“It’s not dated in any way,” declares guitarist Terry Smith of the recently released If Live At The BBC, a set of previously unreleased 1970 and 1972 tracks by the pioneering fusion band If, of which he was a member.

In fact the performances of the songs on the double CD are sometimes superior to the versions that appeared on the four studio albums that the band originally released. “Well, you can stretch out live but in the studio you’re limited to a certain time so you have to cut the solos,” agrees Smith.

If’s main composer was saxophonist Dave Quincy. “Dave was a good writer,” says Smith. “I wasn’t a good reader but he would come in and say ‘Play on these chords,’ and that was fine for me. I could play whatever he said. [Saxophonist] Dick [Morrissey] and I were the main soloists in the band – on a gig if we did 10 tunes I may have soloed on eight – and I think Dave basically wrote the way we played.”

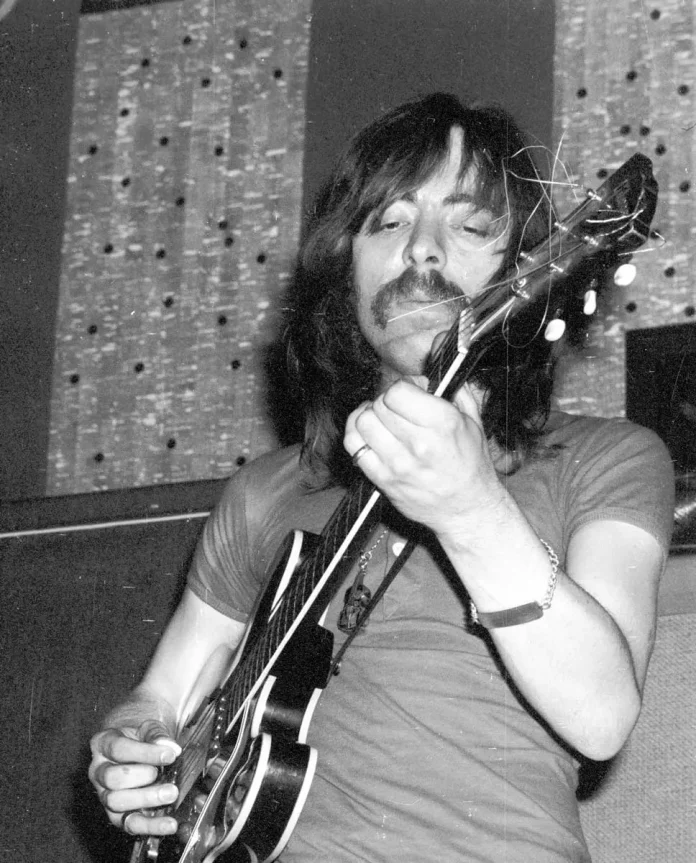

‘I just use the amp and the guitar. And I used the heaviest strings possible and before I switched to the fingerstyle thing I used to use a very heavy ivory plectrum that was almost an eighth of an inch thick’

Smith characteristically plays with a beautiful, undistorted tone on the album. “I liked a softer tone,” he says. “Basically I came from bebop music and that was the sound I wanted. That was my identity. I never liked the tinny, screeching rock ’n’ roll style. I just use the amp and the guitar, never any [effects]. And I used the heaviest strings possible and before I switched to the fingerstyle thing I used to use a very heavy ivory plectrum that was almost an eighth of an inch thick. I used to make my own. And that was part of the softer sound I wanted. Probably it was a little soft for chord work but it was ideal for solos and basically I was only playing lead guitar. I’m not a chord player so a softer sound suited me.”

On two versions of I’m Reaching Out On All Sides, recorded for shows introduced by Brian Matthew and John Peel respectively, Smith creates an enchanting Indian raga-like effect. “Quincy wrote the song in 7/4, a weird time-signature, and it was like an Indian scale. I played an open string against the top string and it was effective,” remembers Smith.

