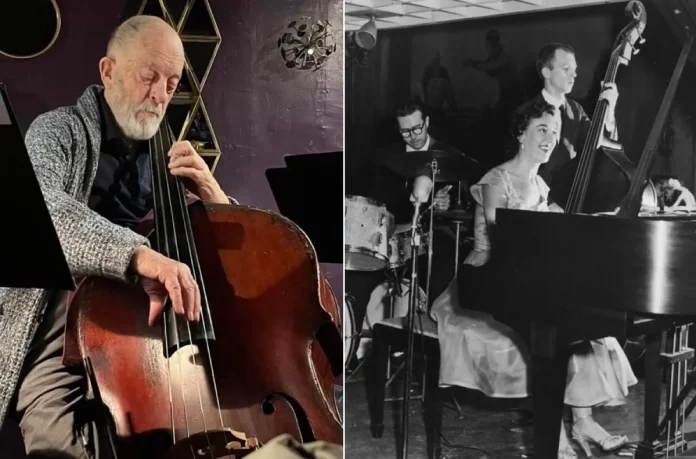

Bassist and author Bill Crow claims a direct link to the originators of modern jazz. As he relates in the very first sentence of his autobiography, “Birdland was my alma mater.” Although he had studied music briefly at the University of Washington, his real education began in 1950 in the New York club bearing Charlie Parker’s nickname. There he sat at the feet of Parker and cohorts with an eye (and ear) to mastering this exciting new music that had sparked his passion. “The illustrious professors there were some of the world’s finest jazz musicians,” writes Crow of those long-ago days. Many of the masters he dug at Birdland can be identified by a single name: Bird, Bud, Diz, Miles, Max, J.J., Lucky, Milt, Red (Rodney), Fats (Navarro), and many more. For a youngster from the distant West Coast, these were heady times.

A scant two years later he was playing Birdland himself, sharing the same stage as his “professors.” This auspicious start would afford him opportunities to contribute to the rhythm sections of numerous jazz giants. Those whose working bands have benefited from Crow’s strong pulse and unerring time feel, his ability to play melody and tell a story with a solo, his dependability and positive, uncomplicated nature include Stan Getz, Gerry Mulligan, Bob Brookmeyer, Benny Goodman, Claude Thornhill, Terry Gibbs, Marian McPartland, Vic Dickenson, Don Elliot, Gene Di Novi, Kai Winding, Jim Hall, and Eddie Condon, to name but a few.

Since the early 50s, he has appeared on numerous recording sessions as a sideman. His extensive discography lists nearly two dozen live and studio dates with Mulligan, about a dozen with Getz, four each with Zoot Sims and Bob Brookmeyer, plus dates with Al Haig, Marian McPartland, Clark Terry, Sam Most, J.J. and Kai, Jimmy Cleveland, Milt Jackson, Sal Salvador, Ruby Braff, Phil Woods, Annie Ross and many others.

Somehow he found time to pursue a career as a writer, producing short works of fiction along with articles for publications such as Gene Lees’ Jazzletter. He has also authored two books on his life in jazz. The first, Jazz Anecdotes, appeared in 1990, a well-crafted and highly entertaining collection of musicians’ tales. A patient and aware observer with remarkable recall, Crow invests his stories with telling detail and demonstrates a deft touch in developing characters. Jazz Anecdotes was followed by From Birdland To Broadway, Crow’s acclaimed autobiography. As with his first book, the memoir is wonderfully detailed, creating a vivid narrative that brings the decades-old events he describes to life.

When Tetsuo Hara, president of Venus Records, learned that the books had been translated into Japanese by Haruki Murakami – one of Japan’s leading novelists – he proposed that the author make separate CDs to accompany each of them. Crow obliged, releasing his first leader albums on the Japanese label, choosing musicians he felt comfortable working with. It’s a crack band: Carmen Leggio on tenor sax, Joe Cohn (Al’s son) on guitar and David Jones, drums. Of this quartet, Bill told me in a 2019 telephone interview: “Well, that was Carmen’s band. He had a little once-a-week gig that we played and when he could get Joe Cohn, he always did. And David Jones is a drummer that we both loved that lives up here. So I just grabbed those guys and wrote out some tunes and we made them.”

A few weeks shy of his 96th birthday as I write this, Mr. Crow enjoys robust mental and physical health and remains active on the NYC jazz scene. In 2019, I asked him who he was working with: “I’m playing with people a third my age mostly. There’s a trumpet player named Ryo Sasaki who calls me for gigs down in Soho and Tribeca… There’s a good tenor player named Chris Johansson – young guy – that calls me for occasional jobs.” I phoned again in November 2023 for an update: “There’s a club over in Brooklyn that I play with some people about two or three times a month. Then there’s a place out in Staten Island where the band has the first set, and then there’s a jam session.” And Crow still works with his friend, Ryo Sasaki, in a quartet at Smalls, a popular Manhattan jazz spot.

