Barney Bigard and Duke Ellington seemed to have an almost supernatural understanding as their partnership grew. Ellington’s ability to write for his players to bring out their best probably peaked with Barney. Then came Jimmy Hamilton to open another door to allow Duke to write suites that combined the best of jazz with the dignity of the symphony.

This convention was deceptive, for the sound of the suites, often just long pieces thrown together, thankfully remained Ellingtonian and the illusion of the symphony was created by Hamilton’s conventional orchestral sound on clarinet.

Duke’s first major suite, Black, Brown And Beige, caused much excitement before it was premiered. John Hammond and Leonard Feather, the two main New York critics who were known more for their squealing and bitching at each other than for any constructive approach to the music, were amongst the first to change course and slam the music. (Both men bragged of being close friends with Duke but the “closeness” simply allowed them more easily to stab the composer’s back, which they did with depressing frequency. They did the same to Louis Armstrong.)

Black, Brown And Beige never got a fair chance and even when it was recorded to appear on four 12″ 78 sides it was truncated to fit the medium. In fact listening to that 1944 version now, it doesn’t sound half bad, and is certainly lit by the performances of Johnny Hodges, Taft Jordan, Ray Nance, Joya Sherrill and others.

The suite, on the RCA label, illustrated the fact that when music has a political message – it was intended to portray “the history of the Negro in America” – the impact of the music suffers badly.

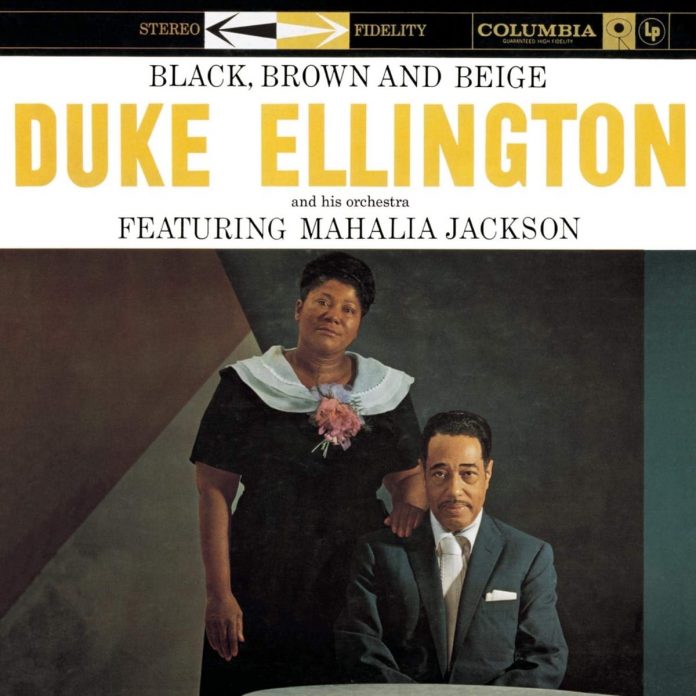

It seems likely that Duke felt he had been unfair to his composition, and that may be why he returned to record the suite again for Columbia in February 1958. The “Black” movement was a success but the rest of the suite suffered from a haste which was becoming familiar. The soloists did well with a notable Come Sunday from Harry Carney, replacing Johnny Hodges who was off somewhere working with Billy Strayhorn) and the addition of Mahalia Jackson, always an imposing singer.

Ellington did occasionally fail his own classic compositions in this way. In the case of Diminuendo And Crescendo In Blue, so prized for its perfect three-minute form, I must hand over to my much missed friend and mentor Max Harrison.

“The sensational ‘success’, which is to say rape and murder, of this item at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival, while a source of great pleasure to Ellington, is irrelevant because it depended on Paul Gonsalves’s absurdly over-extended 27-chorus solo, not on the character and substance of the work itself.”

But when Duke got the suites right, he rose above everyone else in jazz. I will never forget how I felt stunned and exhilarated (still do) when first I heard The Tattooed Bride. Duke’s conception sounded miraculous and the spaces that he left for Jimmy Hamilton allowed the clarinettist to have an authority over the whole work. Bigard might have taken a lot away from the Ellington orchestra, but the presence of Hamilton and his impeccable classical sound opened new vistas for the Duke.

The band had been playing the 12-minute suite for some time before it was recorded. It was premiered at Carnegie Hall on 13 November 1948 and was finally recorded for Columbia over a month later. The piece was obviously thoroughly rehearsed and there is very little improvising by the soloists. Trombonist Lawrence Brown is the first voice to be heard and at one point there is a spectacular scored descending phrase handed from Johnny Hodges to Paul Gonsalves before bottoming out with Harry Carney. Jimmy Hamilton’s smooth and sedate passage tumbles into uptempo and he creates a virtuoso climax of riding over the band which would have put Goodman to shame.

At the session two vocals were sung by one of Duke’s better vocalists, described simply as “Yvonne”. This was Yvonne Lanauze, who was to leave the band to marry in 1952 and who has been Eve Duke ever since. She still works successfully as a pianist and singer in Vancouver at the age of 96.

The writing and orchestration of Such Sweet Thunder is magnificent, but the suite is broken up into short pieces that hark back to the 78 era in length, and the suite never becomes a whole.

Hamilton had a vital and eloquent role in Tone Parallel To Harlem, one of Ellington’s favourites of his longer compositions whose title was swiftly shortened to Harlem. It was played often in concert, but the best version predictably remains the Columbia studio version recorded on 7 December 1951. Louie Bellson had a crucial role throughout and gives a wonderful display of drumming. The piece is mostly ensemble from the band, but individual voices constantly emerge and Hamilton has a notable and poised solo with the orchestra’s backing accumulating behind him. The theme he was awarded by Duke is indeed lovely and, as throughout the piece, the work of the trumpet section is filled with power. Lawrence Brown carries the wistful theme before Jimmy’s return. Bellson powers the ultimate climax and its release with exultation.

As a result of the moving success of Tattooed Bride and Harlem one is tempted to regard the two bands involved as the best of Duke’s later period. I certainly do. In between the two recordings Johnny Hodges, who considered himself underpaid, left to form his own small group, taking Lawrence Brown and Sonny Greer with him to work for Norman Granz. With Granz behind him, Johnny’s band became a rapid success. Duke was knocked sideways by the departures, but tried to fill the hole in the dam with the Great James Raid on Harry James’s band, giving him one of his best ever section leaders in altoist Willie Smith, the returning Juan Tizol on valve trombone and of course one of his greatest ever drummers in Bellson.

When Ellington eventually signed the band with Norman, he and Granz connived to choke off business for the Hodges small band with the result that Johnny, who didn’t know about the plot, returned to Duke’s big band in 1956.

Jimmy Hamilton finally left the band in 1968, having been in the reed section for 25 years.

He was a little strange about money. Apparently he had a portable mini-bar which he always took with him as the band toured and from this he would sell drinks to the other musicians. He left the band owing Clark Terry some money that he had borrowed. Clark was hurt and of course annoyed when Jimmy didn’t repay this, even after he had had his lottery win.

See part one of this article

See part two of this article

See part three of this article

Postscript

Four hours after I’d sent this piece in the twin-CD of Duke Ellington at Cornell University in 1948 (Nimbus 2727/28) arrived. It has a live version of Tattooed Bride which the band plays with great enthusiasm. The

sections are clear, but not terribly well balanced and Jimmy Hamilton’s vitally important soloing is recorded to perfection. The album is packed with rare and good stuff which almost makes one forget one’s rage at the fact that one CD is only 54 minutes long and has, for no given reason, had several tracks removed from it.