Lazy types might well have filed Henry Cow under progressive rock long before now, but in this instance as in so many others that’s too convenient, for as Piekut’s borderline forensic account of the band’s existence shows, they always marched to a different drum, sometimes unconsciously, and emphasised the point with music that took in modern composition, art song, jazz and improvisation of various free shades. For that they maybe paid a price which went deeper than any exacted merely for dodging pigeonholes.

Piekut dwells on the musicological and the rigours of the road at the expense of the human, so only in passing do we learn of the dogged determination it must have taken for the band to actually work

Piekut’s attention to detail, while exemplary, dwells in the musicological and the rigours of the road at the expense of the human, so only in passing do we learn of the dogged determination it must have taken for the band to actually work and stay together over the course of its decade-long existence from 1968 to 1978. Much of the music it produced might be considered reflective of circumstances, but the fact remains that it stretched the rock form further than many of those who enjoyed higher profiles, and who conformed rather more easily to the progressive-rock label by dint of their reliance upon “received” virtuosity (and never being shy of applying it) and lyrical concerns which stretched from airbrushed mysticism to sword ’n’ sorcery clichés.

In the first three years of its existence the band played 46 gigs, with an average fee of £15 per gig. These figures, gleaned from drummer Chris Cutler’s booklet notes from one of the band’s 40th anniversary box sets, amounted to useful income for a band which was then still largely at Cambridge university, but of course amounted to less than enough to live on in grim reality, so in a sense the band’s decision to go professional even at that early point in its existence took courage. The ensuing years were ones of struggle, but as intimated above Piekut sidesteps that element, and while his engagement with what he calls the vernacular avant-garde and how the band are exemplars of it is thorough, his approach can occasionally feel reflective of the coldness of band intra-relations. He documents how when original bass player John Greaves left, he was the first member to meet his replacement Georgina Born, in a pub on London’s Portobello Road not far from the Virgin label office. Born found this significant because he proved to be the most affable member, as opposed to scary Chris or taciturn Fred (Frith, guitarist) for example.

The band was signed to Virgin, and while that arrangement raised its profile above and beyond what it might have achieved through diligent but spirit-sapping striving, the experience was also the impetus for the band walking right out of the music industry machinery and establishing a level of autonomy which the surviving ex-members have maintained to this day. Arguably because of Piekut’s understandable avoidance of the personal, to put it somewhat glibly, a lasting impression to be gleaned from the book is that the band’s very existence was a strong and deep-running spur, and the cult followings that band members enjoy to this day are primarily reflective of the fact that “difficult” music has and probably always will be the stuff of cults.

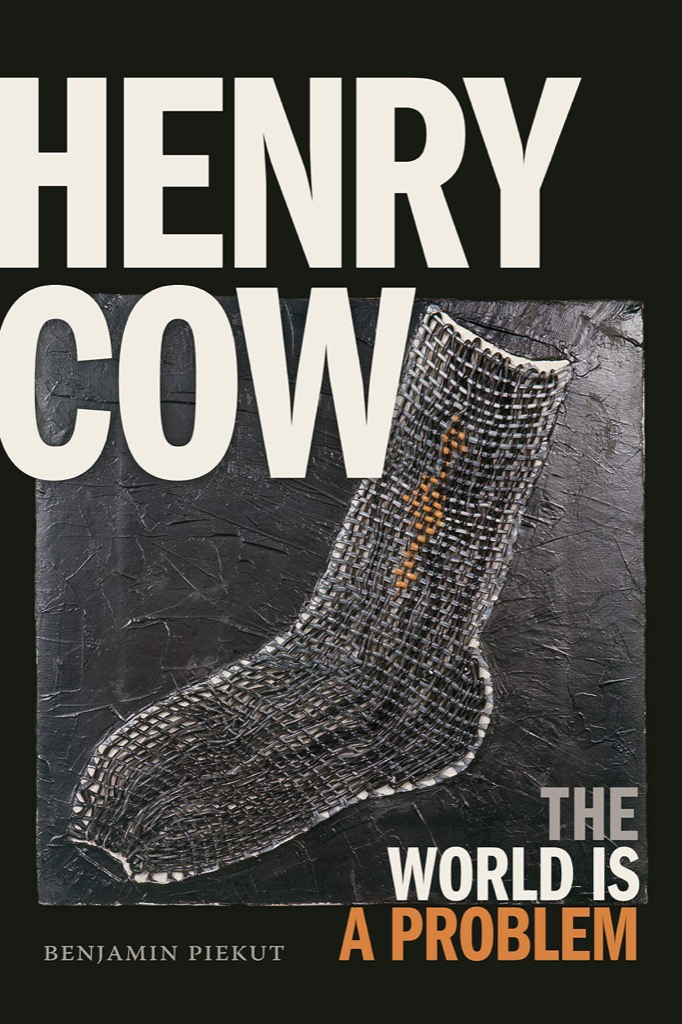

Henry Cow. The World Is A Problem by Benjamin Piekut. Duke University Press, pb, 407pp. ISBN 978-1-4780-0466-0