From his initial and life-enhancing discovery of jazz, poet Philip Larkin’s love of Louis Armstrong (1901-71) was expressed in broadcasts, correspondence, record and book reviews. As the first of his Desert Island Discs (14 July 1976), he selected Armstrong’s 1929 recording of Dallas Blues, and told presenter Roy Plomley:

“I suppose any jazz lover has to decide which Louis Armstrong record he’s taking, because there are so many and Louis is such a combined Chaucer and Shakespeare of jazz. I’ve chosen Dallas Blues because I’ve been playing it for about 40 years and never get tired of it. It is a blues, and Armstrong plays it in a beautiful and relaxed way that he doesn’t achieve on his later more showmanship dates”.

Nearly 40 years earlier, writing to fellow jazz enthusiast, Jim Sutton, Larkin had warmly commended this performance. Armstrong’s trumpet break served “the double purpose of drawing attention of the listener to the soloist” and allowed the saxophonist “to change from clarinet to saxophone in roughly three and a half seconds, leading up to the perfect last chorus on trumpet (Blues playing personified)”.

Larkin later told Sutton that he’d been listening to Armstrong’s 1927 version of Savoy Blues, and although the “early Armstrong” was less impressive than “Golden Age Armstrong”, he sometimes got very close. On Savoy Blues, Armstrong played “2 of his most restrained and delicate choruses. Bix was an incompetent blaster compared to Louis! For me the biggest thrill is to imagine what the other players felt like. Did they feel they were making jazz with a genius? I wonder”.

…the young Louis ‘had grown up to hear all the components of jazz melting into each other and by bringing them into the focus of his own definitive style, had created the jazz language’

In a 1965 article entitled Requiem For Jazz, Larkin reflected on Armstrong’s significance and stature. He had been “the great integrator”. Born in the musical and cultural salad bowl of New Orleans in 1901, the young Louis “had grown up to hear all the components of jazz melting into each other and by bringing them into the focus of his own definitive style, had created the jazz language”. It was then that “he gave jazz its speaking voice and it was heard all over the world”. It had certainly been heard by an adolescent jazz fan in Coventry:

I was born the day after Louis received that telegram from King Oliver summoning him to Chicago, and as soon as I was old enough to wind up a gramophone I was sold on his music. West End Blues, Dallas Blues, St. Louis Blues, all of them took hold of my mind like poems, or better than poems, for you were taught those in school, and I had found this wonderful music for myself.

A conflation and summary of his writings on Armstrong reveals that Larkin (pictured left, courtesy University of Hull) considered him as the greatest jazz trumpeter and vocalist, a remarkable human being, an African American who overcame daunting odds, and ultimately, as a key figure in the pantheon of 20th-century artists. Not least – and unlike his other heroes – King Oliver, Sidney Bechet and Duke Ellington – Armstrong, in some respects, actually improved with age. In All What Jazz, there are 20 reviews of Armstrong recordings, in which Larkin refines and amplifies his estimates of a “central talent into which flowed the many tributaries of jazz; his innovation was a throbbing, personal tone which demanded to be heard alone instead of as part of an ensemble”. The Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings provide evidence “of Armstrong’s enormous talent bursting out of its chrysalis”. More remarkable things were to come. It was his 1929 recording of St. Louis Blues that Larkin dubbed “The Hottest Record Ever Made”:

Starting in medias res, with eight bars of the lolloping tangana release, it soon resolves into a genial uptempo polyphony. Armstrong shouts a couple of blues choruses not to be found in the original Handy song sheet, then after 12 bars of Higgie’s trombone Louis leads the ensemble in four blistering choruses of solid riffing. By the third chorus the whole building seems to be moving.

An anthology of Armstrong recordings from the 1930s – Louis In Los Angeles – featured 16-year old Lionel Hampton on such titles as Ding Dong Daddy, Body And Soul, Dear Old Southland, Mahogany Hall Stomp and Ain’t Misbehavin’. Armstrong was not the star soloist, “but his good-humoured virtuosity is so compelling that the ear capitulates”.

