The original mule

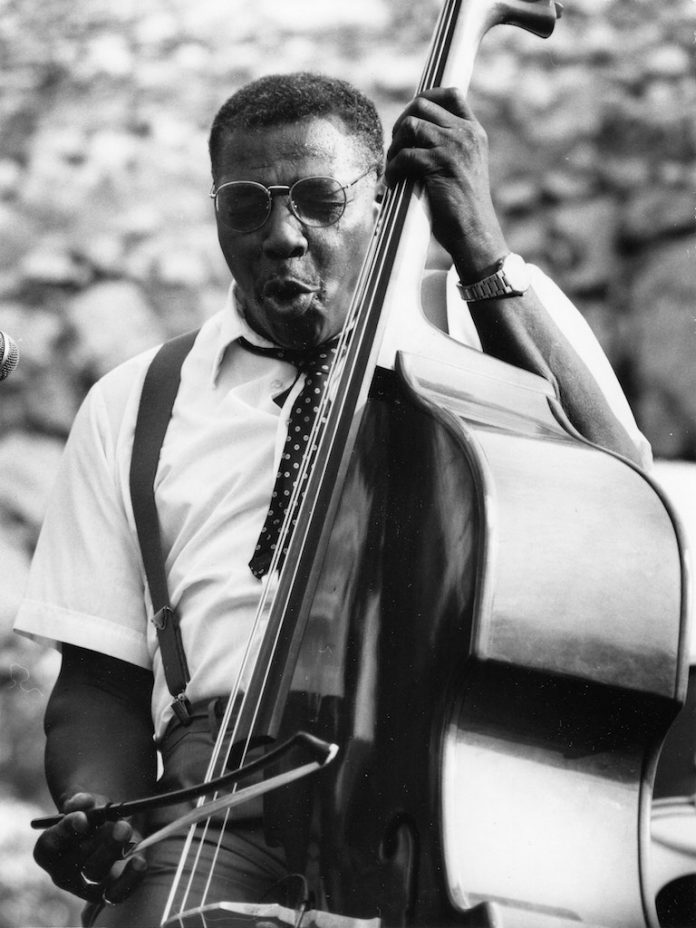

Major “Mule” Holley was a most original bass player, who readers will perhaps remember, along with his sterling work as an accompanist, for his dazzling and eccentric feature with The Kings of Jazz on Angel Eyes. It was played arco with unison vocal and usually with grotesque quotes from Pagliacci and other opera sources.

Major didn’t become a bass player from choice. He became a professional violinist in 1938 when he was 14 and joined the most prominent symphony orchestra in Detroit, led by LeRoy Smith. When he was called into the US Navy in 1942 and deposited into a navy band he owned up to some familiarity with the tuba and bass horn.

“They wanted a bassist. I was obliged to play the bass. They said that if I didn’t I’d be sent to dig in the garbage pits”.

That must have been some navy band. It included embryo jazz stars like Clark Terry, Gerald Wilson, Ernie Royal and Osie Johnson. It was Clark Terry, when he saw Major carrying both of his instruments at once, who remarked that he looked like a pack mule.

‘Ever since it was revealed to me how vulnerable they are by an incident many years ago, I have always remembered the members of the royal family in my prayers’

Clark had a penchant for good nicknames, and “Mule” stuck with Holley until his death.

Later, in another navy band, Major roomed with alto player Willie Smith.

Royal manoeuvres

Ever since it was revealed to me how vulnerable they are by an incident many years ago, I have always remembered the members of the royal family in my prayers. The incident occurred at a concert given in the Royal Festival Hall some decades ago. Fortunately on this occasion there was no would-be assassin involved.

After the concert the bandleaders and a couple of star American musicians who had all taken part were to be presented to the Prince of Wales. Everyone else was cleared from the backstage area by security and the appropriate leaders were assembled into a carefully ordered queue.

The singer Beryl Bryden had not appeared at the concert, at least on stage, but she had acquired a ticket and was in the audience. Somehow, amazingly for such a large personage, with a manoeuvre both deft and surreptitious, she got backstage at the time of the ceremony. Prince Charles had relaxed conversations with each of the bandleaders as he progressed along the line. When he reached the end of the line he found Beryl, who stuck out her hand in greeting and had a brief but significant chat with him.

Roy and Diz – combative jazz

Norman Granz was intelligent enough to make a lot of money out of jazz, and democratic enough to share it with his musicians to improve their quality of life and standards of living. I went down to London for the two concerts given when he brought one of his later Jazz At The Philharmonic presentations there. One of his groups included the Oscar Peterson rhythm section with Dizzy Gillespie, Clark Terry and Roy Eldridge – just the three-trumpet front line. I was lucky to have plenty of time to talk to Norman backstage. The three trumpets had just finished blazing away. Norman told me what he required of them. “When they go on stage I want blood”.

