Albert Ayler was a free-jazz saxophonist that made even Ornette Coleman look old fashioned. When he arrived on the scene, a short time after Coleman, the jazz press and public were just not ready for his radical sound.

He had a sound that was as big as a house and a way of improvising at times that blended tones into one big mixture that disregarded individual notes. He was as free as they come in avant-garde jazz, yet his themes were at times a mixture of gospel, folk and even simple nursery rhymes. His vibrato was so broad that many compared him with Sidney Bechet and his combo was often said to be similar to a traditional New Orleans ensemble. He was a strange mixture of very futuristic jazz one minute and going back to the roots the next.

Ayler was a mass of contradictions, says Kolada. What he said one minute was unlikely to be the same the next and his response also depended on whom he was talking to.

The author compares Ayler’s story with Greek tragedy, and with good reason. The tragedy was the lack of recognition and success in his own land and his early and mysterious death. He was found floating in the Hudson River in New York City, aged just 34.

Ayler made a significant impact on free jazz and on its development. But although he was hailed as a genius in Europe, he never made much impact at home in his lifetime. Peers such as Coltrane, Cecil Taylor, Eric Dolphy and Coleman became household names but Ayler’s influence, as Kolada points out, was greater on rock musicians.

Ayler was, according to the author, the inspiration for John Coltrane’s avant-garde explorations and Trane often talked with him and listened closely to what he was doing. Kolada reports stories of them playing together in concert and on one occasion, Coltrane placing a chair front and centre of the stage to sit and listen closely to everything Ayler was playing.

Crucial to the Ayler story though, is the relationship between him and his brother Donald. Many reports claim Donald Ayler was an accomplished saxophonist, equal to or even superior to Albert. However, both their father and Albert himself persuaded Donald to learn trumpet and play in the saxophonist’s band. At first it worked well even though Donald Ayler was never able to match up to the sympathetic and stimulating way his predecessor Don Cherry had performed with the band. Eventually, the story goes, Albert felt that he had to replace Don and the guilt he felt about that and Donald’s mental problems that followed tipped him over the edge into suicide.

There are conflicting stories about Albert’s state of mind and the way he behaved prior to his death. He seems to have had his own mental breakdown and was talking about flying saucers attacking and making other strange pronouncements. All sorts of wild speculation followed his death, but what remains certain is that Ayler was a major saxophone innovator.

Kolada’s book traces his life and music from birth in Cleveland, USA in 1936 to his death from causes unknown in 1970. His narrative is clear, precise and includes passages quoted from notable jazz writers such as Dan Morgenstern, Valerie Wilmer, Barry McRae, Nat Hentoff and many more. This book seems to trace almost everything jazz folks need to know about Ayler and a bit more besides.

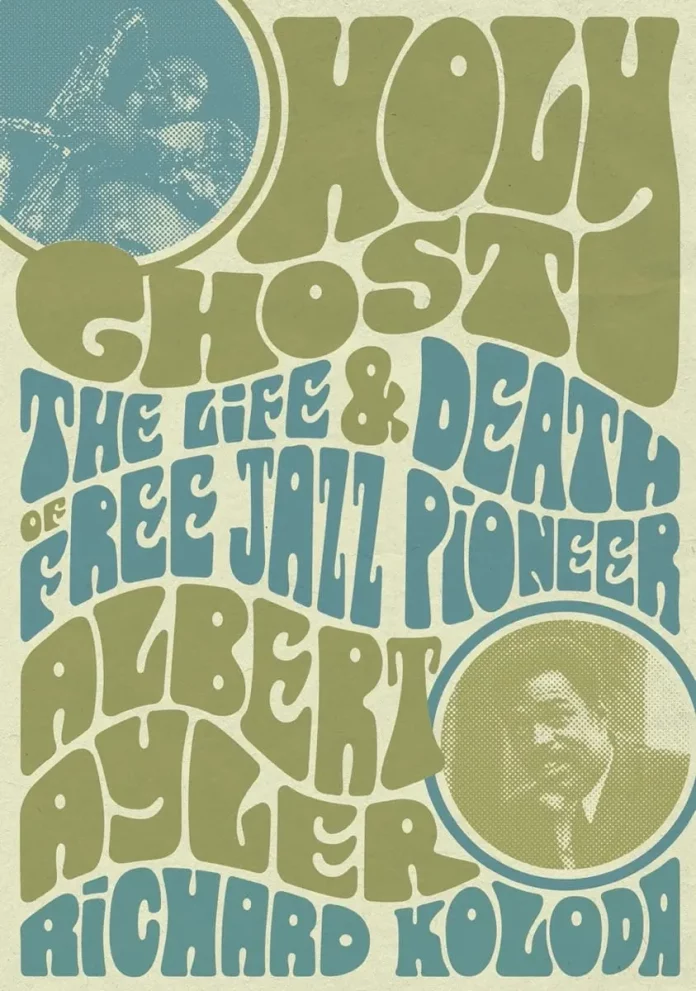

Holy Ghost: The Life & Death Of Free Jazz Pioneer Albert Ayler by Richard Kolada. Jawbone Press, London, 302pp, pb, £14.95. ISBN 978-1-911036-93-7