He acknowledges that he hadn’t studied Indian music. “No, but at the time Ravi Shankar and all these people were around and the Beatles used to do that sort of thing and I’d worked a lot with Harry South who lived in India for a while and wrote certain things so maybe that rubbed off and it just fell into place. It was nice to do.”

On winning Melody Maker’s Best Guitarist Award in 1968: ‘For the first year the front row would be all guitarists with arms folded’

Even before he joined If, Smith’s talents were recognised when he won Melody Maker’s Best Guitarist Award in 1968, a huge accolade in that era. “It was amazing,” he recalls. “A very good feeling. But also daunting because I used to do a lot of out-of-town work with local rhythm sections and for the first year the front row would be all guitarists with arms folded. They wanted to knock you. It was weird. And hard work.”

One of Smith’s crucial early bands was the Tony Lee Trio. “We played – I suppose you’d call it – hard bop. I virtually lived in the Bull’s Head with the Tony Lee Trio and with Dick Morrissey. It was running seven nights a week and Sunday lunchtime and we’d end up doing five! And they were absolutely packed out. It was great.”

Smith later played with Ronnie Scott’s Big Band. “Ronnie was a nice guy and very easygoing,” he reminisces. “I was new in the band and the youngest and we were playing away one night and he sidled over and said ‘Turn it down, Tel.’ And I looked at him. And he says ‘Or up!’ Lovely! He was very easy to work with.”

Of the Walker Brothers: ‘Gary Leeds was the drummer and he wasn’t really a player so Mickey Waller used to sit behind the curtain and do the gig’

With Ronnie Scott’s band Smith backed Scott Walker of pop heart-throbs the Walker Brothers on one tour. He also accompanied the Walker Brothers themselves, who’d had number one hits with Make It Easy On Yourself and The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore, on a 1968 Japanese tour. “That was amazing,” he enthuses. “They were phenomenally popular there. [Walker Brother] Gary Leeds was the drummer and he wasn’t really a player so [ex-Jeff Beck Group drummer] Mickey Waller used to sit behind the curtain and do the gig so then you’d two drummers and sometimes it was very awkward. But you just get on with it.”

Smith actually enjoyed playing with the Walker Brothers. “Yeah, there were written arrangements and I’d a few things to play and I’d just come from playing jazz clubs in Britain and suddenly I’m playing in an auditorium to over 10,000 people. And they were talented singers.”

Scott Walker in fact produced Smith’s first solo album, 1969’s Fall Out, on which he is backed by musicians such as Kenny Wheeler. “It was the best of British jazz musicians. Scott knew what he wanted and I was satisfied with it,” says Smith. “Six tracks were with a big band, the other two were organ, guitar and drums which I loved. But I think it was done because Scott was a famous pop star and Philips, the record company, wanted to keep him happy. It was a beautiful album but they never pushed it.”

The same year Smith put in a stint with England-based American soul singer J.J. Jackson alongside future If colleagues Dave Quincy and Dick Morrissey. “It was a good band and fun. And a weekly wage for Dave, Dick and myself.”

On modern, college-trained players: ‘They know every tune, they know every change, they can play fast but it’s like clockwork. They’ve no bloody soul, no feeling’

Smith’s early dues-paying years are in contrast to the experience of most modern musicians who learn in universities rather than on the road. Smith is scathing about such players. “I’ve no time for them,” he asserts. “They know every tune, they know every change, they can play fast but it’s like clockwork. They’ve no bloody soul, no feeling.”

Forming If in 1969 massively raised Smith’s profile. “We were playing jazz solos over a rock rhythm section – a bloody good rock rhythm section,” he says. “But I never altered my style. I still played with a soft sound but it was much more exhilarating because when you do a jazz gig you play standards or bebop tunes. With If, Quincy was writing things where there were weird changes or you would just play on one chord and they were marvellous. It was freedom.”

Miles Davis, on hearing If in New York: ‘‘Well, man, they don’t sound white’

When If toured America, Miles Davis showed up at one of the band’s gigs. “Yes, funny that,” muses Smith. “He came to a gig in a club in New York. He didn’t stay long, just a few numbers, and then left. And Lew Futterman, our manager, asked him ‘What do you think of the band?’ and he said [and here Smith adopts a Miles-like croak] ‘Well, man, they don’t sound white.’ Which was great, coming from him. I suppose.”

