Press photographer Geoff Ellis’s recollections of jazz in the West Country include lamenting the poor turnouts for Earl Hines and Willie “The Lion” Smith and watching idle punters toss bread rolls into the bell of a tuba. The connection between the two would probably not be lost on him. It’s all a world away.

When he joined the Bath Chronicle in 1957 on a trajectory that would include the Guardian, the Times and Now! magazine, his teenage love of jazz intensified. He was even persuaded to manage the Perdido Street Jazz Band, whose gigs included a Christmas dance at the Warminster Rabbit Fanciers Club. As well as being a Chronicle “snapper”, Geoff also became the paper’s jazz critic.

Bath and nearby Bristol were hothouses of jazz activity, almost exclusively the sort that Rex Harris had advocated in his book Jazz, published the year before by Penguin/Pelican and which became Geoff’s vade mecum in its espousal of the New Orleans tradition. It was “fundamentalist”; modern jazz, even in late 1950s and early 1960s Bath, was an incomprehensible peculiarity, notable in this book by its absence.

Despite these priorities, in 1964 Willie “The Lion” played to a pitifully small audience at The Regency, one of several jazz venues in the city. Organisers moved his piano on to the ballroom floor while the faithful few sat around it and enjoyed the great man’s music and reminiscences. A year later, Hines was at the Regency, supported by the Alex Welsh Band. After the gig but before he and the others had to depart for London at 1 am, Hines wished to know about Bath’s jazz scene; so Geoff, his wife Jean and two friends bundled him into a car for a visit to The Bell in Walcot Street, then the city’s leading jazz pub. Later they all ate omelette and chips at Biddy’s Café in Fountain Buildings. Hines memories ensued throughout. “Every joke was accompanied by massive roars of laughter and a large ‘piano’ hand clapping me on the shoulder,” Geoff recalls.

It’s difficult to underestimate the role “trad” jazz played at this time under pressure from Beatlemania and its tsunami effects. There were bands everywhere in Bath, among them the Milneburg, Riverside, Imperial, Perdido Street, Apex, Joe Brickell and Pearce Cadwallader, all playing at venues across the city and with interchangeable personnel. For a population of just 80,000, before the later influx of students to the new city universities, it was extraordinary.

The world-famous Bath Festival, a classical music event, grew a jazz limb in 1958, heralded in the streets by the Ken Colyer Original Omega Marching Band. Colyer’s smaller combo was a staple at the Regency, as was Chris Barber, Acker Bilk and the rest of the UK’s “trad” clan. Geoff had first come across Colyer’s New Orleans idol, George Lewis, at the Stoll Theatre in London. He later turned up in Bath. So did Buck Clayton, Nat Gonella, Henry “Red” Allen and Sister Rosetta Tharpe (at the Bath Pavilion), among many others. Over in Bristol at the Colston Hall, the musicians he saw and photographed included Duke Ellington, Kid Ory, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Bud Freeman and Ben Webster.

Geoff’s Lewis anecdote tells us a lot about the visiting old stagers from America. A couple of years after he first encountered Lewis in London, Geoff photographed and met him in Bristol in 1959 and Bath in 1966.

“He was a quiet, gentle and polite man and very self-effacing considering his jazz status,” Geoff says. “In Bath he was playing at the unlikely venue of the Percy Boys Club in Monmouth Place with the Barry ‘Kid’ Martyn Band.” Geoff and a musician friend went along before the show to do a few pictures. During the interval he ran back to the Chronicle darkroom and knocked out three prints, returning in time for the second set. At the end of the evening, George was given one of the pics. “He seemed truly touched that we’d gone to so much effort for him and he asked if he could autograph the prints for us,” Geoff says. “It’s a proud possession for both of us still.”

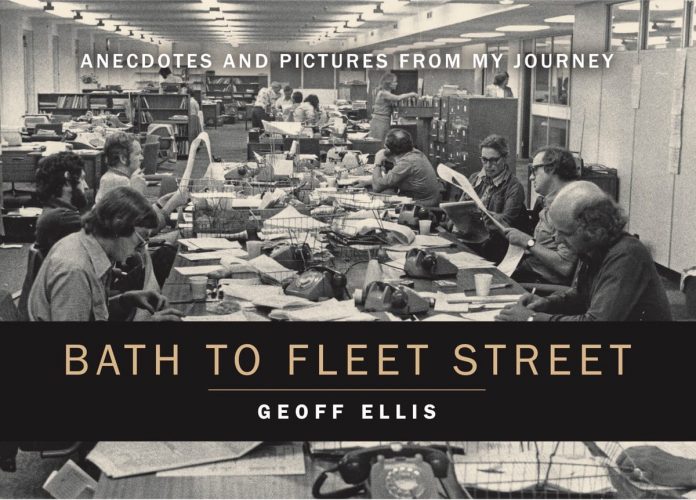

The jazz era remembered by Geoff Ellis takes its place in a book among others that have been superseded, especially by changing technology and not least the way images for reproduction in print are captured. Not a computer or a cellphone disturbs the creative chaos of the Guardian‘s sub-editors’ desk pictured at Farringdon Road in the late 1970s. Any jazz fan interested in news will warm to the book’s voluminous content and the skill with which people and incidents have been enshrined for posterity.

Oh – and about those tossed rolls. That was at the rabbit fanciers gig, where the Perdido band Geoff managed arrived in a borrowed van stinking of wet fish (the van and the band), and cider was drunk from jam jars. Those were the days. Interesting to think, however, that when the Milneburg band were playing at a Claverton Down gymkhana in 1961 – complete with banjoist – many lodestar jazz albums of the modern era had long been available.

Bath To Fleet Street by Geoff Ellis. Self-published: bathtofleetstreet.com. 264pp, pb, £18.50. ISBN: 978-1-8006815-1-4