By 1952, the big bands winding down and bebop’s rough edges getting smoothed out, jazz appeared poised on the verge of a Golden Age. Many of the swing stars were still around, and playing better than ever. Modern jazz thrived in New York, Los Angeles and other cities, sparked by any number of fine players and arrangers. In an era when the King of Bebop recorded with strings, and the King of Swing fronted bop bands, anything seemed possible. It was also a time of post-war prosperity, audiences having money to spend.

Crow found himself in the centre of all this activity, and thanks to his determination, dependability, avoidance of drugs and possibly a little luck, began getting calls. After Stan let him go in 1953, he worked for a time with Claude Thornhill’s band. Thornhill was a decent leader, and Bill enjoyed his music. He was also a bit eccentric. Recalled Bill in 2019: “He loved having a band … and his book was very musical. But if he started to get a hot record, he’d take a month off and go fishing, or something. He didn’t like having to do interview shows and things like that.”

In 1954, following gigs with Terry Gibbs and Jerry Wald, Crow ended up in the Marian McPartland Trio along with Joe Morello on drums. This was a musically rewarding experience for the self-taught Crow: “She really improved my playing a lot just by playing in a lot of hard keys – she loved to modulate.” He worked with Marian, off and on, for several years. Their classic Capitol album At The Hickory House was actually recorded at the Capitol Studios, the band being perplexed by the poor state of the piano there. The trio reconvened for a follow-up (live) album – called, appropriately, Reprise – for Concord in 1998. This time Marian played a satisfactory piano.

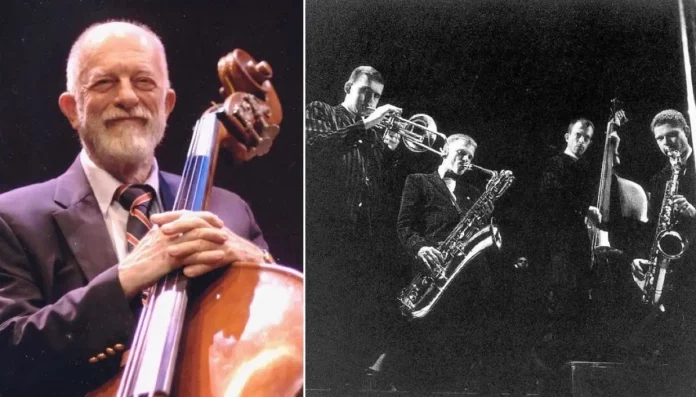

Crow’s next major association began late in 1955 when he joined Zoot Sims, Bob Brookmeyer, Jon Eardley and Dave Bailey as the newest member of Gerry Mulligan’s sextet. For the self-taught bassist, some of Gerry’s charts proved difficult to play. Realising he needed to learn proper bass technique, especially fingering and using the bow, he hooked up with Fred Zimmerman. Then principal bassist with the New York Philharmonic, Fred turned out to be an excellent choice, and Crow made rapid progress.

Bill worked off and on with Mulligan for 10 years in what may have been the baritone great’s most productive period. “The music was always wonderful,” Bill told me in our 2023 chat. He went on to explain how the sextet evolved: “After we did a European tour with that group, Zoot stayed in Paris for a little while and Jon went to Florida, so we were a quartet with Brookmeyer. Then I left, and he called up and said he was starting a new group with Art Farmer, and [asked] would I like to be on it.” Gerry was then invited to appear in a Hollywood movie with the quartet, but Bill – having fallen in love with Aileen – decided to stay in New York.

After he returned from California, Gerry was keen on forming a big band. Crow says “He thought he’d do more writing if he had a big band. So he had two versions of that group, and finally he turned the straw-boss job over to Brookmeyer who finalised the personnel of that band; Zoot didn’t want to play in the section, but they got him to come along as a featured soloist, and they did a European tour. Then Clark Terry and I joined the band, and that was really a wonderful band.” This version of Mulligan’s Concert Jazz Band recorded an album for Verve at the Village Vanguard that rates as one of Crow’s favourites: “That was a good glimpse of how good that band was.” Gerry disbanded the group when Norman Granz sold Verve, negating the financial arrangement Gerry had made with Norman. Says Crow, “But we loved the band so much, that once a week we’d get together and rehearse, and once in a while we’d do a week or two at Birdland, or something.”

