From quite early in the 20th century Sidney Bechet had an affinity with France and all things French, finally deciding to settle there at the end of the 1940s. This caused great relief all round among New York’s jam session musicians, for Sidney had for many years been regarded as a pain in the ass.

There were several reasons for this disrespect, but the main one was Sidney’s ever-presence. It seemed that, if there was a jam session or a concert anywhere in the city, Sidney would turn up, sit in and take it over, to the automatic exclusion of any other soloists who might have been looking forward to having a go. Sidney appeared to have been very bossy, although without having had any authority invested in him.

He was of course one of the all-time giants of the music, being held in the highest respect by Duke Ellington and of course by Bechet’s main disciple, Johnny Hodges. Not so with Louis Armstrong, though. Sidney was three or four years older than Louis and no doubt, with seniority being so important in New Orleans, regarded himself as superior. But they got off to a good start.

They met when Louis was 11 and Sidney 14, and Sidney remembers being so impressed by Louis’s musical talent that he invited him home for dinner. Always quick to take offence (as I know from personal experience) Sidney was to hold a grudge for life after Louis failed to turn up for the meal.

It’s quite possible that Louis was nervous about befriending a Creole – something that at that time didn’t usually happen in New Orleans. Later the two played an advertising job, with just a drummer accompanying them. Louis was paid 50 cents.

It’s likely that, in the early days of the 20th century, Sidney was more musically eloquent than Louis and no doubt disparaged Louis as the trumpeter reached and surpassed Sidney’s stature during the 30s. By that time neither man appreciated the other, as was made plain during the wonderful session that produced 2.19 Blues and Perdido Street at the session on 27 May 1940 for Decca/Brunswick. This was a glowing meeting of majesties, but each man then and later expressed dissatisfaction with the other.

“He didn’t play what he said he was going to play,” cavilled Bechet, although why that should have bothered him, who was going to get on with his own playing and not take any notice of Louis anyway, is not handed down to us. He did give Louis credit on rare occasions, as when he spoke of Louis playing the clarinet solo from High Society on the cornet.

“It was very hard for a clarinet, and really unthinkable for a cornet to do, but Louis, he did it.”

“Jazz”, Sidney said, “is a name given to the music by white people.”

He and the other musicians spoke of “ragging” tunes, and thus “ragtime” which covered the whole genre and not just the mechanical piano music.

Sidney’s main influence was Big Eye Louis Nelson and he took lessons from him when still a boy. Sidney was playing professionally before he was 14. At that stage he avoided learning conventional technique, believing correctly that “inspired improvising” would carry him through.

Having dispatched the local pikes, it was amazing that the Bechet shark allowed the musical tadpole that was Mezz Mezzrow to wriggle about in his aquarium.

But hang on. We’re following the accepted run of logic that has, for a century, said that Mezzrow wasn’t any good.

“Mezzrow was usually a dreadful musician,” wrote the lamented Richard Cook. John Chilton, benign and brilliant author, suggested that Mezz was “essentially a folk and blues musician for whom conventional technique was irrelevant”. “That”, continued Cook, “hardly excuses playing of often diabolical ineptitude on most of his records: rarely has such a prominent jazz man left such a dispiriting legacy of play.” Richard was obviously holding back.

When I was four or five my dad, who led his own professional-standard string quartet, used to play often a 78 of Mezz’s Hot Club Stomp and The Swing Session’s Called To Order. I thought it was great stuff, and was of course unaware that Mezz was being bolstered by Sy Oliver and Jay C Higginbotham on that record.

I grew up listening to lots of Mezz, including the weekly dose of Gettin’ Together by the Mezzrow-Ladnier Quintet that served as the signature tune for the jazz record programme presented by that inexhaustible mine of misinformation, Rex Harris.

Hugues Panassié, premier lunatique complètement fou of the French jazz scene, wrote: “Mezzrow is by far the greatest clarinettist that the white race has produced.” Fazola, Goodman, Shaw, Fawkes, DeFranco? Ils sont petits garçons.

