The news of guitarist Jeff Beck’s sudden death early this January, from bacterial meningitis, brought shock and grief to many. Tributes to the inimitable master of the Gibson Les Paul, Fender Telecaster and – especially – Stratocaster flowed from, e,g., Stevie Wonder, Jimmy Page, Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood, Eric Clapton, Joe Satriani and Steve Winwood. And in the mainstream British press a range of articles complemented appreciative obituaries, all underlining the uniqueness of Beck’s voice in the evolving history of the electric guitar.

In the DVD Still On The Run: The Jeff Beck Story, Clapton – who regularly invited Beck to his annual Crossroads blues festival – says “Not that many rock players ‘get’ jazz. But Jeff does!”

Beck’s life will not be reprised in any extensive detail here: the journey from what Beck called the “net-curtain land” of suburban Surrey to Wimbledon School of Art and a career that took him – via The Tridents and The Yardbirds, The Jeff Beck Group, Beck, Bogert and Appice and any number of collaborations (with musicians of the calibre of Jan Hammer, Max Middleton, Tony Hymas, Jason Rebello and Vinnie Colaiuta) – to an historic manor house in East Sussex, a world-class collection of hot-rod cars (which he often built himself) and the biggest stages the world over. Rather, I’d like to look at Clapton’s remark in terms of what it might suggest to a jazz-inclined ear and mind.

For the Norwegian guitarist Terje Rypdal, in the 1960s Beck and Clapton stimulated his generation to ponder the power and the poetry of how contemporary electric guitar might sound. Decades on, Rypdal’s fellow guitarist and ECM recording artist David Torn worked (under the pseudonym Splattercell) on production matters of several tracks on Beck’s Jeff from 2003. With its blend of savage riffs and vocalised hot-rod mythology, programmed electronica, deep lyricism and the blues, Jeff has two of my all-time favourite Beck pieces in Seasons and JB’s Blues – while for Torn, Beck was “one of the only electric guitar players who has the whole electric guitar sound in his hands”. But does any of this make Beck any sort of a jazz – as opposed to a blues or rock – guitarist?

The response of the British press to Beck’s death included brief consideration of mid-1970s jazz-rock Beck albums such as the best-selling Blow By Blow and Wired (both produced by George Martin). But there was no mention of Performing This Week: Jeff Beck at Ronnie Scott’s (where Clapton guested on some numbers, as did vocalists Joss Stone and Imogen Heap and the Big Town Playboys). Recorded at the back end of 2007, the two-CD release featured such classic items as Beck’s Bolero, Stratus, Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers, Nadia, Goodbye Pork Pie Hat, Brush With The Blues, Angel (Footsteps) and Where Were You. It documented what Beck called “the happiest week of my life”.

One (prime) reason Beck was so enthused about the five nights he played at Ronnie’s was the quality of the quartet he led, with Jason Rebello (kyb), Tal Wilkenfeld (elb) and Vinnie Colaiuta (d). In the interview he gave for the DVD recording of the engagement, Beck spoke admiringly about new Australian recruit Wilkenfeld (born 1986) – “so young but already so great, like Jaco [Pastorius]”. Wilkenfeld herself has had some interesting things to say about Beck and jazz, underlining the melodic strengths of Beck’s playing: “I was always a fan of instrumental music, jazz and fusion, things like that. But Jeff’s stuff is extra special. It maintains dynamics, great composition, melody and sheer musicality all the time. Sometimes, jazz can ignore some of that ‘song sensibility’.”

If there is a most affecting strain of lyricism in Beck, evinced by such pieces as (Nitin Sawhney’s) Nadia, Where Were You, A Day In The Life, Seasons, Declan and Over The Rainbow – as well as his various Little Wing concert tributes to Jimi Hendrix or his readings (on the 2010 Emotion & Commotion) of Puccini’s Nessun Dorma and Britten’s Corpus Christi Carol – there is also an extraordinary, at times seemingly unbridled element of primal power to his work, as in, e.g., Hammerhead, Freeway Jam and Big Block.

