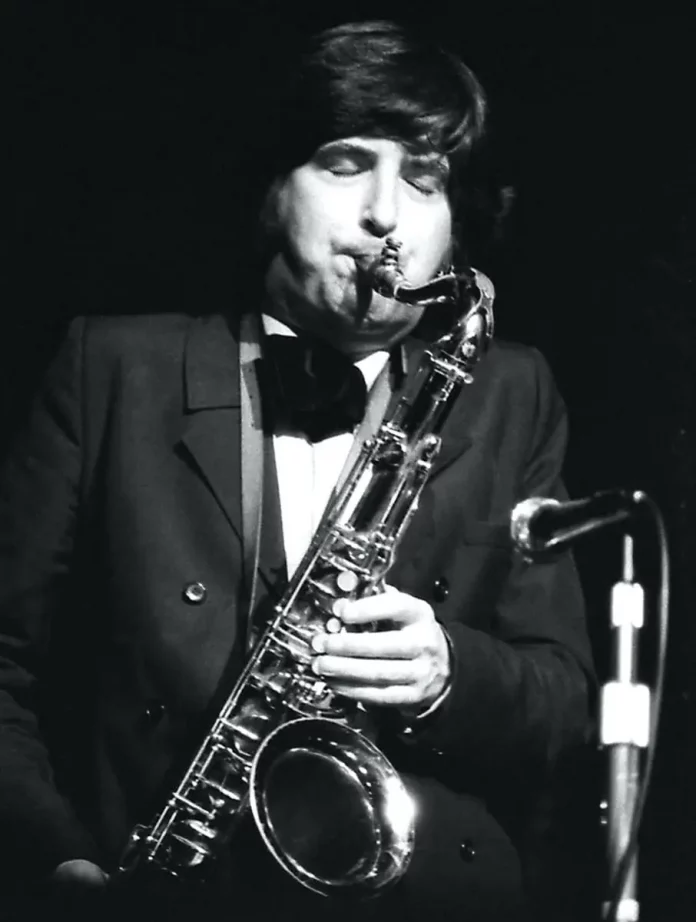

THE TEST: TONY COE

Anthony George Coe was born in Canterbury in 1934 and began playing the clarinet around 1948. He had classical training on the instrument from Paddy Purcell (a pupil of Charles Draper) and took harmony lessons from Donald Leggatt, director of music at St Edmunds School. His interest in jazz was sparked by his father’s Ellington collection and the sound of Benny Goodman, and he acquired early musical “muscle” through regular work with a Canterbury dance band. Later he studied composition, including serial music, with Alfred Nieman and acquired a particular taste for Alban Berg. This mixed upbringing led to a career of contrasting musical involvements, including mainstream jazz with Humphrey Lyttelton, film scores with Henry Mancini, ancient and modern classical music with Alan Hacker’s Matrix and free improvisation with Derek Bailey.

Tony Coe was tested by MARK GILBERT (the article reproduced here from Jazz Review, April 2004)

JOHNNY DODDS

Blue Clarinet Stomp, from Blue Clarinet Stomp (1928)

Dodds (cl); Charlie Alexander (p); Bill Johnson (b).

BLUEBIRD ND 82293

That’s some vibrato, isn’t it?

It’s Dodds, isn’t it?

Yes – no catches there – do you know the piece?

No. I used to play in a trad band in Canterbury but I got the sack for being too modern. It was based on this kind of period.

Did you study this period much?

No. I didn’t. I mean, I really came in with Goodman. Goodman was the first influence, and, of course, my father used to play Ellington things.

With Bigard in, and so on?

Oh Bigard, yes. I’ve always loved Bigard’s playing. I was very pleased to play with him at Nice, way back. We were about four or five clarinets – there was Bigard, Daniels, Wilber, Davern and myself. It’s actually on video. But that’s nothing to do with this. This music has a special charm – it’s very vocalised.