Mezzrow, who had an intellect that in some respects matched that of Goofy in the cartoons, came to believe that he was black.

Nonetheless there is a large catalogue of good jazz records that have him present, and giants like Bechet, Benny Carter, Teagarden and Waller seemed to be happy to record with him.

What Mezz was good at was being a fixer. He could persuade record companies to record him and his friends, and in doing this he provided a service of inestimable value, whether it be in recordings with Tommy Ladnier or Teddy Wilson.

Fats Waller and Louis Armstrong were amongst the raft of musicians who valued another of Mezz’s services – he was the main provider of marijuana to the New York jazz community. In the earliest years of that operation the drug was legal. When it became illegal Mezz was smartly despatched to the slammer, insisting, he claimed, to be incarcerated in the prison reserved for black men. (Louis and Mezz remained friends for life. Such was Louis’s affection for his hemp provider that Mezz became Louis’s manager for a short time.) And nobody could question Mezzrow’s love of jazz, which was his life-force. Another of his devoted friends was Bix Beiderbecke, who upset Mezzrow when he became interested in the music of Stravinsky. Presumably terrified, Mezzrow insisted that they should just play the blues.

Bechet, who was a giant virtuoso, was sought out by record producers, even though he didn’t during the 30s, make more records than Mezz did.

“I’m not saying that Mezzrow is all that bad a player,” he said. “When a man is trying so hard to be something he isn’t, when he’s trying to be some name he makes up for himself instead of just being what he is, some of that will show in his music, the idea of it will be wrong.”

Mezzrow had a lifelong obsession with Bechet’s music that had begun in 1918 when he first heard Sidney, who was then playing in the Original New Orleans Creole Jazz Band. At that point, in Chicago, Bechet and King Oliver must have just replaced George Bacquet and Freddie Keppard in the band, which later mutated into King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band.

Mezzrow reached another peak with his recording career in Paris in the early 50s. I haven’t heard most of the tracks, but I’m sure there could have been none better that the session on 2 April 1953 with superb playing from Buck Clayton that produced Wrap Your Troubles In Dreams/Rose Room.

Perhaps it was the old pals act that prompted Lionel Hampton to invite Mezzrow to his most productive jam session recording for Vogue in Paris on 28 September 1953. Hamp used a homogenous septet from his touring big band, and added Mezz, and a the odd French musician. Hampton’s men were all junior boppers and Mezzrow stuck out like a grafted thumb. But, with his talent for adapting himself the results were all right, and he rode the general informality with some success. Hampton’s choice of guitarist Billy Mackel and electric bassist Monk Montgomery for his band had been inspired. This was one of Lionel’s most exciting bands and the result was a most enjoyable day in the studio that was probably appreciated more in France than elsewhere.

Mezzrow followed Bechet by settling in Paris in 1950, where he stayed until his death on 5 August 1972.

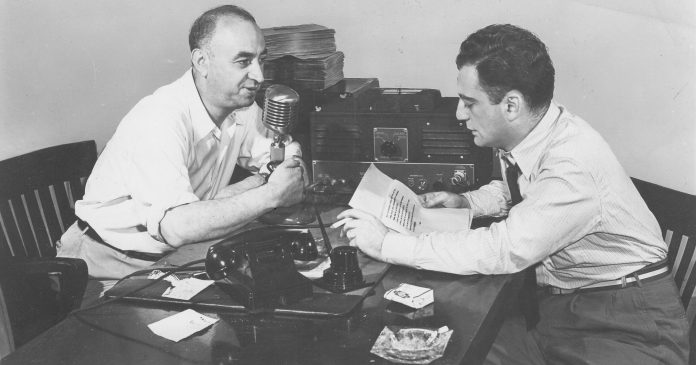

Photo: Mezz Mezzrow (left) and his biographer Bernard Wolfe. By Bob Smith