Blues and soul performer Bobby Rush reflects that it took him over 50 years to become an overnight sensation. This is the paradox that is Bobby Rush. In many respects he led the most stereotypical of lives to become a blues singer – born in the deep south of America, picking cotton as a young child with his family of sharecroppers, making music on makeshift instruments and growing up in circumstances where his colour would limit the opportunities available to him.

Yet Rush – even as a young child – was never suppressed by his circumstances. He constantly looked for opportunities, whether to find better ways to pick cotton and make more money, play the guitar better or join a minstrel show to develop his performing talents. He was a musical sponge, eager to absorb not only the traditional blues music that came from previous generations but the new R&B sounds that were coming from the likes of Little Richard and Bo Diddley.

Where Rush defied the trend was in not moving too far away from his native south and playing the chitlin circuit for most of his professional life. The chitlin circuit was a collection of clubs, theatres and bars running from New Orleans and Florida in the south all the way up to Chicago in the Midwest and along the east coast up to New York. These clubs provided commercial and cultural acceptance for black musicians, comedians and entertainers during a time of strict social segregation in the United States.

Unlike his blues contemporaries, Rush rejected opportunities to tour Europe and Asia or sign to bigger labels. He was a man with a plan; and whilst it may have had geographical limitations and severely restricted his exposure to the record-buying public and national radio stations, it was his plan.

That is not to say life was easy for Rush. He defied death on a couple of occasions: he was shot as a youth and nearly killed when his tour bus overturned on the way home from a gig. He also experienced the death of two of his children due to hereditary illness.

For most of his career he never had the money that greater exposure would have given him and he relied on income from a local take-away food store he set up to supplement his musical career. He was let down badly by musical colleagues – including James Brown – and producers and learned the hard way not to rely on others. He managed his own bookings, drove his own tour bus, funded his own recordings and promoted himself to local radio stations and club owners. You could say that he was so successful in doing this within the environment of the chitlin circuit, that he had no need to explore further. Even when he moved to Chicago, he would still spend most of his time back in the deep south on tour; prompting him, eventually, to leave Chicago and move back to Jackson, Mississippi.

If you had to define Bobby Rush’s style it would probably be as a cocktail combining the earthiness of John Lee Hooker, the eloquence of B.B. King and the showmanship of James Brown. His skills on the harmonica are also amongst the best.

Whilst the blues runs through Rush’s blood, he believes in putting on a show for his audience, with an MC, dancers and plenty of humour. This may sound more like revue than the blues and is clearly a consequence of his long experience on the circuit where he would perform with comedians and entertainers as well as other musicians. But his acclaimed showmanship has earned him a reputation second to none in the clubs and bars that have booked him year after year. Nor was he afraid of straying from the blues into soul, R&B and in later years into funky blues.

The recording successes were few and far between in the early days and only in later years have his albums been given the critical recognition and commercial success they deserve with Grammy awards for Porcupine Meat (2017) and Rawer Than Raw (2020) – plus five other Grammy nominations. Since 1997 he has received 51 nominations for Blues Music Awards and was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2006. This recognition has clearly had an impact on the way Rush now sees his career and he has at long last started to travel abroad to festivals as well as signing up with specialist blues label Rounder Records.

Now aged 87, Rush is one of the last men standing. Throughout his many years performing he has befriended and worked with legends such Muddy Waters, Otis Rush, Buddy Guy, B.B. King, Ray Charles, Little Walter and many more. He is the bridge that straddles the time from when the blues moved from the country to the city and then subdivided into numerous sub-genres such as R&B, soul and funk.

This is a fascinating story told in a highly personalised style without the need for lengthy chapters or strict chronology. When he has something to say, he says it. It is a simple as that and he ain’t studdin’ ya. Well worth the read for all blues fans and historians.

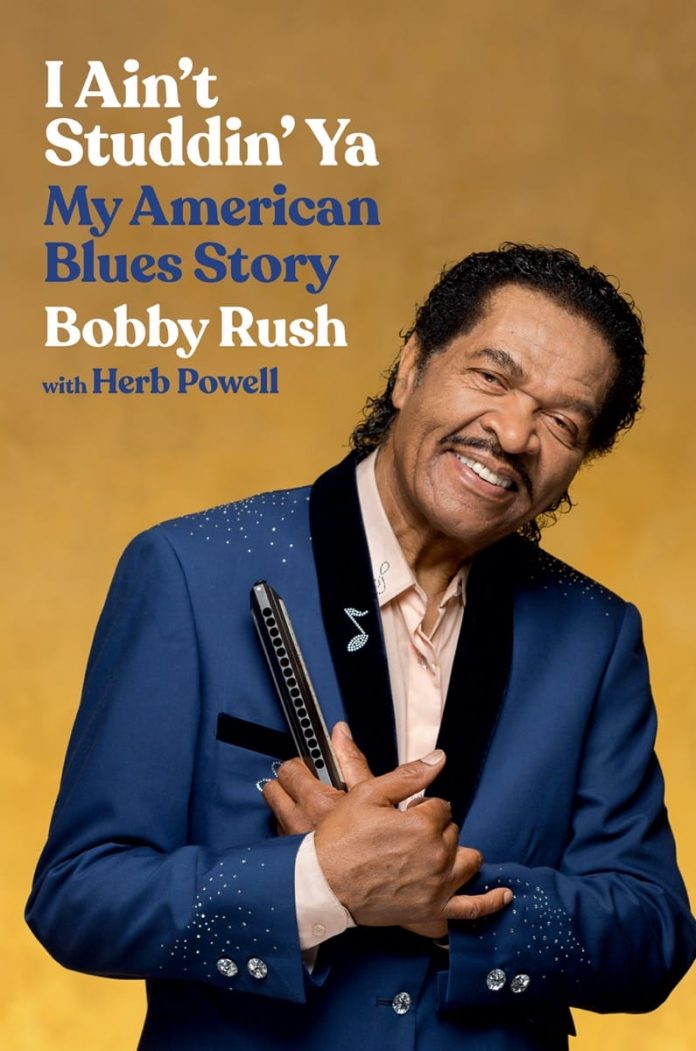

I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya – My American Blues Story by Bobby Rush (with Herb Powell). Hachette Books, 306 pp, hb, £25.