session that has absolutely nothing to do with the rest of the film.

First released in 1942, this film somehow slipped under the radar but it’s here presented again for a new generation and old buffs in 1080p on Blu-ray from a 2K restoration completed by the Cohen Film Collection.

Syncopation, directed by William Label and featuring Charlie Barnet, Benny Goodman, Harry James, Jack Jenney, Gene Krupa, Alvino Rey, Joe Venuti and Connee Boswell. Eureka Classics, dual format (Blu-ray & DVD), EKA70375, b/w, 88 minutes, RRP £17.99