“But surely”, I asked him, “players of the calibre of Roy and Dizzy are too mature for that kind of cutting concert?”

“You’re joking, of course”. Clark Terry’s eyebrows shot up as he answered for Granz. “You’ve just named the two most competitive musicians in the world. Playing with those two is the hardest thing I’ve done in years because they just never let up. You’d better not be off-form or ill or anything when you play in that league because they’ll be on you like a shoal of piranha fish”.

“This is why Diz and Roy work for me so often”, Granz said. “They’re able to continuously keep up a razor-sharp standard of playing which is both unpredictable and inspired. That kind of staying power goes with being a jazz prime-mover – and both of them are”.

Fast, but saying nothing

Roy was one of the main inspirations for Gillespie in his early days and yet, unlike Dizzy, Roy was erratic and could surge between tasteful playing and extreme flashy in a few bars. Even as he exploded into high-note flash, he knew he was destroying his earlier good work. I was with him after a concert in Southport many years ago when he expressed his remorse.

“Being fast and playing high is nothin’, man. What I like is to play ballads. Listen, now this is very important. This is what I learned from Louis Armstrong. If anybody writes a book, there has to be an introduction to the book, right? To tell you what the story’s about. Then they go on and write a book and it works through to its logical climax. It develops logically and gradually. Now in my early days my playing was fast as greased lightning, but I couldn’t tell a story. Chick Webb told my brother Joe ‘he’s fast, but he ain’t saying nothing’. I couldn’t play a ballad. But I can now”.

“You must have been the first really high note player”, I suggested.

“No”, he said. “Tommy Stevenson in the Lunceford band used to play altissimo Ds and things like that. What I did was to play complete riffs up there, but I couldn’t get as high as him with single notes. In fact I was smothered as early as 1931 by Rex Stewart. My highest note then was about an A and I never dreamed there was a B flat above that. We had a battle one night and Rex laid it on me”.

Volatile and irritable

In 1941 Roy joined the otherwise white band led by the amiable Gene Krupa. He suffered from racial victimisation while out on the road, and this eventually made him volatile and irritable, a condition that led to the break-up of his amicable and musically successful relationship with the band’s singer, Anita O’Day. Roy left the band when he had a nervous breakdown. He joined another white band, that of Artie Shaw, in 1944 but similar treatment led to his departure from Artie. He said “As long as I live in America, I’m never going to work in a white band again”.

He remained volatile and Buck Clayton told me of an incident in Paris when the band were on tour with the Jazz From A Swinging Era unit in 1966.

Apart from the two trumpets, the band included saxophonists Earle Warren, Budd Johnson, Bud Freeman and pianist Earl Hines. It was meant to be a band of equal mainstream stars. But as the tour went on, Earl Hines pushed himself to the forefront and gradually began introducing the players and numbers as though it was his band.

This really infuriated Roy, and every time it happened his blood pressure soared a little higher than it had the time before. Earl, who had used exactly the same method when he was a member of the Jack Teagarden All Stars (they even transformed into the Jack Teagarden-Earl Hines All Stars during the tour), remained unaware or more likely impervious to Roy’s outrage. By the time the group played in Paris the trumpeter had decided to walk out. It was only assiduous and persuasive counselling from Buck that kept him on board.

After Roy suffered a stroke in 1980 he displayed his prowess as a jazz singer, but didn’t play any more trumpet before his death in New York on 26 February 1989.

Bowl of flowers

When he first moved to Paris in 1949, Sidney Bechet shared a flat with Claude Luter’s drummer Moustache Galipedes. On one occasion Sidney was using the lavatory when an idea came to him for a tune. He called to Moustache to bring him his soprano sax. The drummer handed it in through the door. After a few minutes of blowing a new melody resounded around the flat.

“That’s beautiful”, said Moustache. “What are you going to call it?”

“Petit Fleur”, said Sidney.

Listeners to that great theme today are perhaps not aware that “poser les fleurs” (“planting the flowers”) is a Gallic colloquialism for defecating via a bowel movement.

Tough Teddy

It must have been her at times half-hearted approach to her career that stopped Teddy Grace being better known to jazz history, for she was an outstanding singer of her time. “Half-hearted” in the sense that she occasionally left her career and returned to it later, rather than that she wasn’t intense about it when she sang. In fact she could be a tough cookie in the studio.

