The first time I heard Mabel Mercer my reaction was succinct: You’ve got to be kidding! And that was the reaction not of a callow youth but someone well into his 30s. But within weeks a volte face had occurred that was so complete that Mercer had for me metamorphosed into the benchmark, the one they all had to beat.

This Road-to-Damascus moment occurred at a time when although I hadn’t actually heard Ms Mercer, I had heard a lot about her from some seriously heavy hitters – Whitney Balliet and George Frazier, two titans of jazz journalism. Hype has a way of blowing up in the perpetrator’s face. But with Mabel the hype was an understatement.

But can the words jazz and Mabel Mercer be juxtaposed in the same sentence without attracting negative comment? Were I to delete Mabel Mercer and substitute Frank Sinatra no one would turn a hair. Nor if I put Billie Holiday in place of Mabel Mercer. The point is that both Frank Sinatra and Billie Holiday said that everything they know about their day jobs they learned from Mabel Mercer. When you hear Sinatra sing “Night anD Day…” hitting both Ds right on the nose and clearly separating them you’re hearing Mabel Mercer at one remove and half a tone lower.

Mercer was born, out of wedlock, in 1900 in Burton-on-Trent, Staffordshire, the home of draught Bass and Worthington E, to a black American musician who promptly dropped off the radar and an itinerant white English music-hall performer from a family rich in such specimens and with little or no maternal instincts and no interest in or intention of quitting show business in favour of domesticity.

The infant was shuttled between relatives before being enrolled in a convent school from which she emerged at the outbreak of World War One to go “on the halls” with an aunt. With radio not even a glint in Marconi’s eye and only silent films as competition it was still possible to make a living in variety. Soon the duo were supplementing dates on the continent with those in England. By the 1920s Mabel entered the second of the three phases of her career when she settled in Paris.

By coincidence a black American woman some six years older than Mabel, Ada Smith, better known as Bricktop, from West Virginia, also settled in Paris, opened a club at 66, Rue Pigalle and hired Mabel as what we would call today a “greeter” cum singer. The problem was that Mabel found it difficult to be heard in a noisy club so Bricktop encouraged her to sit at individual tables and sing directly to that table and then employ a megaphone for the room in general. In this way Mabel learned to concentrate on lyrics rather than music and soon celebrities – the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Cole Porter, Julius Monk, etc – were coming to the club just to hear Mabel.

In the late 30s Herr Schickelgruber made his presence felt at stage left and Mabel exited stage right via the Queen Mary which deposited her in Manhattan, triggering phase three of her career. She spent seven years at Tony’s, a small club located at 39 West 52nd Street, proof, if indeed proof were needed, that those English musicians known as Geraldo’s Navy erred in their belief that 52nd was home only to the Onyx, Hickory House, Famous Door, Three Deuces, and other celebrated jazz clubs. There was room also for Tony Soma to provide a forum where an English lady from Burton-on-Trent was able to refine the art of merely sitting and singing.

‘No funny hat comics, no chorus girls, no party gee-gaws. Just Mabel. She came as a favor to a friend and left a score of club owners weeping because she would consider nothing so commercial as a return engagement’

Fate brokered a rendezvous between Tony’s and the wrecking-ball, so Mabel moved from West to East 52nd Street, specifically The Byline Room of the East Street Side Show Spot at 137 East 52 Street. She remained there until both The Show Spot and The Byline Room burned down in 1955. With a strong and loyal following – on any given night the Windsors, Eileen Farrell, John Gielgud, Jose Ferrer, Zachary Scott and John Huston would rub shoulders with less illustrious fans – Mabel saw no reason to leave Manhattan and seldom did so. But writing in Playboy about a one-off appearance she made in Chicago, Victor Lownes said “She packed that nightclub (the Blue Angel) with over 800 turned away at the door. This, mind you, in a city where she had never appeared before, on a Sunday, normally the deadest night in the nightclub week, and with an admission charge of $5.50. No funny hat comics, no chorus girls, no party gee-gaws. Just Mabel. She came as a favor to a friend and left a score of club owners weeping because she would consider nothing so commercial as a return engagement.”

That’s quite a send-in and I can hardly let out a squawk if the odd reader who isn’t actually hip to Mabel is beginning to murmur “This is all very well, but what does she actually do?”