When did you start learning clarinet?

About 1947, 1948.

So Goodman would have been one of the clarinet men of the day?

Yes – I mean that was pop music in those days. Funnily enough we were just listening to “After You’ve Gone”, and that was a hit, you know.

And I loved Artie Shaw. I sort of became these people. I used to play in a dance band around the corner six nights a week in Canterbury and it was wonderful really. You had to wear a tuxedo and I became Artie Shaw and I became Goodman for a bit. Then I became some clarinet player I’d seen in a film. I was very happy, actually, because to be able to earn a living playing round the corner was great. We had to play everything, of course, and that was good. See, that’s what’s lacking these days – it’s dance band experience. It gave you muscle. But these days they have jazz courses and they just sort of do that. Which is fair enough, but I’m not really in favour of blackboard teaching of jazz at all. And the reliance on scales and all that has to be treated with caution. One should be aware of it, and Bird and Dizzy obviously were aware of scales, but it was more intuitive with them. These days the reliance on scales has become too important. There’s not enough playing by ear, perhaps.

I think earlier players were used to playing more thematically, off the melody.

Well, they knew harmony a lot.

They played a lot of arpeggios.

Well, Goodman played arpeggios, and so does Dodds, come to that.

With linking material… It’s interesting that in the classical field the opposite principle applies – scales and other technical work are the prelude to real playing.

Well, not many non-jazz players improvise, do they? People like Mozart used to be more than just composers – he could improvise, conduct, play instruments to a high level. These days you have people that are just good at one thing. I think it’s a pity there’s not a broader musical education.

The jazz scene, at any rate, has changed – with recorded music and synthesized music there isn’t the requirement in popular music for live players, and so fewer opportunities for the old kind of musical apprenticeship. You can wonder where today’s jazz students will work.

Yeah. Well, John Taylor, when we were teaching at Wavendon, said, “We’re educating our future audience”. Rather a sad thought, really.

Having said all that, the instrumental standard among young players is so high now.

Oh yeah – we’re into the age of the educated jazz musician.

Did you have formal tuition?

Oh yes – I had formal tuition on the clarinet. I was a pupil of Paddy Purcell, who was a pupil of Charles Draper, one of the great English clarinet players. Paddy Purcell’s grandson is Simon Purcell, by the way – the jazz pianist. And I had my first harmony lessons from Donald Leggatt, musical director at St Edmunds school in Canterbury. I didn’t go there, but I used to play in the orchestra. And later on I did study composition with a lot of people.

(As Dodds continues)

See, Dodds didn’t play a Boehm system. He played a simple system or something like it, and you definitely get a different sound, better really. Also, Barney Bigard didn’t play a Boehm system, nor did Fazola. I’m forever trying to get that sound on a Boehm and I’ve been partly successful. There’s a purity in the timbre. It’s more the true clarinet sound, really. Alan Hacker would explain it perfectly, because he is Mr Clarinet. He’s a great influence, incidentally. I wouldn’t be the same if we hadn’t met.

DUKE ELLINGTON

Rockin’ In Rhythm, from The Definitive Duke Ellington (1931)

Freddie Jenkins, Arthur Whetsol, Cootie Williams (t); Lawrence Brown, Joe “Tricky Sam” Nanton (tb); Juan Tizol (vtb); Barney Bigard (cl, tb); Johnny Hodges (as); Harry Carney (cl, bs); Fred Guy (bj); Wellman Braud (b); Sonny Greer (d).

COLUMBIA/LEGACY 501034 2

I’m not terribly good on the personnel of the early Ellington band. Johnny Hodges probably wasn’t on the lead alto – it was probably Hardwick or something like that.

It is Hodges.

Hodges did change his sound, from a sort of schmaltzy sound to a more incisive sound. He did spoil me for most other lead altos. It was penetrating and a big sound at the same time. Somebody on the clarinet now – who is it, though? It’s not Bigard, is it?