Reviewing Satchmo At Symphony Hall (Boston, 1947), he lamented: ‘We accept mugging, set solos, mediocre support, short-winded trumpet and long-winded vocals with tears in our eyes’

However, Larkin had mixed feelings about the several 1940s and 50s “live” recordings by Armstrong and his (varying) “All Stars”. Reviewing Satchmo At Symphony Hall (Boston, 1947), he lamented: “We accept mugging, set solos, mediocre support, short-winded trumpet and long-winded vocals with tears in our eyes”.

He also cursorily dismissed the celebrated New York Town Hall Concert (1947) with the tart observation: “Some of the Town Hall trumpet is so good it must be Bobby Hackett”. He was not always right. Armstrong’s lead trumpet playing (and his vocal duets with Jack Teagarden) matched anything in his post-war career.

A 1955 concert, recorded in Los Angeles, Louis Armstrong At The Crescendo, prompted Larkin to reflect: “How shocked we were that the All-Stars were not a conscious resurrection of the Hot Five”. Yet despite numbing bass and drum solos, and the dire vocals of Velma Middleton, a few tracks – St Louis Blues, Someday Sweetheart and Back O’Town Blues – reflected “Louis’s mixture of righteous jazz and vaudeville entertainment”.

He also had doubts about the reissue of the Armstrong/Ellington collaboration [The Great Reunion] where “Louis’s blow-torch vocals dominate Duke’s rather bored-sounding piano”, and concluded: “Let’s face it, the two men have almost nothing in common, but Solitude and I Got It Bad showcase Louis’s murderous ability to hit a tune on the nose”.

Curiously, Larkin didn’t rate as highly as most critics the 1954 studio album (produced by George Avakian) Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy. Reviewing its reissue in 1969, he judged the session to be “classic” yet “not perfection”, but conceded that some tracks and in particular Chantez-les-Bas and Yellow Dog Blues, – were superlative. “The moment in the former, when Armstrong starts to sing ‘Just ‘fore day’ is unforgettable”.

Of Moon River: ‘I came to the conclusion that it is Armstrong’s staggering and economical sincerity that makes this kind of number succeed. It brought tears to my eyes. What it does to teenagers I hardly dare hope’

Larkin welcomed Armstrong’s predominantly vocal recordings of the 1950s, 60s and 70s. These included Louis And The Good Book, a collection of spirituals with an affecting performance of Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child”, and Country ‘n’ Western Armstrong – “an excellent idea gone a little wrong” but “some of the tracks had me hollering”. The LP Hello Dolly gave him particular pleasure:

To hear Louis’s colossal voice tearing up words by the roots (‘mel-o-dee’) is still an awesome experience. Listening to his Moon River, a piece of slop if ever there was one, I came to the conclusion that it is Armstrong’s staggering and economical sincerity that makes this kind of number succeed. It brought tears to my eyes. What it does to teenagers I hardly dare hope.

He was even more commendatory of Louis as vocalist in a review of a double LP set, The Singing Style Of Louis Armstrong, recorded with the Oscar Peterson Trio and the Russell Garcia Orchestra in 1957:

What astonishes is the ease with which this man, pushing 60, creates twenty-two valid jazz experiences simply by singing that number of well-known commercial songs without recourse to excessive mugging or bravura, just a slur here, an emphasis there, the use of the varying textures of his amazing voice. I listened to all twenty-two tracks at one sitting and didn’t dismiss a single one as a dud.

Louis Armstrong And His Friends (1970) was his penultimate studio session. Produced by Bob Thiele and arranged by Oliver Nelson with a choir and strings, it was attended by such “friends” as Eddie Condon, Ruby Braff, Ornette Coleman and Miles Davis. An ailing Louis, too ill to play his trumpet, was still able to sing. Larkin was intrigued:

What is interesting here is the change of repertoire. The pièce de résistance (in more senses than one) is [the civil rights anthem] We Shall Overcome. And it isn’t unimpressive in a Cup-Final kind of way, everyone joining in and giving an impression of overwhelming solidarity, but coupled with [John] Lennon’s Give Peace A Chance, doesn’t this suggest that now Joe Glaser [Armstrong’s longstanding manager] is dead, Louis is being wheeled into the radical ranks?