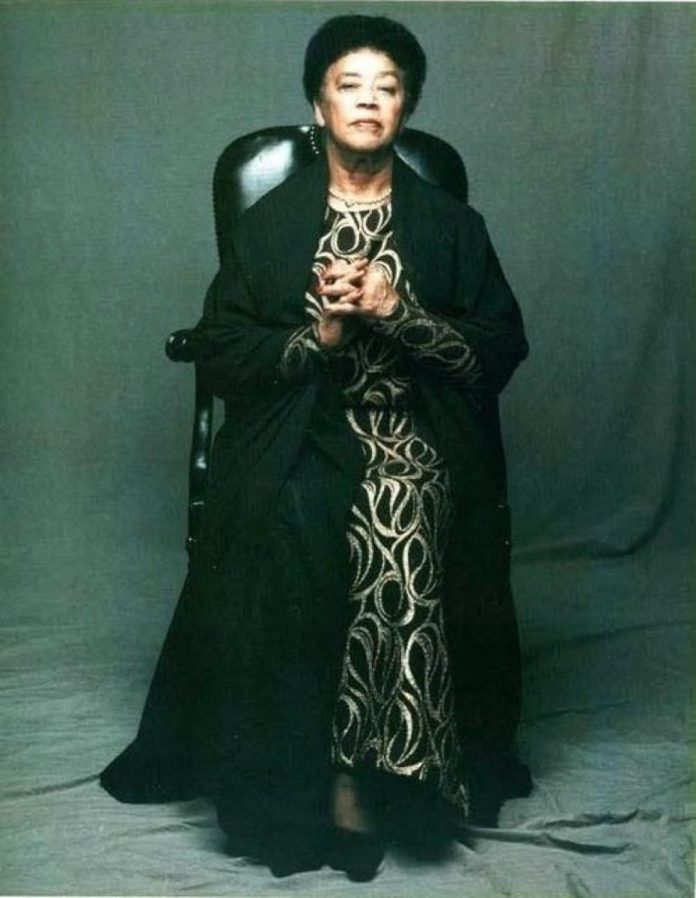

I can only reply, well, nothing really; she sits in an armchair, ramrod straight, hands in her lap, shawl draped across her shoulders, with seldom anything larger than a piano – or two – as accompaniment. Before the auditors’ very eyes she metamorphoses into Scheherazade, beguiling them with tales of lost youth, lost love, neglected dreams, majestic goals, yesterday squared.

Frank Sinatra once said to fan Walter Richie “If you want to see me in New York I am at The Byline Room on East Fifty-Second Street every night. There is a singer there by the name of Mabel Mercer who I think is great. When you see her you’ll know why I feel as I do.”

The key word in that third sentence is “see”, because, seldom more than 50 feet from even someone at the back of the room she is not so much singer as actress, wringing every last nuance out of the tale she is telling.

In one sense she was her own worst enemy. With her reluctance to leave New York, her penchant for small, intimate venues, her limited discography (no more than 10 solo albums plus two live ones from the two Town Hall concerts) – she contrived to limit her fan base yet only succeeded in increasing it.

I can vouch for the fact that her voice alone on disc is sufficient to sell her – and when one thinks about it just how many aficionados would have been able to see her in normal circumstances? Answer: those within striking distance of Manhattan and able to shoehorn themselves into a tiny space.

I was lucky because in 1977 she played a short season at the Playboy Club in Park Lane and I called in sufficient favours to obtain a virtually impossible-to-get ticket. By that time, of course, I had long owned all her available recordings and had spent literally hours time travelling from a listening room in London to a magical can’t-see-the-join blend of Shangri-La and The Emerald City, where the most outrageous tales come across as plausibly as News At Ten, especially if told to music.

From dozens of examples I’ll confine myself to just one: in 1961 Bob Merrill wrote words and music for the successful Broadway show Carnival. It was centred on an incredibly naïve young girl who leaves her small town and gets a low-paying job in a circus and totally believes that the puppets in one of the sideshows are actually alive and can and do talk to her – older readers to whom this seems familiar are correct, the show is a musicalisation of the 1950 MGM film Lili. In an early scene she talks about her (to her) incredible journey to get to the circus – “I came on two buses and a train. Can you imagine that? Can you imagine that? Two buses and a train.” The star of the show, Anna Maria Alberghetti, was 25, albeit passing credibly for 18.

When she sang those words, Mabel Mercer was 61, yet she had no trouble convincing her audience that she was that naïve young girl. The phrase “Can you imagine that?” recurs six times throughout the lyric and Mabel is more convincing each time.

Then was then and now is now and one of the few positive things about Now is that since Then we have come up with YouTube, so we can all see Mabel live. It’s not vintage Mabel, it’s Mabel aged 70+ but it is vintage magic and it’s not hard to close your eyes and imagine you’re sitting in Tony’s on a typical evening. Mabel shows up with a group of friends around 11 p.m., possibly straight from the theatre. She works the room, a room packed with her friends and fans who are interchangeable. Around midnight a couple of waiters bring out her armchair and place it adjacent to the piano. Her accompanist, Bart Howard, Jimmy Lyon, Buddy Barnes – whoever – is already there, half in the bag just by proximity. She begins to sing and Now disappears imperceptibly; Nostalgia takes the stand and next thing you know it’s 4 a.m. and the milkman’s on his way.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times and you’ll never know how sorry I am you couldn’t make it. It would have truly enhanced your life.