There are two clarinets in the band – Bigard and Carney – and I think it’s Bigard who solos here.

Could be Bigard, because it’s early and he hadn’t matured fully. Who’s the trumpet now? Is it too early for Tricky Sam? Whatever, I love it. It’s wonderful.

Was there anything you took particularly from Bigard?

Yes – I love the way he kind of floated, and I love his legato. It’s a beautiful legato and a beautiful sound. When I was with Humph, I went for a Bigard type of approach, which you can hear on some of the old recordings. It’s sort of a limpid style – I love the way he plays. I love Ellington – it was some of the first jazz I heard, really. My father had these 78s.

Did you ever hear the Weather Report version of this tune? The piano intro seems to be at a similar pace but then it launches into a much brighter tempo.

No. It would be good though, wouldn’t it?

COUNT BASIE

(The) Fool On The Hill, from Basie On The Beatles (1969)

Gene Goe, Sonny Cohn, Luis Gasca, Waymon Reed (t); Grover Mitchell, Melvin Wanzo, Frank Hooks (tb); Bill Hughes (btb); Marshal Royal (as, cl); Bobby Plater (as, f); Eric Dixon, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis (ts); Charlie Fowlkes (bs); Basie (p); Freddie Green (g); Norman Keenan (b); Harald Jones (d).

OCIUM OCM 0022

It’s a Beatles tune. It’s Basie.

How did you spot that?

The lead alto sound, but also the precision. You know I nearly joined him?

Yes – why didn’t it happen?

It was nice to be asked, but I’m glad it didn’t come off in a way because I wouldn’t have enjoyed travelling all over the world in a big band, to tell the truth. I would have lasted about a fortnight. It didn’t work out because for some reason Basie himself took over the job of fixing it all, all the bureaucratic side of things, but he didn’t do it very well. I would have taken Jaws’ place, which would have been quite a seat to fill especially the way I was then.

(As the flute solos)

There’s something about jazz flute in those days. There are more people playing jazz on the flute now, and they can actually play the flute better. I’m not being completely derisive about this, but doubling is not such a good thing. If you’re playing two saxophones and a flute, you’re not going to get the best results on the flute, are you?

What do you think of Eric Dolphy’s flute playing?

Well, I haven’t really thought about it, you know. I’m not actually an Eric Dolphy fan, to tell you the truth, no. I find it chancey. He was trying to do something, but he didn’t actually accommodate the harmony a lot of the time. There’s too many wrong notes, and I mean “wrong”. They say there are no wrong notes in jazz – well, there are.

He certainly always seemed to be winging it, on the edge of being there, which is perhaps what appeals to his admirers. Maybe that’s a quality in itself – that he doesn’t always get there.

Well, sorry – I’d rather hear somebody who gets there. I don’t see any point in murdering nice tunes. I don’t think there’s any point in it at all. It’s sort of Dada-come-lately. Sort of destroying things for the sake of it. I suppose the movement had to happen.

Do you include Ornette Coleman in that?

I haven’t heard him lately.

Coltrane?

Coltrane, no. I think he’s a master, you know.

But Ornette from the late 50s?

No – I haven’t heard it, sorry. Were you gonna play one? You know, my listening is quite eclectic, in a way. I can’t say that most of the things I listen to are jazz at all. A lot of it is European music, what you might call classical. And I love vintage bands too, especially the old English ones, Al Bowlly and all that. And I love Fred Astaire. I’m not alone, ’cause Ruby Braff loved all that stuff as well.

That’s interesting, because you’ve also played a good deal of avant-garde music too.

Yes, sure – I did some things with Derek Bailey.

A lot of chance going on there.