Shortly after Armstrong’s death – “the great oak uprooted at last” – Larkin received a letter from his editor at Faber & Faber, suggesting that a new biography of Armstrong would be a good idea, and hinting that he might be the man for the job. Larkin declined the veiled invitation, but made clear his considered estimate of Louis:

It is already accepted – or if it isn’t, it soon will be – that Louis Armstrong was an enormously important cultural figure in our century, more important than Picasso in my opinion, but certainly quite comparable, and this being so there are bound to be a good many books and articles written about him as time goes on.

In an elegiac tribute published in 1971, Larkin reprised some of the sentiments he had already expressed regarding Armstrong’s legacy and significance.

We had given him our allegiance in the teeth of our elders’ contempt. ‘Jungle music…and why doesn’t he clear his throat?’ Now we were shown to be right. Armstrong was an artist of world stature, an American Negro slum child who spoke to the heart of Greenlander and Japanese alike. At the same time, he was a humble, hard-working man who night after night set out to do no more than ‘please the people’, to earn his fee, to pay back his audience for coming.

In another eulogy, intended for BBC Radio 4 (but not broadcast), he stressed Armstrong’s importance and universality:

More than anyone, it was Louis Armstrong who, from the operas and spirituals and marches that hummed around his head in New Orleans in the nineteen-hundreds, forged the style of modern popular music, the songs we sing, the rhythms we dance to in the narrower world of jazz, a whole era, if not the music itself, comes to an end with him.

Significantly, he again chose to recount the hardships and tensions of Armstrong’s exemplary life:

He was born an American Negro in a New Orleans slum. He had no education but what he received in the Coloured Waifs Home. He was an artist, but his art wasn’t recognised: he had to create its acceptance, giving two shows a night and then going on by bus or plane, blowing when his lip was shot, never taking a holiday. During the royal progression of his post-war tours, he had to rely more and more on his voice to carry the show – but what a thrilling, what a human singer he was!

Armstrong had been “a great artist of our time”, and his musical legacy “will be our joy for years to come”. He had “lived his life, full three-score years and ten, and he spent them entertaining us”.

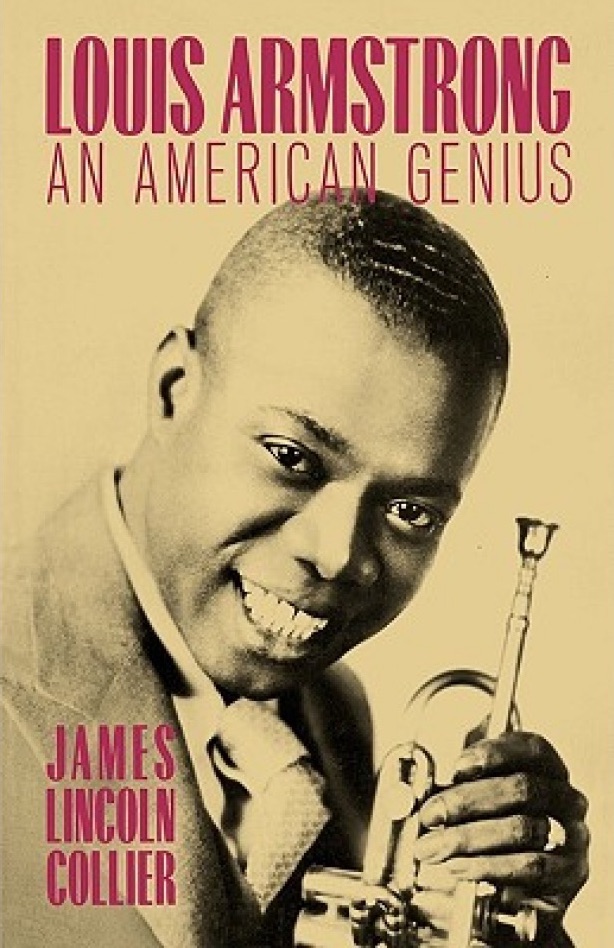

Larkin’s final evaluation of Armstrong appeared in his 1984 review of James Lincoln Collier’s unduly harsh portrait Louis Armstrong: An American Genius. Dismissing his assertion: “I cannot think of another American artist who so failed his own talent”, Larkin counters with “one could do without any twentieth-century artist sooner than Louis Armstrong”.

