Contemporary jazz lost one of its major voices when the Norwegian drummer, percussionist and ECM recording artist Jon Christensen died in his sleep, in Oslo, on Tuesday 18 February, a month or so short of his 77th birthday. When Eberhard Weber and I discussed the sad news, Weber’s summation was incontestable: “He was a wonderful player”. Manu Katché considered him “a poet and a colourist who could make the drums sing”, while for Peter Erskine, Christensen was “an absolute master, especially in matters of dynamics and transition. Like many, I learnt a great deal from him”.

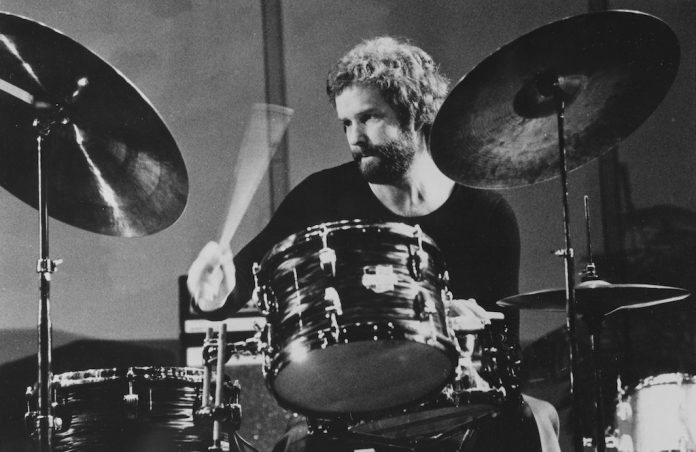

Whether using sticks or brushes, mallets or his bare hands, Jon Christensen was a magical musician for whom the ceaseless innovations of drum technology meant very little. His artistry rarely required anything beyond snare, bass and two toms, hi-hat, ride and (little) crash cymbal, with his beloved original K-model Zildjan cymbals a constant presence. As John Surman says, from such a conventional set-up, “Jon created a completely fresh and absolutely personal style of jazz drumming. Pretty amazing, really!”

Steeped in the history of his instrument(s), Jon set that literacy in the service of both considerable, driving polyrhythmic power and an organic sensitivity to space, time and tone that could conjure the subtlest cross-rhythmic ebb and flow of accent and texture, sound and silence. An improviser of exceptional intuition with a keen sense of humour, an appreciation of the visual arts and a life-long love of sports (especially ice-hockey and football) Christensen produced shape-shifting figures that carried the conviction of composition. When Tommy Smith recorded Azure, his 1995 Linn Records tribute to Joan Miró, he thought so highly of Christensen’s contributions that he shared the composer credits with him.

Apart from the eponymous 2004 ECM :rarum release of some of his favourite tracks from his work on the label, a long and exceptionally rich career saw only two releases headlined by Christensen. Both are collaborative affairs: the 1976 Zarepta album No Time For Time with Pål Thowsen (d), Terje Rypdal (elg) and Arild Andersen (b) and the 1991 Odin CD Knut Riisnaes /Jon Christensen featuring John Scofield (elg) and Palle Danielsson (b) – the latter with a cover image by Frans Widerberg, one of Christensen’s favourite painters.

However: valuing group interaction above all else – what he called “band feeling over bravura” – didn’t stop Christensen from skipping bar lines and drumming in what he described as “waves”: on the contrary. He thus did much both to reconfigure what it could mean to be a strong individual in the music and to open up, intensify and expand “band feeling”. The legacy of such an intelligent and enlivening approach is evident in the work of contemporary Scandinavian drummers such as the Norwegian Thomas Strønen (born 1972) and the Swede Jon Fält (born 1979).

Born in Oslo, 20 March 1943, the young Christensen played piano at home before a feeling for drums led him into local rock ’n’ roll and skiffle bands in the mid-1950s. He soon graduated to swing and bop, playing in the Gunnar Brostigen Big Band and also in a quintet led by pianist Finn Melbye, Christensen’s cousin. In 1960 that quintet won the 1960 Norwegian Amateur Jazz Championship, which led to various invitations to Christensen to play around Norway and, in particular, at the Metropol Jazz Club in Oslo.