Jack Teagarden and Billy Kyle played on her second recording date in September 1938. Both were by then well-established stars who seem to have appeared on the studio date for union scale to help out the young singer – they would normally have been paid more.

It was not unusual for the musicians to booze on such occasions, and this session was well-endowed with bacchanalian accelerators. Tea, always a fine accompanist, plays well behind the lady on the four tracks that were done, but she seems to have thought that she could hold her liquor more efficiently than he did. As he slumped to the ground against one of the legs of the piano, Teddy, far from overawed by the trombonist’s reputation, left, after asking Kyle to tell “that damned Indian” when he woke up that while she thought he was a good musician he couldn’t drink worth a damn.

Although it is a mistake commonly made, the Teagardens were of German and Dutch descent, and had none of what we must now refer to as “native American” blood.

‘Kapp disliked any kind of improvisation on his records and wanted songs sung as written. He had steam-rollered the jazz out of Bing Crosby’

Teddy’s recording contract with Decca was an oddity in itself, for on the face of it she was not the kind of singer who would attract the attention of Jack Kapp, the man who ruled Decca’s collection of artists with an iron needle.

Kapp disliked any kind of improvisation on his records and wanted songs sung as written. He had steam-rollered the jazz out of Bing Crosby (it was he who fostered Bing’s profitable Irish and Roman Catholic leanings and stomped on Bing’s scat). He’d also reeled in the improvisations of contracted singers like Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald and Connie Boswell. Teddy probably benefited from her friendship with Kapp’s right-hand man Bob Stephens, a man who had a very high opinion of her voice.

Teddy, who sometimes appeared in cabaret and could sing pop songs attractively with her very melodic voice, was basically a jazz singer who very much preferred blues, almost certainly anathema to Mr Kapp. But, probably with persuasion from Bob Stephens, he commissioned from her a blues album for Decca and, on titles like Downhearted Blues, Gulf Coast Blues, Graveyard Blues and the like, she showed herself much more adept at interpreting the songs than any of the classic blues singers had been. The blues came so naturally to her that when the album was finally released in 1939 listeners who hadn’t seen her assumed that she was black. Billy Kyle backed her again, this time with his pals from the John Kirby band Buster Bailey, Charlie Shavers and O’Neil Spencer.