In 1962, Benny Goodman hired Crow for his highly publicised tour of Russia. Goodman assembled an impressive group of stars, among them Joe Newman, Joe Wilder, Jimmy Maxwell, Phil Woods, Zoot Sims, Jerry Dodgion, Jimmy Knepper and Mel Lewis. Likewise, Benny had a cache of new charts by the cream of New York arrangers: Ralph Burns, Al Cohn, Jimmy Knepper, John Bunch, John Carisi, Tadd Dameron, Gary McFarland and others. As Crow writes in a long piece on his website: “We had rehearsed it all thoroughly in New York and had it sounding good.” But as the tour progressed, Benny refused to feature the new charts often, favouring his warhorse standbys from the 30s, a disappointment to the band that had laboured hard to master the challenging new arrangements. Benny also proved himself rather thin-skinned. When an inspired Phil Woods outplayed the old man one night, turning in a magnificent solo that left both audience and band awestruck, Goodman was not pleased. He never called that particular chart again on the entire tour. He was conceited, aloof, occasionally irascible and rude, and his boorish behaviour began to alienate most of the musicians. Crow is unequivocal in summing up the tour: “During my brief time with him, I watched him completely demoralise an excellent band.”

Well established on the scene by the 60s, Crow had little trouble finding work at that time. When the opportunity arose, he joined the house band at Condon’s, a good combo with Dave McKenna, Peanuts Hucko, Yank Lawson, Cutty Cutshall and Morey Feld. Toward the end of 1965, Bill and Aileen wanted to buy a house in Rockland County, just north of the Jersey border, 20 minutes from Manhattan. A regular gig at the Playboy Club promised a steady salary, so he took it. At the club, he worked with Walter Norris, a fine jazz pianist, though not all of the music they were asked to play was jazz. However, the gig was flexible, allowing him to work outside jobs with old friends like Zoot Sims and Bob Brookmeyer.

With jazz gigs drying up in the 70s, Bill ended up in pit bands on Broadway, along with scores of good jazz musicians looking for financial security. It wasn’t always terribly fulfilling, but it paid the bills. And there were chances to play jazz on occasion. In 1980, Crow retired from Broadway, “back to jazz” as he puts it.

And jazz is blessed to have him back. Near the end of our 2023 chat, I asked what he considered his strengths as a bassist. His answer provided clues as to why his services have been sought by so many for so long: “Well, I have good time, and I know how to get a good sound out of my instrument. I’m pretty good at choosing notes for the bass line that move the harmony in a nice way. I got used to doing that without any help, especially on the Concert Jazz Band [where] there was no piano… It just comes from listening. I listen to everything that goes on around me and try to find something appropriate.” What musician doesn’t want to hear that from a colleague or an accompanist?

These days, Mr. Crow is all over Facebook, generously sharing stories of his remarkable life with his many friends, fans and admirers, including those, such as myself, he has never met in the flesh. Ask him about any musician active in the last seven decades, and it’s a safe bet he’ll have a story. (Readers wanting to know more about Bill are encouraged to seek out Neal Miner’s excellent recent documentary, Jazz Journeyman, available on YouTube. Crow’s official website is also a good resource. A number of Bill’s writings may be accessed there.)

More than 70 years since he first descended the stairs to Birdland as a dues-paying musician, handed Pee Wee Marquette his dollar bill, and took to the bandstand, Bill is still listening, still creating, still tailoring his bass lines in the moment, making the band sound good. And still telling stories. Indeed, if a more inspiring story than his exists, I have yet to hear it. He lives as a reminder of a world he helped to create at a time when the planets seemed to align, leading to a great flowering of American musical culture – Bird, Bud, Dizzy, Klook, Max, J.J., Miles, Stan, Zoot, Al, Sarah, Billie, Buzzy, and the rest. Their innovations gave us the soundtrack for the modern era. William Crow knew them all, and they knew him. What an honour to have this man among us.

See part one of Bill Crow: journeyman bassist and master storyteller