It was here that Christensen’s early jazz career really took off. Prentice nights supporting the likes of Bud Powell and Dexter Gordon fed into more exploratory work with the Karin Krog Quartet, which in 1964 made a successful appearance at the Antibes Jazz Festival. A year later the innovative singer and improviser received the prestigious annual Buddy Award from the Norwegian Jazz Forum and Jon followed suit in 1967. Karin recalls: “At 20 Jon was already an accomplished drummer, always supportive and full of creative ideas. I was lucky enough to have him with me on four of my albums – By Myself (1964), Jazz Moments (1966), Gershwin With Karin Krog (1974)and We Could Be Flying (1974). On the last, Jon’s interplay with bassist Steve Swallow is quite astonishing”.

Also present on (two tracks of) Jazz Moments was Jan Garbarek. My Jan Garbarek: Deep Song (1998) and “Jon Christensen: Drumming With Open Ears” in JJ 09/06 and 11/06 detail these two young players’ shared early development, when they drew initial local inspiration from the modally oriented pianist Arild Wikstrøm. They went on to develop fresh musical ideas with early key collaborators Terje Bjørklund (p), Arild Andersen and Terje Rypdal and, a little later, Bobo Stenson (p). Invaluable stimulus came from playing with George Russell and Don Cherry during their various sojourns in Oslo and Stockholm in the mid-to-late 1960s. Bjørklund aside, these young Scandinavians would all go on to tour and record with Russell, who (like Cherry) did much to bring their work to the attention of an increasingly broad and appreciative international audience.

In his sleeve-note for George Russell Presents The Esoteric Circle, recorded in Oslo in 1969 by Garbarek, Rypdal, Andersen and Christensen, Nat Hentoff spoke of Christensen as “a pre-eminently musical drummer”. Looking back, Jan Garbarek characterises Christensen as “a unique, naturally talented player with a great musical understanding. Jon had a rare ability to lift any musical collaboration he cared to take part in”. Many such collaborations between Garbarek and Christensen were recorded, from the mid-to-late 1960s through to the 1981 Paths, Prints by the Jan Garbarek Group with Bill Frisell (elg) and Eberhard Weber (elb). Bobo Stenson’s studio legacy with Jon includes his trio album Underwear (1971) with Arild Andersen; Witchi-Tai-To (1973) and Dansere (1975) by the Garbarek-Stenson Quartet with Stenson’s compatriot Palle Danielsson, and Stenson’s further trio albums Reflections (1993), War Orphans (1997) and Serenity (1999), all with Anders Jormin (b). The decade from 1982 to 1992 witnessed one of the most productive of all such collaborative ventures in the Masqualero quintet which Arild Andersen ran with Jon and Tore Brunborg (ts, ss), Nils Petter Molvaer (t) and first Jon Balke (p, kyb) and then Frode Alnaes (elg). There were four albums, the first on Odin, the last three on ECM, generating tours around the world and gaining three awards of the Spellemannsprisen (known as the Norwegian Grammy).

Equally remarkable examples of Christensen’s musicality can be found on the Norwegian albums Briskeby Blues (1969), Hav (1970) and Ingentings Bjeller (1977) by the Taoist-like poet Jan Erik Vold. All were reissued in 2009, with extensive contextual documentation, in the Plastic Strip box CD set Jan Erik Vold: Vokal. The Complete Recordings 1966-1977. Further notable work can be heard on, for example, the Norwegian-Bulgarian singer Radka Toneff’s Winter Poem (1977), Norwegian pianist, composer and arranger Per Husby’s Your Eyes (1987) and Swedish bassist Lars Danielsson’s Poems (1991) and Far North (1994), both with Bobo Stenson and Dave Liebman (ss), and Libera Me (2004).

