Nothing could be more unlike a jazz musician’s life than a weekend break in Cornwall, especially if the musician is black and even knowing there’s a well-known jazz club at the Western Hotel in St Ives. In Justin John Doherty’s award-winning film, jazzman John (James Barnes) is chasing a romantic interlude with a white girlfriend, Alice (Katharine Davenport). They are in love – explosive, unexamined, physical love. In their seaside cottage, they clearly aim to consummate it. In the past they’d probably have no sooner bonked than he’d be off on his travels again, in nocturnal flights like the one they take at the start of the film. Driving to Penwith after a gig in Luton is probably a bad idea forced on the pair by the musician’s lifestyle or his notion of a surprise. Love unpolluted is, and turns out to be, a distorting mirror.

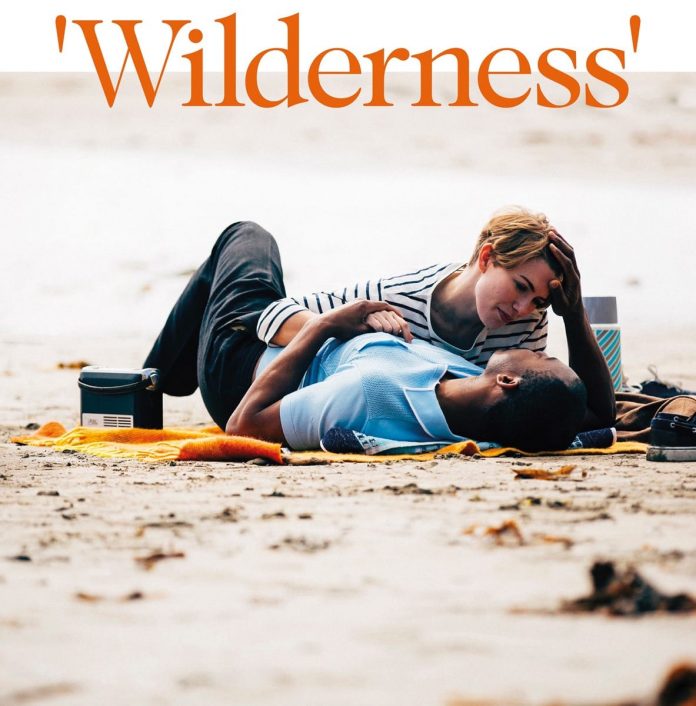

The first thing about Wilderness that will strike home for anyone, like me, who has spent innumerable holidays in Cornwall is the realisation that all the visitors down there are white. It’s one of those casual observations made only when issues of race are being considered. John and Alice spend their first morning alone on a beach, where they are caught in flagrante delicto by a dog being walked by the beach’s owner. It’s not so much embarrassment for the owner but an opportunity for him to express his authority and his distaste. That he directs himself at John as a black man with a white woman in tow and by extension at Alice as a white woman in the company of a black man, and shagging him al fresco to boot, is barely concealed. It’s a beach to which John and Alice as the cottage’s occupants have access. Later, access to a rocky cove cut off by the tide is, as they say, pregnant with meaning.

A bad start, not least for Alice, who would prefer to let the beach incident pass, thereby discounting John’s legitimate grievance. John later announces casually that the pair are to spend an evening nearby with his musician mate Charlie (Sebastian Badarau) and his partner Frances (Bean Downes), who have opted for permanent domicile in the fastnesses of Lyonesse. Charlie, a former jazz drummer who drums professionally no more, has opted for teaching, one of Cyril Connolly’s “enemies of promise”; Frances is – well, unhappy in the wilderness. Alice is unhappy because John didn’t tell her that anyone would be sharing their weekend or that the other pair even existed, or that … well, watch the film. The time seems indeterminate: John drives a classic Volvo, Charlie plays a chunky, Grundig-like tape recorder, though life in West Cornwall even today can be time-warped.

Like a classic Volvo on a slope with a dodgy handbrake, things slide further downhill, to a jazz accompaniment. And like a lot of other film soundtracks, some of it is hard to recall. That’s the problem with background music: it’s in the background. Maybe that’s where it plays its essential part. There’s no mistaking the prescient intro – Ornette Coleman’s Lonely Woman, performed by the Tony Kofi Quartet (Kofi, Byron Wallen, Larry Bartley and Rod Youngs, but only their instruments shown). Elsewhere there’s a “Love Theme” – Gaetano di Giacomo’s Conceria Hills – performed by the New Land Trio of Gaetano, Emilio Merone and Jason Simpson; Crossing My Fingers by Alex Webb and Sharleen Linton; The Offering by Renato D’Aiello, the London-based Italian saxophonist, and played by him; and a few tracks from the album Good Cop, Bad Cop by the Damon Brown Quartet (from Brown, Jonathan Gee, Yorai Oron, Yaaki Levy, Idit Eshel and Shai Zelman). A pivotal scene incorporates Michel Legrand’s music for the 1962 film Eva. Paul Jolly, the film’s jazz consultant, chose expertly.

One approaches films about jazz and jazz musicians with trepidation. They’re too often littered with clichés. But it’s soon clear that Wilderness is only nominally about jazz and race, and little about race anyway. That, even for a jazz fan, may be its prime virtue. Directed with a light but sure touch to a sharp Neil Fox script, the interactions and revelations of John and Alice are universal. The four principals do everything to make their characters and their slice-of-life situation achingly real. Jazz just gives them an edge, as jazz often does. As obbligato to a fractured idyll, it expresses its wretched side and finally hymns a resolution of sorts.

Wilderness, a film by Justin John Doherty. Sparky Pictures; Baracoa Pictures; colour; 84 minutes; available as stream or download