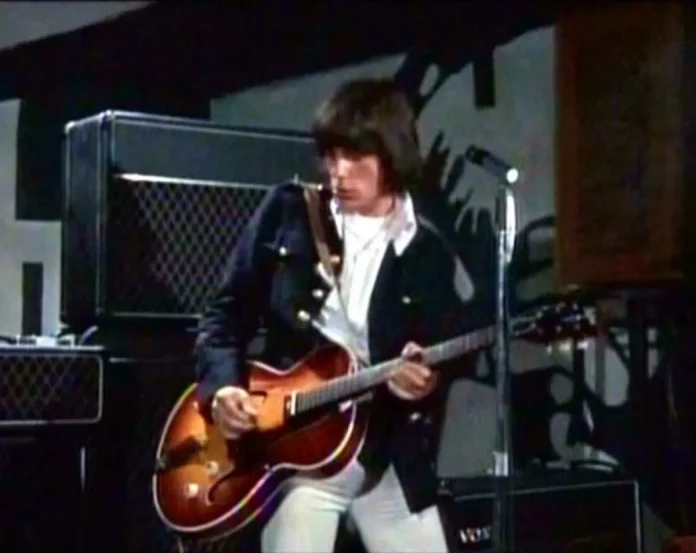

For U2 guitarist The Edge, Jeff Beck was both “punk rock before punk existed and one of the most inventive guitar players of all time”. The first part of this assertion can be quickly substantiated. Hear, e.g., the urgent repeated figures in the “key-challenging” soloing by Beck on The Tridents’ 1965 live version of Bo Diddley’s Nursery Rhyme (available on the three-CD Beckology collection from 1991). Or see, in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 Blowup, Beck’s Pete Townshend-like trashing of his guitar after thrusting it into a malfunctioning amplifier – while the Yardbirds (with Jimmy Page on board) keep rocking, on The Train Kept A-Rollin’. The second part of The Edge’s assessment repays more sustained investigation.

As good a place as any to begin is a comment from composer and keyboardist Jan Hammer, who appeared many times with Beck and in 1977 cut the lively and atmospheric jazz-rock item Jeff Beck With The Jan Hammer Group Live. In Martin Power’s Hot Wired Guitar: The Life Of Jeff Beck (2014) Hammer speaks of his work with Beck on Hammer’s Blue Wind from the slightly earlier Wired.

As Hammer puts it, “Jeff really listened with the right attitude [and we] really made it work … within that improvisational jazzy sort of rock beat.” The definitive example of that sort of beat would come later, in the relaxed yet driving intensity of the compelling interplay captured on the surpassing Jeff Beck: Unofficial Bootleg USA ’06 with Jason Rebello, Vinnie Colaiuta and Pino Palladino (elb) – the penultimate track of which is Blue Wind, missing from the track listing details of my Japanese import edition.

In Annette Carson’s Jeff Beck: Crazy Fingers (2001) Hammer observes of Beck that “He’s the only person of his type – which is a genuine 1960s rock and roll guitar hero – who actually advanced anywhere beyond the ’60s. You take every one of those other guys, from Clapton down to Page and Wood or whatever – they are still sitting where they started, haven’t moved one inch. But Jeff progressed incredibly, because he’s open to all kinds of melodic invention.” How much, one wonders, did the fact that, in Clapton’s pithy words, Jeff Beck “got” jazz, play a key role here?

In a Guitar School magazine analysis of Beck’s solo on Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers from Blow By Blow, the guitarist and educator Wolf Marshall suggests that “Jeff delivers the melody and fashions the improvisations like a jazz saxophonist would, with great subtlety and drama, unflagging attention to dynamics, detailed shadings of tone colour, phrasing nuances and contrasts, and a wide range of expression.”

Like a jazz saxophonist would? Beck himself once declared “I’m not a jazz guitarist. No way. I consider myself a rock guitarist. If they want to hear jazz they can dig out a multitude of albums and stack them up to the ceiling. But what I’m doing ain’t jazz! […] All I’m really playing is elaborated blues with progressive rock overtones.”

