The author has chosen the work of five musicians, all African American improvisers, to illustrate the use of music and improvisational skills in addressing social inequalities and affirming humanity.

Trumpeters Terence Blanchard and Ambrose Akinmusire claim to use improvised music to make commentary on systemic and structural racism expressed in police brutality. Drummer Terry Lynne Carrington tries to address racism and gender inequality through her collective approach to “social-science music”. The final pair are pianist Andrew Hill and drummer Billy Higgins, although Williams claims their performances are not as explicit or openly political.

The author’s expression “crossing bar lines” is intended to suggest what he calls “the metaphorical connection between African American musicians’ use of unconventional and ‘experimental’ music strategies and their articulation of Black musical space”. He adds their musical performance of social action in that space. He goes on to say that he uses “crossing bar lines” as a metaphor for black performative insurgency in sound for the purpose of expressing black humanity. Many people reading this book will no doubt be pleased that he made that clear.

Williams takes pieces of music by these musicians, analyses the recordings, comments on them and draws his conclusions. He goes into each selection in great detail, quoting from the words of the five musicians themselves, other commentators and even refers to Barack Obama’s 14 December 2012 speech in the wake of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Connecticut. Williams claims that Blanchard’s album Breathless was a response to the tragic killing of Eric Garner, a black man being held down by a New York City policeman whose cries that he couldn’t breathe were ignored and led to his death. The suggestion is that Blanchard used examples of breathing, inhaling and exhaling in producing his music, using, in effect Black Musical Space. The spaces in the musical performance indicate breathlessness. That is an oversimplification and readers will need to read this book in full to understand the full scenario. Williams does make it clear that Blanchard is not articulating only black despair but the experience of many who are oppressed and relate to the “continuing historical and structural siege of Black bodies”.

The same thorough analysis of works by Higgins, Akinmusire, Carrington and Hill is done, with examples of their individual recordings. In Carrington’s case, her work takes in gender inequality as well as recognition of all oppressed people of all creeds. For Andrew Hill it was all about non-conformity and avoiding the conventional articulations of musical blackness in codified jazz forms. His sense of black musical space was in his non-acceptance of musical conventions and his way of bringing street-music theory to life and playing original, uncategorisable music that was totally unique. Hill always claimed to be non-political and non-conformist.

This book was first published in 2021 but I am assuming it was finished before the death of George Floyd and the conviction of Derek Chauvin. That was, I believe, the first time a white police officer was convicted and sent to prison for the unlawful killing of an unarmed black man. A sign of change and justice for all people in the future, perhaps.

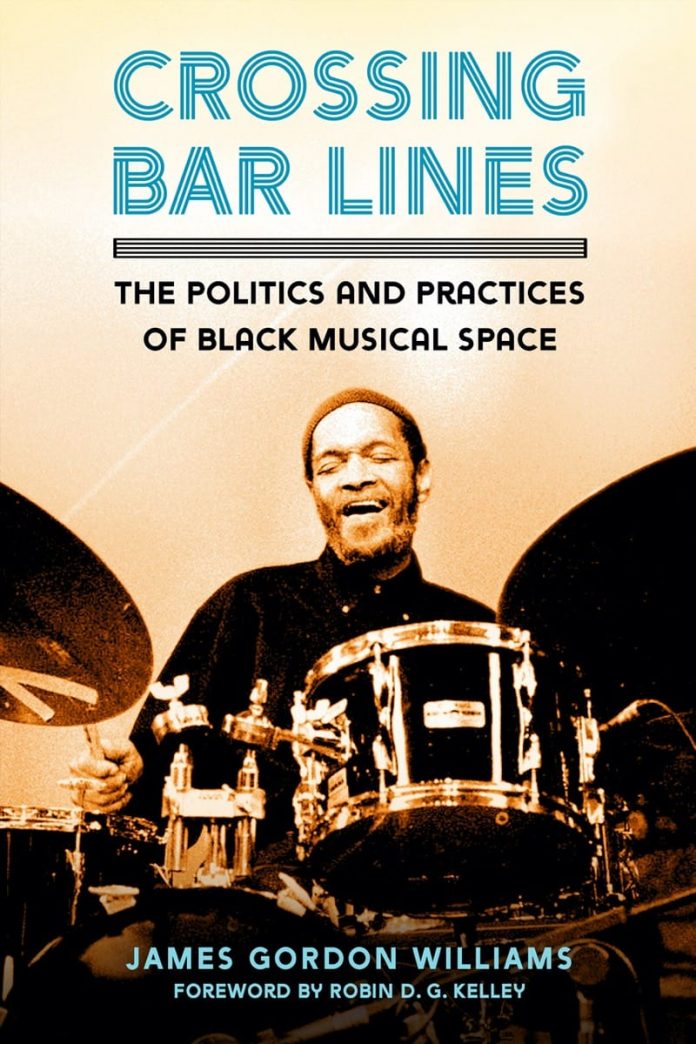

Crossing Bar Lines – The Politics And Practices Of Black Musical Space, by James Gordon Williams. University Press Of Mississippi; pb; 204pp, 10 musical examples. ISBN: 9781496832115