William Orval Crow began life in the last few days of 1927 in Washington State, about as far from Birdland as one can get in the contiguous United States. He explained to me how the jazz bug bit him as a youngster: “My sixth-grade music teacher called me into his house as I was walking by one day and said, ‘I want you to hear something.’ And he played me Louis Armstrong’s West End Blues, and that really converted me into being interested in jazz. I thought, ‘Oh, there can’t be anything more wonderful than that.'” Inspired, he began collecting every jazz 78 he could lay hands on. “The electric store in this town that I lived in – Kirkland Washington [near Seattle] – had a stack of records in the back that you could listen to – not just the Victors and Columbias and Capitols, they had a whole lot of small labels, so I was introduced to people like Mary Lou Williams and Eddie Miller and Casa Loma Orchestra while I was still in junior high school, so I just stayed with it until I could play it myself.”

Starting out with piano lessons from his mother – a music teacher – he soon switched to trumpet and then to baritone horn, his main axe throughout high school, and later, during a stint in the army. He also became proficient enough on drums to play them on occasional gigs. By the time of his permanent move to the Big Apple in January 1950, Bill had graduated from baritone to valve trombone. He had yet to touch a bass.

Wayne L. “Buzzy” Bridgeford proved the catalyst that set him on the path to the Apple. A colourful, larger-than-life eccentric, the ill-fated drummer from Olympia, Washington had already served in the bands of Stan Getz and Claude Thornhill, and had appeared on record with the Randy Brooks Orchestra. Back in Washington State in 1949 to convalesce from a serious automobile accident, Buzz convinced Crow – who had been gigging around Seattle and Tacoma – that moving east was essential if he wished to make a career of music. [Buzzy struggled with heroin addiction until his death in 1956. The official cause of death was pneumonia.]

In New York, Crow haunted Birdland and Charlie’s Tavern – the legendary jazz hangout – making contacts and seizing every opportunity to get in on a jam session or a paying gig. (One contact from Charlie’s, Dave Lambert, introduced him to Aileen Armstrong, who later became his wife of 53 years until her passing in 2019.)

Running low on cash, Bill found himself unable to pay the admission charge at Birdland. “That didn’t keep me away from the place,” he writes in his autobiography. “I’d go there every night and stand half way down the stairs where I could hear the music, even if I couldn’t see the band.” He took a $30-a-week job at a printing firm and lived as cheaply as possible, eating simple meals and sharing rooms with other musicians. With the little cash left over, he began lessons with Lennie Tristano and stayed focused on his goal of becoming a professional musician. His friendship with Dave Lambert led to his first recording date, a group vocal session on two numbers by Mary Lou Williams, but the records were not released at the time. (They have since appeared on CD with some other Williams material.)

When Buzzy Bridgeford invited him to join a small group he had assembled in the summer of 1950 to play at a hotel in the Adirondacks, Crow hitchhiked to Tupper Lake and met the drummer. As with his move to New York, Bridgeford was the key to Crow abandoning valve trombone in favour of the bass. Needing it for his quartet, the persuasive drummer insisted Bill learn to play the plywood bass he had rented. He learned on the job, by trial and error. After returning to the city, Crow discovered the advantage his new skill afforded him, writing in his autobiography, “There wasn’t much happening for a valve trombone player, but I occasionally found a Saturday night job on string bass.”

Back in the city Crow played whenever he could, doubling on valve trombone and bass. Money was scarce, but he endured poverty for the occasional gig. One such was playing Monday nights at Birdland – on the same stage as his idols – when the regular band was off. Another was a Toronto gig with vibraphonist Teddy Charles. In Toronto, Bill got a taste of the big time when he filled in one night for Dizzy Gillespie’s bass player. Dizzy subsequently hired him to play bass for a one-nighter in Buffalo, and then offered him a job with his band. Not wanting to leave Teddy Charles flat, without a bass, Crow reluctantly told Dizzy no.

While still with Teddy Charles, the budding bassist was hired by Jimmy Raney for a gig with Stan Getz, at the Hi-Hat in Boston. After the one-week engagement, Stan invited Bill to join his band, and they opened as the Birdland headliner. In his book, Crow notes the audience included every bass player in New York who wasn’t working: Mingus, Pettiford, John Simmons, Tommy Potter, Gene Ramey, Curly Russell and Clyde Lombardi. “I never faced a tougher audience than the one at Birdland that night,” declares Crow.

Though he loved Stan’s playing and enjoyed his company when he stayed away from heroin, Crow admits in his memoir that “when using drugs he could be awash with maudlin sentiment one minute, and cold, distrustful, and cruel the next”. I asked Bill how he managed to deal with Stan when the tenor man was in a funk or stoned. “Well, like Zoot said, ‘He was a nice bunch of guys.’ He took a little advantage of me, but I was single at the time, and I didn’t mind. We’d go on jobs and he’d get drunk, and I would drive him home and stay overnight with him and his family – he was living out in Levittown then. He had two little boys, and I liked his wife – she was very nice.” Stan, on the other hand, was no gentleman with the ladies: “He was very handsome and very appealing, so he had a lot of women flocking after him, and he treated them all terribly, including his wife.”

But in the main working with Getz was good, one result being classic recordings such as the sides produced by Norman Granz in 1952 that were later released as Stan Getz Plays. Indeed, Stan plays, beautifully, on some lovely standards. The band is first-rate: Duke Jordan on piano, Raney on guitar, Crow on bass and Frank Isola on drums. The music still sounds fresh more than 70 years on.

See part two of Bill Crow: journeyman bassist and master storyteller