If gigged with many of the fashionable rock bands of the day, including the Faces, with Rod Stewart and with Black Sabbath. “They were very nice but they didn’t play our music. A lot of them were more showmen than musicians. I remember once walking out holding my ears and then coming back to do our show! I wouldn’t say we dismissed the other bands – that sounds terribly arrogant – but it’s just that their music was on a different plane, totally.”

If avoided the worst self-destructive excesses of the era. “We might have occasionally done things on a night off but basically we were just heavy drinkers and it was amazing to be in America where the bars were open all day and night and you were out and enjoying yourself. It was a very social band. We spent a long time on the road and we all got on very well. There was no aggravation.”

But the band began to lose momentum. “When you’re forever on the road you can’t write material and we were running out of stuff to do. You’d go into the studio and you’d only have one new tune. We were doing like Glasgow one night, Nottingham the next night, then Cornwall. It was impossible. Particularly if you liked a drink. We’d been on the road for nearly three years and we got disheartened with the whole business.”

In 1972 Dick Morrissey fell ill and the band subsequently dissolved. Oddly, Morrissey reformed If the next year with new musicians, recording three further albums. “They tried to persuade me to do it but I was tired and was drinking too much and didn’t want to,” says Smith. “I’d seen what travelling on the road did to people and I didn’t want it.”

Following the original If’s demise drummer Dennis Elliott managed to make the really big time as an original member of the US-based Foreigner who had hits such as the worldwide number one I Want To Know What Love Is. “About two years later he was in Britain and he says ‘Come and see the show.’ So I went and there were all these 200-watt amps and they stuck it up and I thought ‘No, I can’t have this.’ It was absolutely impossible and I just left!” chuckles Smith. “No wonder they’re all stone deaf!”

Meanwhile the guitarist joined Zzebra, whose music contained African influences, along with Dave Quincy and Osibisa saxophonist Loughty Amao, and played on the band’s self-titled debut album. “Zzebra wasn’t really my music but it was fun,” reflects Smith. “But I didn’t last long because three years on the road with If was very, very tiring and I’d had enough. And the band all liked a joint and I didn’t so there was just a parting of the ways!”

‘I now play a cheap Gibson copy, an Epiphone. It’s 500 quid and I’m quite happy. It’s bloody heavy but it’s got a wonderful neck, a narrow neck and it suits me because I’m not a big man’

All the way through If and Zzebra and beyond Smith played a Gibson 330. “I loved it but it got stolen so I ended up with a 125 which I wasn’t very happy with. And then a guitar geezer sold me a Gibson 175 which was beautiful but you can’t take it on gigs. If you leave it, it’s stolen. I mean, you’re talking six, seven, eight, 10 grand. So I now play a cheap Gibson copy, an Epiphone. It’s 500 quid and I’m quite happy. It’s bloody heavy but it’s got a wonderful neck, a narrow neck and it suits me because I’m not a big man.”

In 2015 Dave Quincy recruited Smith for an If reunion which produced the If 5 album but Smith found the experience unsatisfying and the band didn’t gig.

The London-based Smith is now 79, and his days of major touring are long behind him. He does continue to work on the British jazz scene but he recently endured a short period in hospital. “I’m doing probably two or three gigs a month. I did a gig in Worthing with Dave Quincy last night and I’m knackered. I wasn’t at my good standard because I was still suffering from this illness and in the second set I was running out of steam.

“I enjoyed it, but the journey home in the rain was a bloody nightmare and I thought to myself ‘I’m not getting any younger. What the fuck am I doing this for?’ It’s fine if you’re working with your own band which I always did before, like with Tony Lee and If and even Zzebra – people you got on with and you had a social band. But a lot of the jazz musicians I knew and used to play with, they’re all dead. I haven’t got anybody to play with.”

If Live At The BBC is released on Repertoire Records REPUK1427