I know. But I must say I wouldn’t pay to go and see avant-garde. It’s very chancey, especially if you’ve got more than two people playing. The more people you have, the riskier it is, and the harder it becomes to finish. You think it’s over and then some idiot starts up again. I find it’s really boring. Boulez said he couldn’t stand more than two bars of improvised music and I can sort of see what he means. There are exceptions – I love what Evan Parker does. He plays solo most of the time, and that’s fine, because he’s in control and doesn’t have to cope with the harmonic mud that happens a lot with improvising groups. I think he’s very inventive. I just love his things, on the soprano and tenor.

It’s not obviously melodic.

You mean tunes you can whistle? You could whistle them if you were good enough. I love all of it – his choice of notes, the sound. His approach is phenomenal – it’s a special technique he has. Pity you weren’t gonna play one of him.

THE BEATLES

Lady Madonna, from The Beatles/1967-1970 (1968)

John Lennon (g, v); George Harrison (g, v); Paul McCartney (b, v); Ringo Starr (d) plus others unknown.

EMI 0777 7 97039 2 0

Here’s the key bit – the sax player. Do you know who it is?

Is it a sax or a kazoo? Sorry. Or maybe it’s the sound engineers made him sound like one.

Pretty tinny production, isn’t it?

Yes – he probably had no choice. He was probably ordered. He might be a very good sax player for all I know.

It’s been suggested it’s Tony Coe.

It might be, but I know I don’t play with a sound like that, so they must have done something to it.

You don’t recall playing on this session?

I don’t know who it is – the group, I mean.

Really?

I haven’t got a clue. No, I don’t listen to much pop music.

Excellent! It’s The Beatles.

It could be me on sax. Is that McCartney? I’ve done things with him, yeah. He likes Sidney Bechet, you know.

What do you think of the drumming?

Well, most drumming is terrible to me. Most of it’s intrusive. I do like good drummers, but as Chet Baker said, you’ve got to be a bloody good drummer to be better than no drummer at all. I find them insensitive – their sense of dynamics, for instance, is sadly lacking. But there are some very fine ones, in this country. I’m not gonna mention who they are. But back to McCartney, I did do a Dixieland thing with him once and he complained because we didn’t play it the same way twice. But he likes Sidney Bechet, so he can’t be all bad, no.

So you might be on this record?

I might be. If it is me, I’d like to know because I can tell PAMRA and get money every time that’s played. We should have been getting money for years and years and years just for being on things that are played on the air. They did in Europe, but we were way behind on that. See, you didn’t think at the time, you just played. So that was The Beatles.

You didn’t follow them much, then?

No, only when I played for ’em. I was aware of a couple of the tunes they wrote. “Yesterday” is a good ballad, and I suppose “Michelle” is an interesting tune. The chords are quite chromatic.

But harmonically they don’t compare well with a good Broadway tune.

Oh no – now you’re talking. I love Broadway shows – I adore them. I love those composers, you know, the Gershwins, the Porters, the Arlens, the Kerns.

They had a strong command of harmony, but I think the Beatles kind of found it by accident and there were always gaps in their knowledge.

Oh yeah – Cole Porter studied under Vincent d’Indy, and Gershwin had good teachers too.

They were pulling in Debussy, Ravel and the rest.

Oh yes – all that. Wonderful, great stuff.

And there was Borodin lifted almost note-for- note in that “Strangers In” something.

Ah yes – Kismet – “Stranger In Paradise”.

SOFT MACHINE

Slightly All The Time, from Third (1970)

Elton Dean (as, saxello); Lyn Dobson (f, ss); Nick Evans (tb); Jimmy Hastings (f, bcl); Rab Spall (vn); Mike Ratledge (ky); Hugh Hopper (b); Robert Wyatt (d).

BGO CD180

I don’t know who it is. You can give me a clue.

They’re British, around 1970. There’s a connection with you in locality.

Oh, it’s Sinclair, or Caravan. No, it’s not, it’s Soft Machine.

There’s Elton Dean and Jimmy Hastings.

