The problem is that Ginger Baker rather early disappeared behind “Ginger Baker”, the flame-haired irascible who notoriously broke the nose of a documentary maker who was attempting to record his life and passions. Jay Bulger’s Beware Of Mr Baker was an honest attempt to portray a complex and volatile artist, but the impression left – which was partly down to Bulger’s editing – was of a gimlet-eyed, carnaptious old rogue with a turbulent private life. None of this was strictly new. The long love-hate affair between Ginger and Cream colleague Jack Bruce, punctuated by fist fights, pulled knives, sabotage, endless bickering, was the stuff of rock legend, but again the emphasis always fell on the hate half of the equation. Jack admitted to a Scottish friend that he was “drawn” to the drummer, “like two planets orbiting each other, always at war, but somehow needing the other one to keep going”.

The further problem was that Baker’s entire career was defined by a (leaving out the 2003 and 2005 reunions) three-year association with two rock supergroups, the other one being the even shorter-lived Blind Faith. Ginger Baker’s recording career actually began in 1958 with the Storyville Jazz Men and Hugh Rainey Allstars and only ended in 2014 when he made Why? with Pee Wee Ellis, Alec Dankworth and Abass Dodoo. It was recognised that he had returned to his first and most lasting love when he formed a trio with Charlie Haden and Bill Frisell and then a group with the intriguing name Ginger Baker’s Jazz Confusion, but the jazz foundations of his work were constantly eclipsed by extra-musical concerns and by his association with heavy rock. Famously, Eric Clapton was not to be told that Cream was actually an improvising group.

Peter Edward Baker was born in Lewisham 19 August 1939, “just in time for ****ing Hitler and the ****ing Blitz”, he once said. His father – who rejoiced in the name Frederick Louvain Formidable Baker – was a brickie who fell in Greece when Peter was only four; his mother Ruby worked in a tobacconist, which may have been the source of the chain-smoking, sometimes overtaken by other addictions, that gradually undermined his health and may have contributed to his irascibility.

Cream was a strange mix, not just of personalities, but of musical styles, bringing together roots blues, psychedelia and heavily amplified jazz

He sometimes claimed to have opted for music just ahead of professional football. A former schoolfriend admitted that he was a “more than decent player”, but not West Ham or Spurs standard. He is sometimes described as a pupil of Phil Seamen, but Baker denied this, saying that he was entirely self-taught and that he only had a few collaborative sessions with Seamen, whom he admired and later employed with his Air Force group. Asked to name his influences – a question perilous for any journalist, given that Baker thought he was at the top of the pile – he often pointed to Baby Dodds, whom he admired for the lightness and clarity of his touch, but he also cited Art Blakey and Elvin Jones, more obvious in terms of intensity, and he admitted to a liking for Philly Joe Jones, with whom he at various times shared a heroin habit rather than a drumming style. His African work was in part influenced by Max Roach. One of his innovations, in rock terms at least, was the use of two bass drums, which he said he had borrowed from Ellington drummer Sam Woodyard.

Baker first crossed the path of Jack Bruce when they were members of the Graham Bond Organisation, but they may have met previously through Alexis Korner. Their feud began in Bond’s group, which Baker found confining and erratic, not least but ironically because of Bond’s drug addiction. One of Baker’s relatively few early compositions, Camels And Elephants, became the basis of Toad on Fresh Cream, an early example of the extended rock drum solo. Cream was a strange mix, not just of personalities, but of musical styles, bringing together roots blues, psychedelia and heavily amplified jazz. The group split up after four studio albums and a celebrated farewell concert at the Albert Hall.

Baker and Clapton briefly continued to work together with Steve Winwood and Ric Grech as Blind Faith, until Clapton drifted away and Baker took the reins as leader of Air Force. He had been an air cadet as a schoolboy and was, he said, “weirdly addicted” to the roundels that identified the RAF. The first Air Force album included Toad with solos by Baker, Seamen and Remi Kabaka, and a mixture of traditional material, African compositions and Harold McNair’s Da Da Man. Graham Bond was also back in the mix.

A meeting in London with Fela Kuti reinforced Baker’s interest in African music. He recorded with the Afrobeat pioneer, working uncredited alongside Tony Allen and then again on the underrated Why Black Man Dey Suffer, on which he claimed a cover credit. In 1974, he returned to heavy rock with the intermittently successful Baker-Gurvitz Army, co-writing a surprisingly tender tribute to the recently deceased Phil Seamen.

