This is one of a series of taped interviews with musicians who are asked to give a snap opinion on a set of records played to them. Although no previous information is given as to what they are going to hear, they are. during the actual playing, handed the appropriate record sleeve. Thus in no way is their judgment influenced by being unaware of what they are hearing. As far as possible the records played to them are currently available items procurable from any record shop.

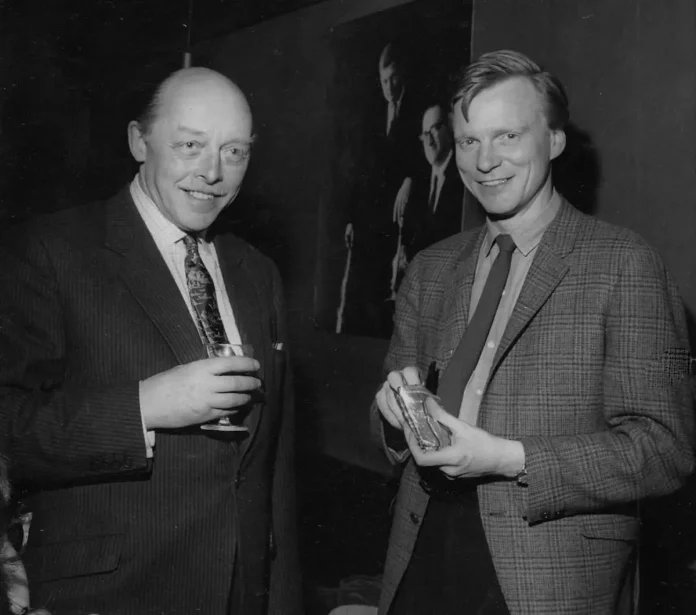

One of the leading exponents of the baritone saxophone, Gerald Joseph Mulligan also plays the piano, and is an arranger of considerable note. He first came to prominence through his writing for the Miles Davis nine-piece band that played the Royal Roost in 1948. The provocative and unusual scores for such titles as Jeru, Godchild and Venus De Milo took the jazz world somewhat by surprise and were then considered daring and different. Since those days Gerry has led various small groups often in company with his old friend and partner Bob Brookmeyer. A humorist, both off and on stage, Mulligan shows a keen insight into the jazz world today. – Sinclair Traill

Monk’s Mood. Thelonious Monk – Thelonious Himself. Riverside RLP 12-235

Well, you either like Monk, or you dislike him – I have always liked him. He deals out a steady stream of ideas that are all easily recognisable and can become tiresome if listened to too much. His approach to things is usually very refreshing; he has his own individualistic approach to a song or ballad which can be most unusual. This kind of rambling thing here, still had a kind of form to it that wanders and wanders, yet one can still anticipate where he is going to go. He likes to experiment with percussive effects with the piano. When I made that record with him I did it on the one condition that we did ’Round Midnight, but when we came to do it he wouldn’t play it as the kind of romantic thing I wanted it to be. It is a lovely tune and I am an incurable romanticist. Monk tried to angularise this lovely tune, and he would not let me play it as I wanted to – but I gather the record sold well, so perhaps Monk was right after all.

Villes Ville. Duke Ellington – Blues In Orbit. Philips BBL 7381

What is there left to say about Duke? He’s just wonderful! Particularly now and for the past year or so when he has had a really great band. The return of Lawrence Brown and Cootie Williams seemed to do something to the rest of the band – a kind of shot in the arm. The band now really sound like its old self. I wish Carney and I had more chance to play that thing Duke wrote for two baritones. We did it twice, once at Newport and the other time at a concert at Lewisholm Stadium. I would liked to have done it many more times. What a title Duke gave it! Prima Bara Dubla. Doesn’t he think up some titles? The one you just played made me laugh, Villes Ville Is The Place, Man! What a thing to call a tune; yet somehow it seems right. Incidentally I should have said how much I love Carney’s playing – I’d like to record that tune again sometime. It could be even better.

In A Little Spanish Town. Bobby Hackett. Capitol T 857

Great fun. I was sorry I missed that band, for I heard a whole lot about them and that instrumentation. I know Bobby well and of course Dick Cary, who no doubt did those arrangements. Who was that crazy tuba player? John Dengler. I have never heard of him, but he certainly can play that thing. I would like to have heard some of the other tracks on that record; some other track that wasn’t a parody like that was – good, but a kind of musical joke. It is fine to hear Bobby playing open like that. The last few times I’ve heard him he was at the ‘Embers’ where he had to play into one of those buckets all the time – mustn’t play too loud or you’ll drown the customers eating noises.