One might agree, if one’s awareness of Beck’s music extended only to, say, the proto-Led Zeppelin Truth of 1968 with its core personnel of Rod Stewart (v), Ronnie Wood (elb) and Mickey Waller (d) or the 1973 double CD Beck, Bogert And Appice Live where at times the spirit of Cream is in the air.

However: Beck’s comment can only be seen as a typically modest and deflecting take on his own abilities, given the deep and wide-ranging poetics of an art rooted in such an open-minded love and knowledge of music as it was. After all, this is the man who – in the aforementioned interview for the DVD of Performing This Week: Live At Ronnie Scott’s – spoke most warmly of the many marvellous nights he had spent as a listener at Ronnie’s, including one especially memorable occasion when he and Jan Hammer heard and spoke to Elvin Jones.

This is the man who, all his life, remembered the early magic of hearing both a snatch of blues on his uncle’s car radio and the sound of the electric guitar on How High The Moon, by Les Paul and Mary Ford, as it came out of the family radio. And this is the man who, on Stevie Wonder’s Talking Book of 1973, played the exquisitely cast, mellow yet also nimble and chromatically inflected solo on Looking For Another Pure Love. Some see this as evidence of the early impact of Barney Kessel on Beck and for our editor Mark Gilbert the track offers “ the best evidence of Beck’s jazz-ability”. One might also mention here that it was some drumming figures from Beck, improvised while he was waiting in the studio, that laid the basis for Wonder’s smash hit Superstition (which Beck himself would record twice, with Tim Bogert and Carmine Appice).

The point to underline is that the breadth and the depth of Beck’s capabilities, sensibilities and elective affinities enabled him to go on to shape a body of work where jazz is present in many a register, signifying both what jazz has been and what it might become. Think of Savoy from Jeff Beck’s Guitar Workshop With Terry Bozzio And Tony Hymas – which Annette Carson characterises as “a stylised shuffle with Buddy Rich boogie/bebop overtones” and which Beck himself saw as having “a ’40s-type swing, pre-rock ’n’ roll”. Or sample the combination in many a Beck concert performance of the Mingus blues Goodbye Pork Pie Hat (which was dedicated to Lester Young) and pianist Tony Hymas’s intriguing, spaciously constructed and dynamically subtle Brush With The Blues.

Beck’s influences, or affinities, ran as wide and deep as his many contributions to other people’s projects (ranging from Mick Jagger, Tina Turner and Stanley Clarke to Narada Michael Walden, Herbie Hancock and Roger Waters). They included Cliff Gallup, lead guitarist for the rockabilly 1950s group Gene Vincent and the Blue Jeans, and Les Paul: Beck celebrated their music, respectively, on the 1993 Crazy Legs and the 2011 Rock’n’ Roll Party: Honoring Les Paul. BB King and Buddy Guy were also centre stage in the picture: check Beck’s appearances on King’s DVD Live By Request, Guy’s Damn Right, I Got The Blues and his presence (along with Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top, another Beck favourite) on Beck’s Live At The Hollywood Bowl of 2016. And don’t miss the tasty YouTube piece which has BB King at The Apollo in 1993, in the company of Beck and Clapton, Guy and Albert Collins.

Also consequential for Beck – who listened to a lot of classical music – were Steve Cropper and Motown. Hear the take by Rod Stewart and Beck on Curtis Mayfield’s People Get Ready, one of the best features, alongside the dive-bombing guitar solo on Ambitious, from Beck’s Flash of 1985 (perhaps his least satisfying album as a whole, with its underwhelming programmed drum figures). Further Beck favourites ran from Django Reinhardt and Lonnie Mack to James Brown and Bob Marley (hear Beck’s Caribbean take on the Beatles’ She’s A Woman, from Blow By Blow) to Ravi Shankar and the Bulgarian State Television Female Vocal Choir. The last-named inspired Beck’s extraordinary creativity with the whammy bar and harmonics on Where Were You from Guitar Workshop, which became a standout feature of his concert performances.