It was at ECM that Jon’s genius was to be most comprehensively documented. This included a magnificent body of work with his aforementioned circle of Scandinavian colleagues, who came to include Sidsel Endresen (v) on her albums So I Write (1990) and Exile (1993), the latter including Jens Bugge Wesseltoft (kyb); Palle Mikkelborg (t, flh) – with whom Jon contributed to Terje Rypdal’s Waves (1977), Descendre (1979), Skywards (1996) and Vossabrygg (2003) – and Ketil Bjørnstad (p) and such intensely lyrical albums of his as The Sea (1994) and Remembrance (2009). If Bobo Stenson’s two-CD Serenity (1999) with Jon and Anders Jormin exemplifies the quality of all such Nordic projects, an extraordinary range of albums featuring musicians such as John Abercrombie, Anouar Brahem, Keith Jarrett, Charles Lloyd, Ralph Towner, Dino Saluzzi, Tomasz Stanko, John Surman, Miroslav Vitous and Eberhard Weber testifies to the universal reach and resonance of Jon’s poetics.

To the end, Jon’s creativity ran wide and deep, despite his suffering poor health for several years. After surviving throat cancer, the last two years saw the onset of dementia as a series of falls necessitated a move to a care home. But he played at major festivals in Copenhagen and Aarhus in 2018 with Palle Mikkelborg and Jakob Bro (elg). Two years earlier Jon had recorded his final session for ECM, Bro’s quartet date Returnings, with Mikkelborg and Thomas Morgan (b).

In February 2018 Jon contributed drums and percussion to four of the five tracks on the eponymous Bugge Wesseltoft & Prins Thomas [aka Thomas Moen Hermasen] on the Smalltown Supersound label. He was billed as a “guest musician” but his spaciously cast, broken cross-figures and shimmering cymbal touches brought a sparely wrought yet completely integrated beauty to the ambient electro-grooves of Wesseltoft (p, kyb) and Thomas (elb, d, pc, programming). Recorded in April of the same year, the classically trained Russian jazz pianist Yelena Eckemoff’s Nocturnal Animals two-CD set on her L & H label presented Jon in a very different context. What would be Jon’s final recording found him at full register in the quicksilver yet meditative, lyrically oriented company of Thomas Strønen and Arild Andersen.

Arild was one of Christensen’s oldest friends and playing partners. He helped facilitate Jon’s final gig, a private affair which took place in December 2019 at Arild’s house in Oslo: “This was Bugge’s idea. We got Jon up to my place, where I have a drum kit always ready. Bugge and I and Jon’s partners from the Masqualero days, Tore [Brunborg] and Nils Petter [Molvaer], talked with Jon for several hours in the early afternoon, just relaxing and reminiscing. Jon had more or less forgotten the ECM Afric Pepperbird date from 1970, so we played it for him and he enjoyed it, I think. And then Jon went over to the drums and we took off for an hour or so on some of the old Masqualero material. And you know, Jon played great; he was really there, alive again in the music. A special coda to a special life, you could say”.

Jon’s funeral took place at midday on Friday 28 February at a packed Sagene Kirke in Oslo. The entrance music and subsequent pieces were played by Bugge Wesseltoft and Arild Andersen, Jon Balke, Nils Petter Molvaer and Tore Brunborg; there was a church organ piece and Bobo Stenson played Bill Evans’s Your Story. The ceremony – where Arild Andersen had spoken – concluded with a specially written funeral march, or exit piece, by Jon Balke, for brass, reeds, drums and percussion. Celebration of Jon’s life then continued, from mid-afternoon onwards, at the famous old Club 7 venue in downtown Oslo, with participants including Jan Erik Vold, Ketil Bjørnstad, Live Marie Roggen, Audun Kleive, Ine Hoem, Per Oddvar Johansen and Knut Reiersrud.

Jon Christensen is survived by his wife Ellen Horn, the actress, theatre director and sometime Norwegian Minister for Culture; by their daughter Emilie Stoesen Christensen, the jazz singer and actress who made her recording debut on Jon Balke’s Batagraf album for ECM, Say And Play (2011), and by Jon’s daughter Jannicke C. Dahr from his first marriage, who works at “Fond for Utøvende Kunstnere” supporting musicians in matters of concert and travel logistics.