I don’t recognise Jim, unless he’s putting on that vibrato. See, I don’t understand why people use that fast vibrato – it’s very mannered. I suppose it’s the Sanborn influence.

It wouldn’t have been then, because Sanborn didn’t come up until later.

Well, anyway, there’s a nanny goat way of playing, with respect. I find it irritatingly mannered. It sounds like someone taking the piss, actually. There are very good players that do this. But I don’t understand – it’s almost like a laughing saxophone sometimes. I wanna hear forthright playing.

You’re not keen on vibrato generally?

Well, it depends who it is. The way Webster does it, for instance, that’s fine, but I just feel it’s put on. That’s what you do these days – you play with that kind of narcissistic, self-pitying sound. The other thing is, this kind of tune, it’s got some wide intervals and leaping around a bit, but they’re all minorish – well, it’s modal – but a lot of it sounds like waiting-for-the-end-of-the-world music. You don’t hear many major pieces – it’s always sort of doomy. If you use modes all the time, it’s bound to have an element of doom about it.

You could use major modes all the time. But this is probably the effect of Coltrane on this generation, isn’t it? All these wailing, aching minor vamps.

He took a lot of influence from the Orient, which is why he tried to make his soprano sound like that Indian instrument – what’s it called?

The nay or shawm, or something?

Yes, but this influence on the soprano sax can make it sound like a bad cor anglais a lot of the time. It should sound like a higher alto – it should sound like a bloody saxophone. I used to aspire to that sound but I don’t play the soprano much now because I didn’t much like the sound I was getting. There are some that sound good – Steve Lacy doesn’t make it sound like a bad cor anglais. I can understand Coltrane doing it because he was after something specific, but then it became everybody’s sound.

So that was the Soft Machine. I’m not bragging, but I started them, in a way. Ratledge and Wyatt went to my old school, the Langton, and they saw my name on the honours board and said, “Why don’t we start a band? Tony Coe’s done all right with Humph.” So I’m responsible for that. Wyatt’s done some lovely stuff. I’d love to work with him again. He’s broadened out artistically – he’s a very interesting man.

Ratledge and Jenkins ran a TV jingles company, I think.

That’s right – I did some things with them down in the Angel. And Jenkins did very well with some choral works – he must have done well because he doesn’t ring me up anymore to do jingles.

Do you think there’s something in the water in Canterbury that spawned so many notable musicians – you, Soft Machine, Caravan, Tim Garland and so on?

There’s too much fluoride I think, and chlorine and nitrates. That’s why we always drink the old bottled water when we go there.

FRANCO AMBROSETTI

Theme From Peter Gunn, from Movies, Too (1988)

Ambrosetti (flhn); John Scofield (g); Greg Osby (as, ss); Geri Allen (p); Michael Formanek (b); Daniel Humair (d).

ENJA 5079-2

Sounds familiar. Can’t remember what it’s called. I played it even, I think.

Composer?

Oh – is it Mancini? The theme from Touch Of Evil or one of those detective things?

It’s “Theme From Peter Gunn”.

Ah, of course – we used to play it. The thing is, with that sort of ostinato you can play anything over it. The modal approach saved a lot of people’s musical lives – you put a cat on the white keys of the piano and let it run around and play an F and C in the bass it’ll sound all right. It’s what Stravinsky called pandiatonic. The trouble is it was dangerous because you get these people who think they’re geniuses because they’re playing all these runs. But like I say, the modal thing is too easy. It has its place, but I miss the other kind of harmony you get with major, minor, tonal and chromatic harmony. Modal harmony is all too safe.

If it’s done well though you can tell when a player really knows what they’re doing because they play interesting shapes over the vamp.

Oh yes – it’s very challenging to do it well.

I think changes-playing is more fashionable among educators now, but 20 years ago those Jamey Aebersold records with Herbie Hancock tunes such as “Maiden Voyage” created an easy entry point for jazz teachers and students – very few key centres and a dead-slow harmonic rhythm and you could sound immediately effective and moody without adding much content.

