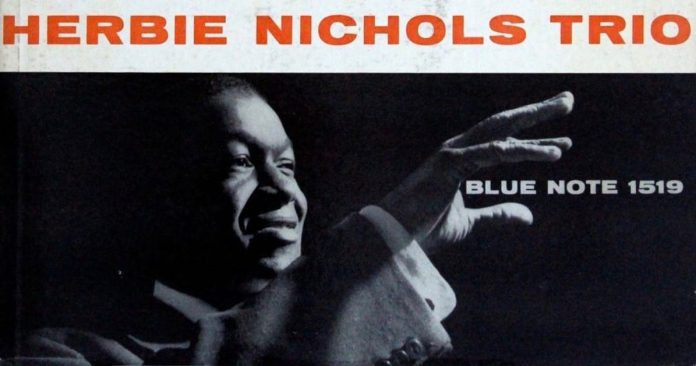

Herbie Nichols might not have known much about marketing, but then marketing in his day consisted of not much more than a few trade ads, a little positive coverage from critics who often regarded themselves as tastemakers, and word of mouth.

This wasn’t necessarily emblematic of a more innocent world. It was, rather, a sign of a world in which it was, to put it simplistically, acknowledged that “jazz” was a relatively esoteric form of art music that commanded a small but loyal audience, and probably always would.

That audience situation hasn’t changed, but the same isn’t true of the marketing. Meanwhile, the social bubble in which musicians who claim to play jazz exist these days is radically different, and potentially more damaging than anything Nichols knew.

As a pianist and composer with a well-above average originality in his methods, Nichols was hardly primed to crossover into any bigger market, lucrative or otherwise, and the lazy comparisons with Monk which were the most some of those tastemakers could muster for him didn’t serve him well.

A. B. Spellman was an honourable exception to that rule. His description of Nichols as “a talent that was too subtle for the casual listener and too demanding for the lazy improviser” (1) is not only as good a brief summary as there’s ever likely to be, but also with the benefit of perspective a means of highlighting how the marketing “industry” deals only in sweeping generalisations.

Right now, they’d have us believe that because there’s currently a double figure number of young musicians (one or two of them even with major label contracts) who claim to playing jazz, the music is in a robust state of health.

This little phenomenon happened in the 1980s, when both Courtney Pine and Andy Sheppard landed contracts with Island Records’ offshoot Antilles. Their prominence then and their survival since says something about their commitment, but that initial burst of enthusiasm was arguably just a snapshot of ephemeral significance. This may prove to be the case with the present recurrence regardless of how much more sophisticated and pervasive the marketing is.

Herbie Nichols’ music still stands alone, by the way, just as impervious to the blithe rhetoric that’s now an integral part of the marketing of music. Even more, it seems to show a similar imperviousness to the greater existential concerns that now move us all.

(1) From the booklet essay in the Complete Blue Note Recordings (three-CD set)