But that tuba – what is the future of the tuba as a jazz instrument? Playing solos like that is I suppose just a novelty. I’ll never forget when we had that little nine-piece band with Miles. Phil Barbour, who played tuba with the group, I am sure wanted to play solos – he was fantastic, he used to transcribe Lester Young choruses and play them when nobody was looking. It’s such an unwieldy instrument that although one can use it, and indeed in some cases needs it to fill in a jazz ensemble, the instrument is not a jazz instrument in a strict sense.

I think, by the fly way Dengler plays on this record that was an Eb tuba, not the monster kind that Johnny Dankworth uses. I think Dankworth’s tuba is a mistake, for having no baritone to balance the ensemble sound of the band, that wretched tuba is just left standing there in the bottom all by itself. It kind of unbalances the band to my ear.

When I scored those parts for Miles, we had one simple idea in mind. Starting with the lowest note we could (a baritone only goes down to Db) we tried to have a continuous chromatic scale that went up as far as it would go. We didn’t really explore it above the trumpet, we could have by using a clarinet or flute, but we left it with the trumpet. The thing we were trying for was to start at the bottom and to have a continuous, overlapping sound so that you were not conscious of a change in sound as we changed instruments. Which is one of the biggest flaws in the danceband setup. You have three trumpets, three trombones, and four or five saxophones, and the sounds don’t really meet and overlap. You can’t have a passage by the trumpets changing over to the trombones or saxes without a big change in the quality of the sound.

So we were trying for a kind of continuity of sound, and I think with the tuba, the French horn and baritone, those three horns together made enough of a similar sound, so that by writing in unisons and overlapping and then dropping in and out of the unisons, we could start right at the bottom and go right up without any break in the quality of sound. Anyway that was the idea. It was almost like working with a keyboard.

Tragedy. Don Ellis – New Ideas. Esquire 32-183

Of course there is always the problem of what is jazz and what isn’t? What interpretations can the music take? Personally I am inclined to stick with things that are traditionally more in the jazz mould. I know that some of us who came along in the middle and late forties, we also had resistance to what we classified as jazz because we were then playing something that was in some ways different to what had gone before. The sides with Miles were, by some, classified as being a long way out, but in retrospect now that seems so silly, for what we were doing was much ‘further in’ than many of the critics realised.

But this whole thing: In looking over Don Ellis’s notes on it, I see he was inspired by John Cage and that he is interested in certain aspects of music that I can’t take seriously anyway. As composers’ exercises and fun and games it is one thing, but as serious music I don’t think it qualifies. The techniques they are evolving can be of use, in say film writing for a set of pre-named tone-clusters, so you have some control over the atonal music. Of course the John Cage business deals with plot-time rather than rhythm-time. The kind of thing they do is to play such-and-such for a minute, timed by stop watches.

Jimmy Giuffre played around with this form for a time, but of course his music was rooted more deeply in traditional jazz concepts. That always comes out in what he does – for instance I always know he is from Texas. His sound and whole rhythmic approach are right from Texas. Geographical compartments in jazz may not mean much, but you can always tell a guy from Texas! I know a lot of guys from there and they all have some kind of similar quality in their playing. It doesn’t matter what instrument they play, they all have that certain quality – and Giuffre has it strongly.

From the Texans you can exclude Jack Teagarden from that statement, because he is such a polished player who plays with such delicacy, even when he is what I call ‘twanging’; and you know he does have a real drawl in his playing. There is a strange combination in his playing, the drawl or ‘twanging’ as I call it, and an utmost precision. He uses few of the vocal effects that one can do with a trombone, but he is the most precise trombonist I have ever heard.

Thunderbird. Willis Jackson. Esquire 32-182

That’s good to hear, I don’t get too much chance to listen to many of the stomping groups these days. Of course I don’t really listen to much that goes on today; I’m not that much interested in what the rest of the people are doing. When I’m involved with my own things I’m not too concerned with what’s going on, especially as much of what is happening now doesn’t interest me too much. Frankly there is not too much I hear these days that I like too much. When I first started to play I listened a lot – there were a lot of people I liked then, such as Charlie Parker. Of course, I listen to Duke all the time, and back in the forties there were a lot of talented arrangers and a lot of good bands. Jazz must be a means of expression; if one feels like Willis Jackson, then play like that; if one feels like Don Ellis, then play like that – it’s an expression for individuals.

Partatela. Woody Herman’s Fourth Herd. Jazzland JLP 17

Well, any record that has Zoot Sims on it can’t be all bad! When Zoot starts to play I always start smiling – he always makes me happy. He’s a real spark plug! What a tragedy it was that Eddie Costa was killed just as he was coming to his peak – he was one of the most exciting piano players I have heard in years. Al Cohn, in the things he wrote for this band, liked to go real way back to the thirties for a device, but the treatment would remain his own. Woody led some great bands, but none better than this one.