Yeah, I’m afraid so – people should be able to play “All The Things You Are” as a good basic tune to improvise on.

Your Mainly Mancini album took an approach that was different to the one on this tune, didn’t it?

Yeah – I don’t like a lot of it. It was too rushed. For some reason it’s quite popular, but I would have done quite a few of the things again if we had had time. Mancini is one of the last of the great classic songwriters, but that album, unfortunately, was done on a shoestring.

SPONTANEOUS MUSIC ENSEMBLE

Karyobin, Part 6, from Karyobin (1968)

Kenny Wheeler (t); Evan Parker (ss); Derek Bailey (g); Dave Holland (b); John Stevens (d).

CHRONOSCOPE CPE2001-2

Yeah – Boulez is right. See, it’s simple-minded. As I see this music, they heard some Schoenberg, Boulez and other people that write structured music – and it does show when it’s written to a system, even though to them it just sounds like a lot of squeaky-gate music. It’s almost like they’re taking the piss out of that music. And I don’t have any time at all for it. No, sorry. They’re probably very good players – in fact I wonder who they are? Am I on it?

Well, you’ve played with one of the blokes here. It’s Derek Bailey.

So it’s Company?

It’s before Company, I think.

Is Evan on it? Yeah? Sorry, Evan. But maybe even Evan doesn’t like it too much.

He does play by himself a lot these days.

Yeah, I don’t blame him. I just find this cynical and simple-minded: “We can do that.” Schoenberg? “Yeah.” Stockhausen? “Yeah – you just go plinkety plonk.”

Maybe there’s some sort of political dimension here – the emancipation of the note, every note is equal to every other note and we have a democratic musical conversation free of the shackles of traditional form, etc, etc.

Yeah, all that. But that’s not the way they’re playing. They haven’t that democracy in the way they play. There’s so much chance you could have four Gs together. There could be ways of rationalising it and ameliorating what it really is. But it escapes me. I find it completely pointless. Sorry.

When you played with Derek, did you do something similar?

Yeah, but there were only two of us, so you didn’t have this clash of musical personalities. So that kind of worked. We did a thing called Time and there’s some good stuff on it. None of it was written and the only things that were sort of given were tempo – very fast, very slow and so on. I did a mostly free record with Roger Kellaway too – but it’s got a blues at the end, too.

ANTON WEBERN

Sehr lebhaft, from Five Movements op. 5 (1929) Berlin Philharmoniker, conducted by Herbert Von Karajan.

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 423 254-2

Is it a person normally associated with jazz?

No, it’s the real thing.

It’s not Webern is it? I don’t know this too well, but it’s structured and you can tell as soon as you hear it. Even if you didn’t know what he was doing with the row you could tell intuitively this is serious music.

I was looking for some Alban Berg, but couldn’t find it, so I thought I’d bring something close. I know you like Berg.

Course I do, yeah.

You said you were eclectic, but it’s unusual to find someone who has an ear for both the second Viennese school and relatively sweet mainstream jazz.

Yeah, but I did study this kind of music with Alfred Nieman (that’s Paul Nieman’s father, by the way). I did a lot of analysis of this kind of music and in so doing I came to understand it and like it – especially Berg.

There’s no contradiction then in a taste for both Alban Berg and Ruby Braff?

No – the first prerequisite is that it should be honest. Then you think about the craft and construction. That’s why I love Louis Armstrong, of course – to me he’s completely honest – and Bird too. You feel they mean every note they play. That’s not easy – as I well know.

Ah well, every one’s got to make their way in a fallen world.

JAN GARBAREK/THE HILLIARD ENSEMBLE

Regnantem sempiterna, from Officium (1993) Garbarek (ss); The Hilliard Ensemble (v).

ECM 1525

Is this Garbarek?

Yes.

Oh, good.

Why good?

I’ll tell you in a minute.