Having kicked a heroin habit by driving across the Sahara, Baker had a quieter time of it at the end of the 70s, making a couple more solo albums but mostly living in the backwash of supergroup identity crisis. He had set up a recording studio in Lagos, then still the Nigerian capital and the centre of the Afrobeat recording industry, but the business failed – an early example of Baker’s poor financial judgement – and he basically retired to Italy, living on a small olive farm, devoting very little time and attention to music.

In 1980, he recorded with Hawkwind and later with Public Image Ltd, adding to his Zelig-like status as a walk-on in almost every chapter of British rock. His willingness to stay the course in music was still uncertain. After moving to Los Angeles, he dabbled with acting for a while, but unsuccessfully. He also became obsessed with polo and moved to Colorado to put together a string of ponies. After a further dip into heavy rock with Masters of Reality, he relocated to South Africa; getting in and out of the US had become difficult due to his ongoing drug problems.

His set-up was unique, with his toms placed square to the floor rather than angled, and with a distinctive syncopation

From here on in, the picture is curiously forked, with Baker’s activities divided between surprisingly delicate jazz on the likes of Falling Off The Roof (1995) and Coward Of The County (1999), renewed involvement with African music, heavy rock with BBM (Gary Moore and, inevitably, Jack Bruce, at whose 50th birthday concerts he had played in 1993. Bruce said of this and of the equally inevitable Cream reunion: “It was good, but I was still relieved to know that we were living on different continents”. Trouble continued to stalk Baker. In South Africa, he was defrauded out of more than £25,000 by an assistant. Her defence was that they were lovers and the money was a gift. Baker didn’t think so. He was beginning to suffer from inflammatory arthritis and the cardiac problems that dominated his last years.

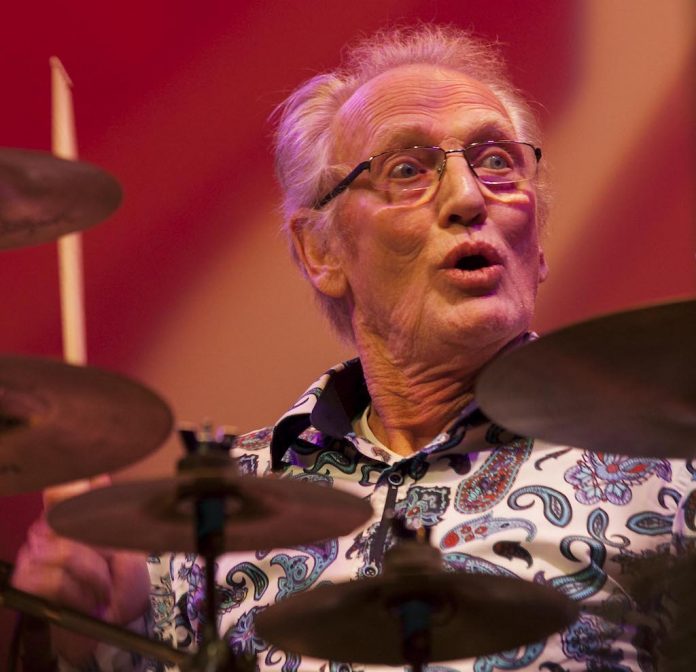

Baker is widely acknowledged as a major influence on rock drumming, though he disavowed some of the styles which claimed him. His set-up was unique, with his toms placed square to the floor rather than angled, and with a distinctive syncopation. Though his career began in the trad field, he was more obviously influenced by bebop. He’s not recorded as having said anything much about Roy Haynes, but he draws something of that fleet, highly musical delivery. For all his notoriety – which he stoked with an autobiography called Hellraiser – and association with hard rock, Baker could be a surprisingly delicate instrumentalist, often creating quiet melodic figures with clever use of hi-hat and bass combinations.

He married four times and was the father of three children, the youngest of whom was named after the Ghanaian drummer Kofi Ghanaba, who worked under the name of Guy Warren and was another significant influence on Baker. His heart problems increased after the making of Why? and earlier this year he was reported to be seriously ill, despite pioneering cardiac treatment.

Peter “Ginger” Baker died in Canterbury, 6 October 2019, outliving his best enemy by half a decade. In his own last weeks, Jack Bruce said of him, “Ginger, Ginger, Ginger, there’s only one of him, but you’re never sure which one you’re going to get”.