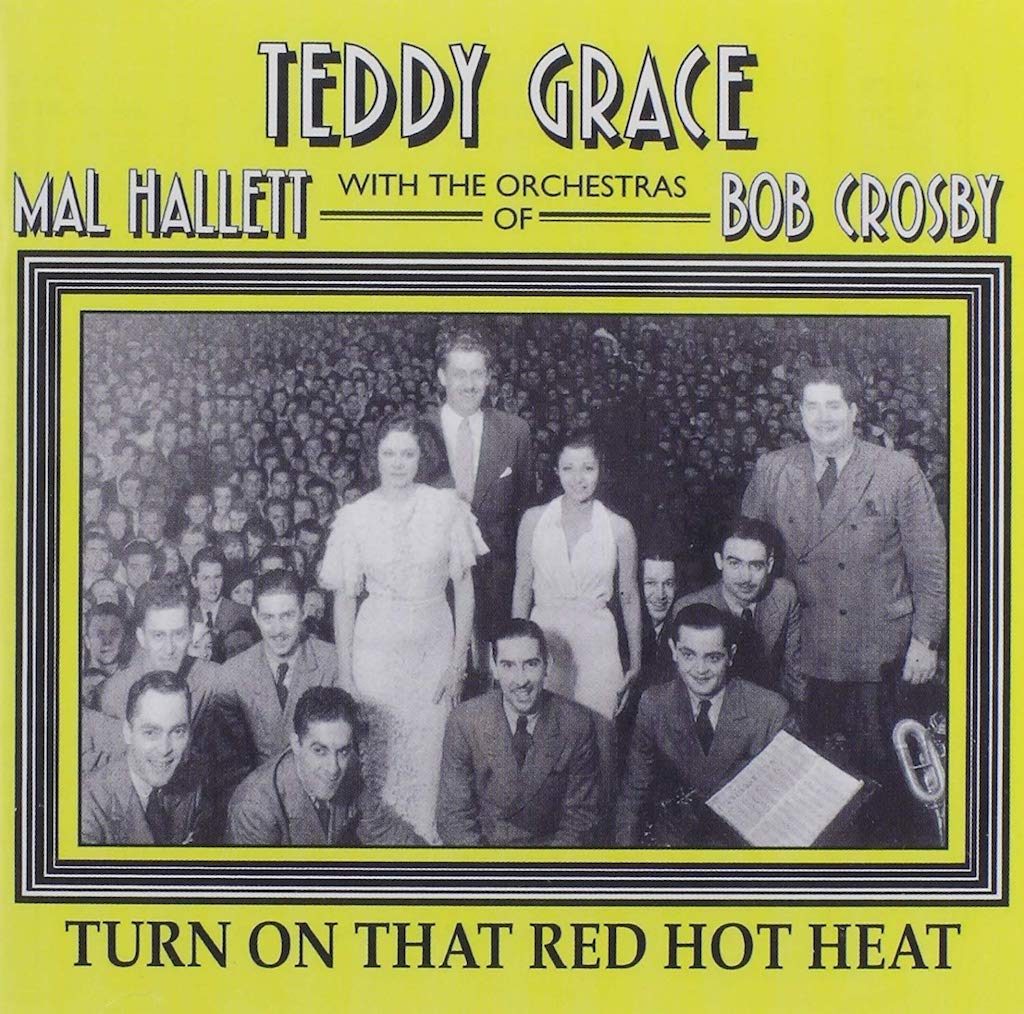

The 1938 tracks with Teagarden and Kyle along with the blues album, originally on five 78s, make up part of the 22 tracks on the fine CD Teddy Grace on Timeless CBC1-016, deleted but still available on Amazon for £39.99 – does anyone actually pay such ridiculous prices? Much more reasonable are the 26 tracks on Turn On That Red Hot Heat – Teddy Grace on the still available Hep CD 1054 for £7.30. Red Wagon on the Hep album has nice blues feeling. The Mal Hallett charts are very much of their time – accomplished but now dated, and the ones done when she was Bob Crosby’s studio singer have pleasing jazz bits from Fazola, Miller and Butterfield.

Glamorous and very attractive, Teddy, who was born in Arcadia, Louisiana on 26 June 1905, had a hard beginning. Her mother and father, victims of the Spanish flu epidemic, died within days of each other when she was 14. When she was 18 she married a divorced company manager whose job meant travelled a lot. She went with him.

Her singing career began in 1931 in Montgomery, Alabama, where she had settled with her husband. She was with friends one night listening to a band at a local country club. The band was broadcasting on a remote and she was in the audience singing quietly along with it when her friends dared her to go up and sing over the mike. She ran onstage and began singing St Louis Blues. Her success seems to have been instant, and within no time she had regular spots on each of the local radio stations.

After work with a couple of local bands she joined the Boston-based territory band led by violinist Mal Hallett in February, 1934. Despite the “band vocalist” tag, her popularity with audiences soon looked like overtaking that of the band itself.

‘Her outstanding looks and personality meant that she was to marry twice more’

Unhappily a car accident in 1935 on the way to a gig released all the tension that had built up within the singer, and it seems as though she may have had a nervous breakdown. It may have been connected to her husband’s refusal to travel on the road with her instead of she with him. Whatever the reason they divorced. Her outstanding looks and personality meant that she was to marry twice more.

Hallett tempted her back to work when, in 1937, the band was booked for a season at New York’s Commodore Hotel, from where it was to make regular broadcasts. These were so successful that the contract with Decca followed and the 10 sides that Teddy recorded with Hallett are included on the Hep set. Kapp was so pleased that he gave his blessing to the Decca session in 1938 with Teagarden and Kyle.

Fellow-Decca artist Bob Crosby was without a singer in 1939, and Teddy worked with his band in the studio, but declined to go on the road. Ten of the tracks she did with Crosby are on the Hep issue.

Her last commercial session was with Bud Freeman’s Summa Cum Laude Band in 1940. At the end of it Bud, impressed as always by a beautiful lady and by a good singer, asked her if she’d like to do more work with the band.

“I’m sorry, Bud”, she said, having now fallen out with Decca, “but I’m sick of the whole business. This is the end for me”.

‘She was transferred to clerical work and, following her discharge in 1946 moved to Los Angeles where she married her third husband and worked as a typist’

It wasn’t quite. In 1943 she enlisted in the Women’s Army Corps, where it was realised that her singing career and familiarity with audiences would fit her ideally for the job of recruiting soldiers to the army. She proved indeed to be very good at the job, and organised variety shows and bond rallies and soon found that she was singing more than she had when she had been with the bands.

As a result, in 1944, her voice disappeared completely and for six months she was unable to make a sound. She was transferred to clerical work and, following her discharge in 1946 moved to Los Angeles where she married her third husband and worked as a typist.

She was tracked down in 1991 by her biggest devotee, David McCain (he wrote the liner notes for the Timeless and Hep CDs), and in her old age took satisfaction from the news that collectors still sought her recordings.

Teddy Grace died on 4 January 1992.