(A few moments later)

I just wanna hear him come in and bugger it up. There he is.

So what’s your honest opinion of this?

I like the original. I don’t wanna hear this. What’s the point of doing that? Why doesn’t he make his own choral piece and bugger that up ? It’s all kind of moody – very contrived and manipulative. He’s a very good player, of course, but this is very easy – it’s all on one mode. I’ve heard him play on things that are more chromatic in which he’s riding roughshod over the harmony. This is one of the better pieces on this record because it’s easier. He’s taken a lot on, I think. I’ve heard him play on some ancient music where it’s more chromatic and he’s tried to improvise on it and it’s not easy. The harmonic rhythm is subtle – it’ s not like jazz , with one bar of this and one bar of that. The harmony changes in odd places and in odd ways, and to improvise over that is extremely difficult. But why not leave it alone? This one’s easier – it’s in E minor I think and so he can just play on his F#. I can’t see any point in it. It really is gilding the lily, or trying to. Leadening the lily, more like. I don’t see any point at all, except for making a lot of money.

You played quite a lot of early music in Matrix, with Alan Hacker. How did you approach that?

We played some very early and some very late music – stuff by Harrison Birtwistle and so on. I admit we did it then, we did have improvisation on some early music, but it was Alan’s idea, not mine.

Did you think it was a good idea?

I don’t know. It seemed to work. I liked it because we played some beautiful pieces, including Mozart, that we didn’t improvise on.

You talked earlier about Alan Hacker’s influence on you – could you expand on that?

Well, it was his approach to the clarinet – sound and timbre in particular, but also his musicality, because he’s such a fine musician. The way he thinks about music had a huge influence on me. I admire him very much indeed.

Did he influence the way you play jazz?

Well yes, he did ultimately because I was exposed to other music and became broader, and the actual clarinet sound was a big influence.

ANDY SHEPPARD

Oscar & Lucinda, from Dancing Man & Woman (1999)

Sheppard (ts); John Parricelli (g); Steve Lodder (ky); Steve Swallow (b); Chris Laurence (b); Paul Clarvis (perc); Kuljit Bhamra (tabla).

PROVOCATEUR PVC 1020

Is it English?

Yes.

Tim Garland?

No.

It’s not Sulzmann is it?

No. It’s yet another Canterbury connection – this time through the record label.

I wanna hear him improvise – but I think it’s whatshisname from the West Country – Sheppard, Andy Sheppard. You know, it’s pleasant enough stuff. It almost sounds like incidental music to a French film. It’s well played and…

It reminds me of something that might find a place on Jazz FM’s Dinner Jazz.

Well, I’ve heard things enthused about on Dinner Jazz which were really defective. If you’re lucky you get a bit of Ben Webster or Norma Winstone but they seem to enthuse about things on which people are playing wrong notes. We all make mistakes sometimes, but there are holy cows whose defects can never be mentioned. Much of what they play is pretty mediocre, as if they’re interested in the effect rather than the substance.

SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

AS LEADER:

Swingin’ Til The Girls Come Home (1962, Philips)

Zeitgeist (1976, EMI)

Coe-Existence (1978, Lee Lambert)

Mainly Mancini (1986, Nato)

Canterbury Song (1988, Hot House)

Nutty On Willisau (1983, hatART 1983)

Some Other Autumn (1993, Hep Jazz)

Blue Jersey (1996, AB)

Captain Coe’s Famous Racearound (1996, Storyville)

WITH OTHERS:

Derek Bailey: Time (1979, Incus)

Roger Kellaway: British-American Blue (1978, Between The Lines)

Alan Barnes: Days Of Wine And Roses (1998, Zephyr)

Tina May: N’Oublie Jamais (1998, 33 Jazz)

Alan Hacker: Sun, Moon & Stars (1999, Zah Zah)

Anthony George Coe (29 November 1934 – 16 March 2023)