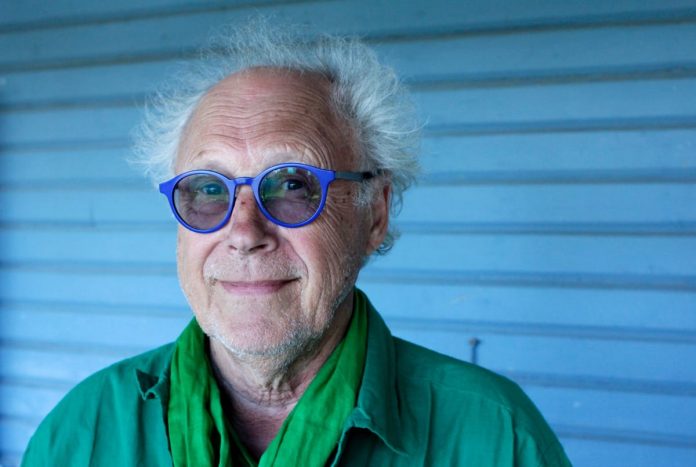

The Swedish drummer and percussionist Bengt “Beche” Berger has long been one of my favourite musicians. A kicking drummer as well as a painter and poet of many a modally sprung mood, Berger is both his own person and one of the most co-operatively inclined of musicians. Some of his most memorable projects, such as the 1981 Bitter Funeral Beer, have drawn upon musicians associated with the Stockholm-based musicians collective Ett Minne För Livet (A Lifetime Memory) while the Country & Eastern label which he set up in 2005 is dedicated to an unusually broad spectrum of music.

At root a touch more Ed Blackwell than Elvin Jones – if one had to offer an indicative characterisation – he’s always been open to pushing the musical, social and spiritual parameters of the music. At the same time, Berger – a Gretsch drums and Zildjian cymbals man – has remained keenly aware of core jazz values, with a penchant for complementing widely configured explorations with passages of freshly energised old-time swing, chasing choruses and both blues bite and harmonic colour. Hear, for example, tracks like Old & New Blues and Maximum from the 2015 Blue Blue which he cut with fellow Swedes Jonas Knutsson (s), Max Schultz (elg) and Christian Spering (b) – or the title track and Mingus from the live sextet and septet sessions which constitute the 2018 Gothenburg.

Happily, a practically cinematic sense of humour is no stranger to Berger’s muse. Far from it: witness pieces such as Gothenburg‘s Flabby Dick and Hanuman Jump or the in-part tongue-in-cheek hypnotic shamanising at the beginning of his recent Viltvarning (Wild Life Alert) release of a shape-shifting large-ensemble live concert from 2002 at Stockholm’s Fasching club. Speaking to me, Berger recalled a special evening which had offered to the patrons a “wild” menu of both food and music. “The concert had an Elk Guarantee – it started with the audience being hypnotised by me to see an elk passing through the room sometime during the evening, otherwise the money back. Since nobody wanted the entrance fee back, an elk must have passed through the club. A rare thing indeed.”

Over the years, I’ve been lucky enough to see the occasional elk. Sadly, I’ve never managed to catch Berger live. But his music has nourished me for what is now getting on for half a century – ever since I first heard him on the Rena Rama quartet’s recorded debut, the eponymous Jazz I Sverige 1973 session for Caprice Records. Together with fellow Swedes Lennart Åberg (ts, ss, f, pc), Bobo Stenson (p, elp, pc) and Palle Danielsson (b, pc) Berger here helped shape one of the most vibrant releases of its time.

With rhythms such as 2/4, 7/8 and 13/8 the music swung strongly, but in a new and distinctive manner, drawing both melodic and rhythmic inspiration from folk melodies such as Batiali, a Pakistani piece reconfigured by the group. YouTube has a compelling half-hour or so of a black-and-white Swedish TV broadcast of the quartet in its early days, where Berger’s cross-rhythmic mastery of the traditional drum kit is as notable as his contributions to those episodes where all members of the group help shape a percussive web of rhythmically intricate, Eastern-inflected colour and atmosphere.

As Erik Centerwall put it in his sleeve note for the 2003 CD reissue of that first Rena Rama release: “It was the 70s, and jazz was searching for contexts in which it could develop, both musically and economically.”

Born in Stockholm in 1942, Bengt Berger heard his first jazz concert in 1956: “That was a Jazz At The Philharmonic touring show which had Gene Krupa playing with Dizzy, Eldridge, Oscar Peterson and others. I always loved jazz and admired (still do!) the greats like Max, Kenny Clarke, Roy Haynes, Blakey, Philly Joe and all. I could get what they did but when I heard Elvin it was something else, not so easily analysed. I started to play really late, at 20, but practised like crazy with the idea that, OK, I’m allowed to play anyway I want and I know what I want!”

A member from 1969 to 1971 of the genre-crossing avant-rock / folk group Arbete och Fritid, Berger had already begun to develop what would prove to be a lifelong fascination with diverse “folk” and “ classical” traditions, with a special interest in Indian and West African music and culture. He lived in India for two years in the late 1960s. There he absorbed the talas and studied, with P S Devarajan, the mridangam (the two-headed drum which furnishes the primary rhythmic foundation of the Carnatic music of southern India) and, with Pandit Taranath, tabla (the twin set of drums central to the Hindustani music of northern India).

Later, Berger would be domiciled in Ghana for a comparable period, studying with the xylophone master Kakraba Lobi and with Ewe and Brong-Ahafo master drummers. When he returned to Sweden he and his long-time colleague, the multi-instrumentalist Christer Bothén, joined Archimedes Badkar, the Swedish “world music” group which had started in 1975. It was here that Berger first tried to incorporate the Ghanaian Ko-Gyil xylophone, which can be heard on the 1978 Bado Kidogo release.

Berger came of age as a musician at a time when Swedish jazz was undergoing substantial changes of identity and aspiration: changes to which he – together with such similarly open-minded players as Bernt Rosengren (born 1937) and Christer Bothén (born 1941) – would make vital contributions. The established, cool and swinging world of such leading and popular figures as Arne Domnerus and Putte Wickman, Jan Johansson and Lars Gullin would be challenged: initially by the drive and energy of hard bop and then by an emerging free-jazz scene.

Bernt Rosengren (saxophone, flute, tárogató) was a major figure in both these developments – and would do a great deal for the organisational side of Swedish jazz. While the 1965 award-winning Stockholm Dues showcased Rosengren’s long-established mastery of the hard bop idiom, his key 1973 double LP Notes From Underground – its title referencing Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s proto-existentialist classic as well as suggesting how difficult things had become for forward-looking musicians in search of places to play – exemplifies how the new music had absorbed various aspects of other genres.

Commencing with a theme from Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2, the album went on to manifest both a Coltrane-fired potency (hear the various Some Changes pieces which are distributed across the two LPs) and the sort of cross-cultural blend typical of the contemporary Turkish-Swedish Sevda group which included, among others, Maffy Falay (t), Salih Baysal (v, vn), Okay Temiz (d, pc) and Rosengren. With Bengt Berger contributing mridangam and tabla to several tracks, the musicians on Notes From Underground ranged from Rosengren himself, Tommy Koverhult (ts), Bobo Stenson (p), Torbjörn Hultcrantz (b, pc) and Leif Wennerström (d, pc) to Falay (t, darbuka), Baysal and Temiz.