James Lincoln Collier: ‘[Armstrong] became subservient to a “succession of ruthless managers who treated him like a performing animal”’

Collier, a confirmed Hot Five devotee, had castigated Louis for subsequently electing to follow “a career of stage mugging and eye-rolling vocals”. Armstrong, he argued, had “never escaped the limitations of having been born into the depressed and deprived African-American working class of the Deep South” and then became subservient to a “succession of ruthless managers who treated him like a performing animal”.

Larkin considered these judgements profoundly wrong-headed and depressing and asked: “What does Collier expect Armstrong to have done about it? Turn himself into Miles Davis? Put the Negro question forward 50 years?” Louis, he concluded, “was something more than an end-product of compulsions and compromises – a great artist, a great personality, and a great human being”. As Richard Palmer observed: “These two rhetorical questions express more than impatience; there is genuine anger here. Collier’s book really upset Larkin, and the demolition of the book’s inconsistency and tone has an unusual savagery beneath the characteristic suavity”.

From the mid-1950s, Louis made several visits to the UK. Jean Hartley, Larkin’s friend and second publisher, remembered going with him and friends to an Armstrong concert at the Spa Royal Hotel in Bridlington in April or May 1962. After impatiently sitting through the supporting acts, they finally saw (and heard) a living legend accompanied by Trummy Young (trombone), Joe Darensbourg (clarinet), Billy Kyle (piano), Billy Cronk (bass), and Danny Barcelona (drums), with the undistinguished Jewel Brown as vocalist. She recalled:

We feared that Armstrong would be inaudible but the first notes he blew, as the group walked on, assured us that their decibel level was entirely adequate. We were seeing a great trumpeter, past his prime, rather stagily using his handkerchief to mop his brow and, understandably, not busting a gut for his hick audience. Nevertheless, I was moved to tears a couple of times: once during Blueberry Hill and again when he sang a superb, slow-tempo version of A Kiss To Build A Dream On.

Larkin later wrote:

In the first half of the concert of his that I ever attended, the British group huddled round the microphone as if they were trying to light cigarettes at it. When Armstrong came on he stood twenty feet back: his trumpet filled the hall. I thought of that worried recording company engineer in Richmond, Indiana, in 1923, shifting Louis farther and farther from his primitive equipment.

Writing to his mother, Larkin recounted his trip to Bridlington “to hear a Louis Armstrong concert” and confessed “this was a very great thrill for me, as Armstrong is the Shakespeare of jazz even now, & I’ve never seen him before. You’ll see a picture of him in the Sunday Times today”. (26 April 1962).

After spending a convivial evening with Larkin in Hull in 1982, writer and sailor Jonathan Raban said that depending on the weather, the next port of call on his voyage around the British Isles in his thirty-foot ketch would probably be Bridlington. This nautical intelligence elicited from Larkin the reflection “Bridlington. Ah, Bridlington. You know I once heard Louis Armstrong play in Bridlington”.

Sources

Anthony Thwaite, editor, Philip Larkin, Further Requirements: Interviews, Broadcasts, Statements and Book Reviews (2001); Selected Letters of Philip Larkin 1940-1985 (1992).

Philip Larkin, All What Jazz: A Record Diary 1961-1971 (1970, 1985).

Richard Palmer & John White, editors, Larkin: Jazz Writings and Reviews 1940-1984 (2004).

Jean Hartley, Philip Larkin, the Marvell Press and Me (1989).

James Booth, Philip Larkin: Letters Home 1936-1977 (2018).