In Mike Figgis’s superb documentary Red, White & Blues, available in the seven-DVD boxed set The Blues, A Musical Journey assembled by Martin Scorsese, Beck is present. There are also contributions from, e.g., BB King, Chris Barber, John Mayall, Eric Clapton, Pete King, Chris Farlowe, Van Morrison, John Cleary, Davy Graham, Georgie Fame, Peter Green, Tom Jones (with whom Beck riffs and raps) and Lulu (with Beck contributing to her fine version of Cry Me A River). There are many memorable concert appearances by Beck available on DVD and YouTube. But this study of the emergence of British blues in the 1960s and the subsequent British “blues invasion” of America offers the most intimate and special documentation of Beck both playing and speaking.

Evincing a quiet modesty and an evident passion for and knowledge of the blues, Beck talks of how important the “bent note” of the blues was – and remained – for him: “a sort of major/minor thing” as he puts it. If he was a master of bottleneck playing, especially at the demanding top end of the fretboard, the influence of the pitch-bending and sliding sitar is evident in Beck’s early work for The Yardbirds. Still sounding great today, Heart Full Of Soul and Over Under Sideways Down are included on Beckology along with other key tracks showcasing Beck’s creative use of fuzz box, feedback, distortion and sustain, the last exemplified by his solo on the Elmore James-inspired The Nazz Are Blue.

He later came to love the sound of the oud and was long interested in quarter tones. When he and composer Jed Leiber were asked to supply the score for an Australian TV series about photo-journalism in the Vietnam war, Beck immersed himself in the sounds, dynamics and intervallic details of Vietnamese music. The result, released in 1992 as Frankie’s House, is one of Beck’s most distilled, singular and searching achievements.

For all the eight Grammys he received, I suspect Beck might have treasured more the note of appreciation he received from Charles Mingus, thanking him for the version of Goodbye Pork Pie that Beck had cut on Wired. And when Beck was preparing Hot Rods And Rock And Roll – his 2016 “limited edition art book” of reminiscences and photographs – he didn’t ask one of his many colleagues and friends in the rock world to write the foreword. It was John McLaughlin who got the call.

Many years before, McLaughlin’s work on Miles Davis’s Jack Johnson had blown Beck away – as would his writing and playing in the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Shakti and various other cross-cultural projects. The two men jammed and toured together and in the mid-1990s, on McLaughlin’s The Promise, swopped contrasting yet complementary lines during their take on John Lewis’s Django. Their mutual respect and admiration stayed constant to the end.

Beck considered McLaughlin the outstanding guitarist of the contemporary world, calling him “the best there is”. He continued: “Supreme, on another plane entirely […] He has given us so many different facets of the guitar and introduced thousands of us to world music, by blending Indian music with jazz and classical.” McLaughlin was no less enthused by Beck, calling him “the greatest guitarist alive”. As he wrote in that foreword to Hot Rods And Rock And Roll, “Jeff is quite simply a ‘born’ guitarist. Not only does he have the mysterious talent that is innate, he has not stopped evolving over the years. He has forged a unique and wonderful style of playing that is instantly recognisable. He has the most fluid style of playing I’ve ever heard.”

Jeff Beck will be remembered, above all, for the soulful and searing sounds, underpinned and propelled by a rich range of rhythm, that he could coax – or demand – from a guitar (playing it, since the early 1980s, without a pick). But he should also be acknowledged, especially in his latter years, as a progressive bandleader who more and more chose to feature female musicians. Think of Tal Wilkenfeld, Jennifer Batten (elg) and Rhonda Smith (elb), for example, or the 2016 Loud Hailer with, a.o, Rosie Bones (v) and Carmen Vandenberg (elg).

And while some have reacted with less than glowing enthusiasm to 18 – his final album, cut with, a.o., Johnny Depp and with Beck contributing drums to some tracks – there’s enough of Beck’s sublime guitar sound and phrasing on, e.g., Midnight Walker, What’s Going On and Venus In Furs to underline what a sui generis spirit he remained to the end.

RIP, Mr Beck. You were truly something else.

Geoffrey Arnold (Jeff) Beck (24 June 1944 – 10 January 2023) is survived by his second wife Sandra Cash, to whom he had been married since 2005. There were no children.